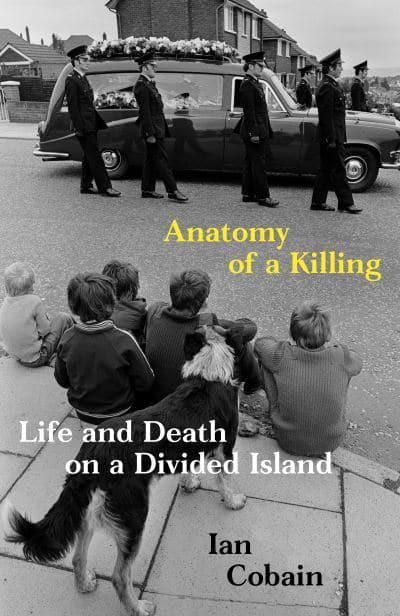

Journalist Ian Cobain decided to go against accepted wisdom when trying to explain the Troubles. Instead of writing a book about the 30 long years of violence, he honed in on a single death.

And by examining in minute detail that one killing, he manages to explain more about the conflict here than most of the vast catalogue of Troubles books that could fill a small library.

It was, in terms of coverage, an insignificant killing - although obviously not for the relatives of the RUC man who was shot and those jailed for it.

The meticulously planned IRA assassination in April 1978 didn’t make many ripples - the 80th RUC officer to be killed in the Troubles was barely mentioned in the English press and even the local media were quick to move on.

In examining the assassination of Constable Miller McAllister in Lisburn, Cobain manages to write a book that’s as compelling as a novel. By focusing on an individual, he humanises history.

TUNNEL VISION: A H-Block parade approaches two British Army Saracens in West Belfast in 1979

Englishman Cobain sets out his stall early. He asks readers not to draw conclusions or get hung up by his varied use of contested language, and indeed he doesn’t seem to agonise over using various terms like ‘the North’ or ‘Northern Ireland’. It’s more important to understand why so many people went to prison than if it should be called the Maze or Long Kesh, he argues.

McAllister’s hobby was racing pigeons, which was to seal his fate. He wrote a column called The Copper in the Pigeon Racing News and Gazette, along with his picture, which was noticed by the IRA.

The British credited it with reducing the number of IRA attacks - but there are no statistics on how many innocent people were jailed as a result of this abuse or how these assaults actually helped exacerbate the Troubles - it was RUC brutality that led the Lenadoon man to join the IRA.

Through pigeons, he got interested in photography, and he joined the RUC Photography Branch, recording scenes of crime.

The book says he’d been ‘dicked’ - spotted - by a republican in Castlereagh, where, as he was in plain clothes, it had been assumed he was an interrogator. A high-priority target.

Once it was discovered he lived in Woodland Park, Lisburn, an Active Service Unit from Andersonstown - formed after a recent reorganisation of the IRA - was tasked to target him.

That unit was led by a Protestant from Tigers Bay - who had the loyalist tattoos on his arms to prove it. He had married a Catholic and they were forced to flee from the UVF, settling in Lenadoon.

WARM WELCOME

He tells the author how he was impressed by the warm welcome he received in west Belfast and never encountered any bigotry or hostility. He gradually got involved in the IRA, storing weapons - but was soon caught. The beating he got in Castlereagh made up his mind - as soon as he was freed he joined the IRA.

Coburn says the RUC tactic of assaulting and beating ‘confessions’ from suspects was backed by the highest echelons in the British government. These confessions would then be put before Diplock courts - it was a conveyor belt straight to the H-Blocks.

RUC brutality of suspects wasn’t occasional. In 1976, 384 people complained of assault, and that rose in 1977 to 671 complaints. Countless others were too afraid to make an official complaint.

As the book points out, it was beyond dispute that suspects were being assaulted - punched, hurled around interview rooms, water-boarded, deprived of sleep, arms and fingers stretched out of shape. The interrogators themselves admitted it years later - one officer’s speciality was ‘hyper-flexing’ - the twisting of joints.

The British credited it with reducing the number of IRA attacks - but there are no statistics on how many innocent people were jailed as a result of this abuse or how these assaults actually helped exacerbate the Troubles - it was RUC brutality that led the Lenadoon man to join the IRA.

Two previous IRA actions spanning 60 years had, reportedly, a direct bearing on the decision to target McAllister. The killing of 12 civilians in a firebomb attack on La Mon House hotel in February 1978 led to a backlash even among republican supporters, and IRA units were instructed to carry out what the British army called CQA - close-quarter assassinations - to avoid the risk of civilian casualties.

The second factor was the assassination of RIC Inspector Oswald Swanzy in 1920, which was ordered by Michael Collins after Swanzy was involved in the shooting of Cork Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtáin. Swanzy was the last member of the Crown forces to be killed in Lisburn.

The Swanzy killing sparked a sectarian pogrom known for decades as The Burnings which led to the destruction of Catholic Lisburn.

The IRA man in Lenadoon tells the author that although Lisburn was only eight or nine miles away, it may have been a thousand. “It was a Citadel,” he says. If the IRA could kill an RUC officer at his home in Lisburn, it would send a powerful message that nowhere was safe.

