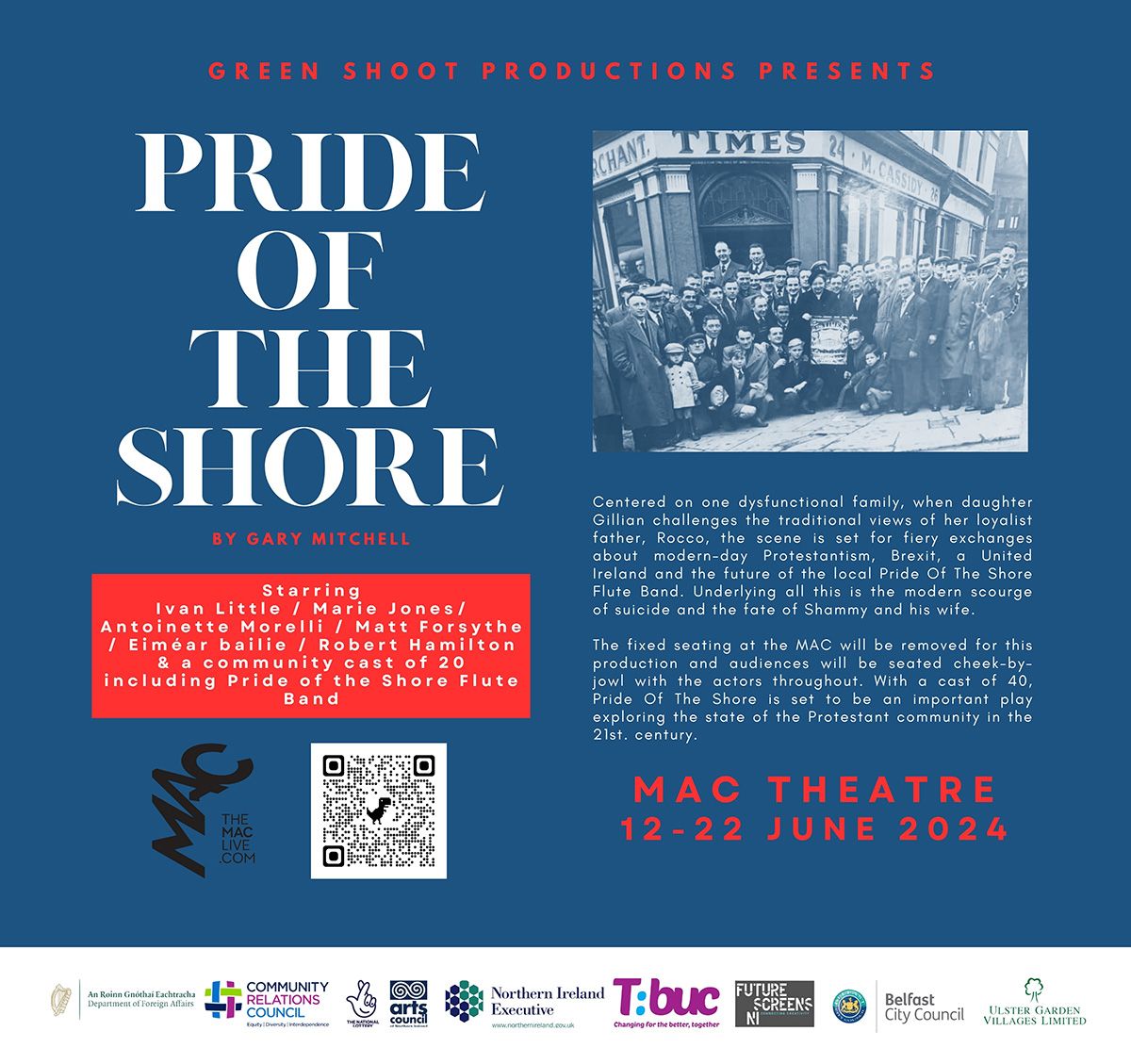

A picture of the perfect day in the perfect place.

Dúlra, right, walks through knee-length grass down at Giant’s Park on Sunday, with the hazy sun low in the sky and Napoleon’s Nose rising nonchalantly from atop the Belfast Hills.

He gets a special pass to visit this off-limits council land thanks to his mate who is assessing birdlife here. And by God, this guy has his hands full because the place is jam-packed with birds.

