IN February 2014 a well-known secret of our peace process became the subject of public scrutiny.

The ‘On the Run’ letters became a matter of debate as the prosecution of John Downey failed. The process, begun in 2002 during the tenure of Tony Blair, was quite convoluted and had many ins and outs as it developed, culminating in the Supreme Court judgment that these “letters of comfort” were in fact of little material benefit to anyone who had them, as then First Minister Peter Robinson described, “stuffed in their pockets”.

Whatever the limited benefit to the very few people who received them, they have had an impact on the debate on dealing with the past.

The so-called OTR letters were indicative of how our peace process has put the asks and needs of those who participated in it ahead of the rights of victims and survivors. The RUC community in particular benefitted from extraordinary attention: gratuity payments, pay-off schemes, medals and all-round recognition and individualised fiscal benefit. The UDR/RIR similarly. This was a deliberate rendering invisible of state violations whilst families were simultaneously seeking processes of truth, justice and acknowledgement.

Not only was it not in any way shape or form an amnesty, it has zero to do with systemic investigative failures or the protection of state handlers, agents and policy makers. But considered public debate is nigh-on impossible.

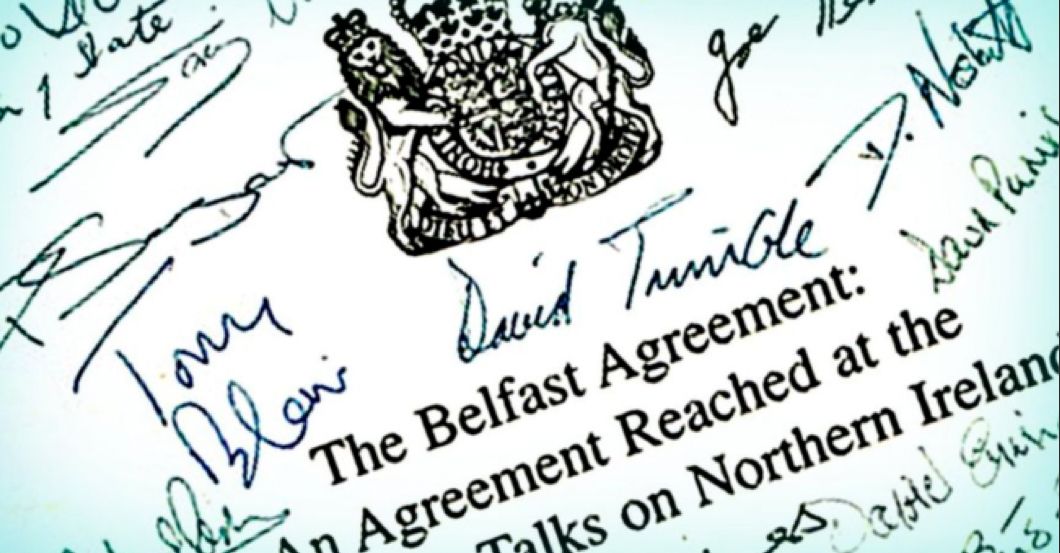

The Good Friday Agreement made provision for those being held in the prisons. Dealing with political prisoners was absolutely vital to confidence in the peace process, and did not go far enough in securing the long-term well-being of those who served political sentences. Systemic discrimination accompanied early releases, an unresolved experience which has not affected state actors as they benefit from impunity. However, there is no doubt that many victims and survivors of non-state actors felt, and indeed still feel, that this was a heavy compromise in favour of the peace process.

How you feel about all of this will be dictated by your narrative of the conflict, a conflict that no-one won. But what is startling has been while there have been attempts to address some concerns of some actors to the conflict there has been a lack of parallel attention or delivery to victims and survivors on fundamental issues of rights. This failure has had a lasting impact on the body politic trying to emerge out of conflict. As we now discuss the way forward on victims rights these limited measures are being abused to a detrimental impact on the resolution of legacy.

If any family tries to challenge state impunity the hollers of “OTR letters!” drown out victims asserting their rights. Whatever the perception of those letters the relatives for those killed by the British Army or RUC had absolutely nothing to do with them.

If families challenge the notion of a generalised amnesty or a partial statute of limitations, they are met with “Ah, but the early release of prisoners was an amnesty.”

Not only was it not in any way shape or form an amnesty, it has zero to do with systemic investigative failures or the protection of state handlers, agents and policy makers. But considered public debate is nigh-on impossible.

Not only was an actor-centric approach wrong as it was an uneven approach to transition, that approach is now in the way of a rational approach to policy making and delivering to victims, even at this late stage.

While we struggle to get past the resulting obstacles and unreasonable hyperbole, there are lessons for other conflict resolution zones in that.