The author writes: “It was all coming together: the bitter history; the reorganisation of the secret army and its new strategy to strike up close, avoiding unintended casualties; but above all, the determination to kill a member of the security forces in Lisburn and the opportunity to do so.”

Next week marks the 49th anniversary of Bloody Sunday and @MuseumFreeDerry has a full programme of events. 7:30pm Thursday I'll be Zoom-interviewing Ian Cobain about his incredible book "Anatomy of a Killing" about the murder of an RUC man in 1978. Tune inhttps://t.co/6VbnbNlIyW

— aoife moore. (@aoifegracemoore) January 22, 2021

The anti-Catholic pogroms of The Burnings led Cobain to examine the Anti-Poleglass campaign which was at its height at the time of the McAllister killing. He reveals how British forces helped ensure archectecturally designed ‘counter-terrorism’ measures would be build into the very fabric of the new Poleglass estates. Roads and reinforced 10ft-wide pavements were able to bear heavily armoured vehicles, and they had access routes which had fields of fire. The British army even suggested pubs be built there, so as to reduce the demand for republican social clubs.

FRANKLY SHOCKING

And he uncovers the frankly shocking activities of a Security Committee on Housing which was established in 1977, where Catholics/nationalists were discussed as if they were a problem to be dealt with rather than fellow-citizens.

It was attended by the top echelons of the 'security services' - town planners sat with Jack Hermon, then deputy RUC chief constable, and a British army lieutenant colonel. Among the proposals were that Protestant and Catholic areas be divided by motorways and railway lines - something we’re living with today.

One official expresses concern that Catholics are moving into homes along the main routes into Belfast from the north and the south, most likely the Antrim and Lisburn Roads. “If we reach the situation in which… approaches to Belfast are ‘in Catholic hands’... are we not increasing the risk that in any future period of violence, access to the city-centre and major industrial areas will be prone to control by republican extremists?”

Hermon told one meeting that he was worried that if middle-class Catholics moved into an area, they would attract working-class Catholics in their wake - and no doubt open the door to the IRA.

The NIO’s secret defensive planning committee would eventually base staff at RUC stations, with the power to review all planning proposals for housing, health, education, social services and roads. It’s little wonder communities today find it so difficult to rise above sectarianism when it has been permanently woven into their lives by British authorities.

NEW BEGINNINGS: The Poleglass estate under construction in September 1980. Unionists opposed the development with Lisburn councillors threatening not to collect bins in the area.

The assassination of McAllister by a lone IRA man is described in forensic detail. After the shooting, the gun is passed to 27-year-old Brian Maguire at his home in Lisburn, according to the book.

But it soon emerges that the operation had been compromised. The IRA had a spying operation of their own, and they heard undercover British soldiers who were tailing the IRA team.

Before long, four men and a woman found themselves facing the horrors of Castlereagh.

One man had been questioned there before, the author writes, but he was still shocked at what happened to him. “Two detectives shouted at me: ‘If you don’t make a statement, we will send in the hoods’. Five other detectives arrived.

“A detective grabbed me by the right leg, another by the left leg, another by the left arm and another by the right arm. Whilst I was held in this position, I was grabbed by the privates and by the throat and was raised off the ground and thrown over the table a few times.

TIED AND CHOKED

“I was stretched across the table and a detective would press down on my shoulders whilst another would press down on my arms. My arms and legs were pinned down and a coloured towel was put over my head obstructing my vision. They tied the towel around my neck and choked me.

“Whilst this towel was tied around my face, a cup of water was poured down my throat and nose giving me a drowning feeling.

“I remember thinking, how far are they going to go? Are they going to kill me?”

The RUC said they found Brian Maguire dead in his cell, hanging from a torn bedsheet tied to a ventilator grille.

Writing the Troubles - how far should we intrude? https://t.co/0fcbpmXXh3

— Ian Cobain (@IanCobain) February 10, 2021

None of the other republicans would accept Brian had hanged himself. One tells the author: “They went too far and killed him. You couldn’t get your little finger into that grille. You certainly couldn’t get a bedsheet into it.”

The author reveals that one loyalist who had been held in a cell opposite Brian later told a court that on the morning Brian died, a detective had asked what he thought of ‘their handiwork’. He said the officer told him they had ‘got him’ because he had killed a fellow policeman, adding that they could get away with anything at Castlereagh.

The book catches up with the republicans after their release, detailing the problems ex-prisoners face finding work. And Cobain points out that post-Troubles, being politically motivated did not protect republcan ex-prisoners from substantial and complex emotional pressures.

By focusing on a single killing, this powerful, intricately researched book sheds new light on a plethora of issues that fueled the Troubles. It will help a new generation understand the causes of political conflict here, and for that Ian Cobain should be congratulated.

Anatomy of a Killing: Life and Death on a Divided Island. Ian Cobain. Blackwell's. £18.99.

This book was also reviewed by Paul Larkin for belfastmedia.com and can be read here.