This oasis is a giant living organism the like of which Dúlra has never experienced. The most incredible thing about it is that it’s in the heart of downtown Belfast – and represents proof that nature will embrace absolutely anywhere as long as it is given the space and freedom to do so. Wildlife isn’t the preserve of the countryside.

Dúlra’s bird expert mate calls it the Serengeti after the African region famous for its wildlife, and he’s not far wrong. And this photograph – of Dúlra almost lost in a swaying sea of grass, with barely a house visible across the expanse of Belfast to the hills – is one to treasure.

Harder than spot the ball... spot the butterflies. Seisear acu ar na bláthanna seo sa ghairdín inniu. One (top right) all the way from Africa too pic.twitter.com/bTy1IhBysw

— Gearóid Ó Muilleoir (@gerrymucker) September 17, 2020

Our first stop was the waterside itself. Thousands of seabirds and waders were scattered like pebbles across the mudflats at low tide. The now-rare curlew’s call echoed over the lough, while a myriad of smaller birds were at home here, probing the shallow water for sealife. Dúlra – his expertise honed on the Belfast hills – would need a book to identify them all. But one bird stood out for its sheer brilliance.

The little egret was as bright as the snow. Like a mini-heron, it was like an ornament beside the mostly brown waders. Dúlra scanned the vast swathes of birds and spotted five in total. This bird once lived all around our coast, but was hunted to extinction for its feathers. Saved from global extinction in its last refuge in the Mediterranean a century ago, it returned to Ireland to breed in 1997, and is now in the process of reclaiming all its former haunts, including Belfast Lough.

The variety of habitats on this site is stunning. Turn in from the lough and you are in thick grassland where birds can live with no disturbance from people or dogs. Three snipe took to the air from our feet from grass in the foreground of this picture that had grown since the terrible fire in early July.

Tall rushes mark sodden patches where sedge warblers were singing. Stonechats called from the odd scattered bush and the whole time we walked, swallows skimmed the grass, sometimes coming right for our faces before veering off-course. It was a spectacular air show.

The most impressive sight of all was in front of us. The grass ahead seemed to come alive against the shimmering sun. Dúlra focused the binoculars on a flock of goldfinches feeding on thistle heads, their flickering wings translucent against the sun. Goldfinches feed on sunflower seeds in many of our gardens, but this is their natural state, balancing on a bending stem, down-like seed heads scattering all around them.

Five minutes later and we were in another habitat – the forest. A thick strip of trees border the M2 here and buzzards, clamhán in Irish, have made it their own. Two birds clashed right above us – perhaps a parent trying to force a young bird to find territory of its own. Rabbits darted in front of us too – the perfect food for these great birds.

The reclaimed land the size of more than 100 football fields at Giant’s Park is among the most valuable in the city. Next year it’s expected that the mountain of trash underfoot will have finally expelled its dangerous gases and it will be safe to build on.

It’s like a feeding frenzy as developers make their pitches for this land. First it was to be a cinema entertainment complex, then an adventure park – even a horse track has been muted. All these would be great additions to Belfast. But between the initial plans for the site and today, it’s clear that something has radically changed. Unintentionally, the Giant’s Park represents the first break given to nature in this city for at least a century.

Can we really just expel nature at a time when the world is walking up to a wildlife and environmental crisis?

Environmentalists – using data from, for example, the bird surveys – are making their pitch too. But it’ll take a brave city councillor to resist the pressure of big business. Politicians don’t get praised for deciding to do nothing. Maybe our councillors should be taken on a guided tour of the wilds of Giant’s Park on a sun-lit September evening. It knocks any wide-screen cinema out of the park.

SWITCHING GEARS: Former top civil servant David Sterling (third from left) stepped down from his post at the end of August and is set to join Ulster Wildlife as a trustee and board member. One of his first visits to Ulster Wildlife preserves was to the Bog Meadow in West Belfast where he met up with Máirtín Ó Muilleoir of the Belfast Media Group and Aidan Crean (second from left), birder and long-term advocate for the bogs as well as Andy Crory and Jennifer Fulton of Ulster Wildlife

* If you’ve seen or photographed anything interesting, or have any nature questions, you can text Dúlra on 07801 414804.