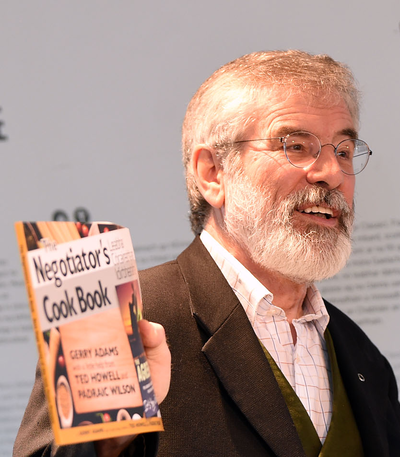

Gerry Adams is the pre-eminent republican activist of our times. A former President of Sinn Féin, he served as MP for West Belfast and as a TD in the Dáil over a four-decade period of frontline elected politics.

He is the author of several books including Before the Dawn, The Street and Other Stories and Falls Memories. His latest collection of short stories The Witness Trees will be published in the autumn.

He describes himself as "an optimistic and hopeful activist" and publishes a famed Twitter account.

LAST week marked 50 years since the death of Frank Stagg on hunger strike in Wakefield Prison in England. Events, including a black flag vigil and a march and rally, were organised to remember the Mayo man. Gerry Kelly, who was on hunger strike in England in the 1970s for over 206 days, during which he was force-fed 167 times, gave the main oration in Ballina and spoke of Frank’s great courage and commitment.

AS I write this column the future of Keir Starmer as British Prime Minister is a topic of conversation because of his mishandling of the Peter Mandelson affair. I know nothing about the ongoing scandal around Jeffrey Epstein other than what I read or see in the media. But the evidence of his serial abuse of young women going back many years is plain to see. My heart goes out to the victims and survivors of this despicable cabal.

IN May 2022 a civil case was launched against me in England. The civil trial will begin on March 9 in London and conclude on St Patrick’s Day.

FOR decades now I have argued that self-determination is one of the big issues of our time. In 2005 I wrote: “In my view the big international struggle of our time is to assert democratic control by people over the decisions which affect their lives. This does not mean retreating behind existing borders and refusing contact with the outside world, but it does mean reasserting the primacy of democracy and working together in order to pursue this objective.”

I RECENTLY came across the autobiography of British General Sir Frank Kitson which was published last year, shortly after his death. It is titled ‘Intelligent Warfare’, an oxymoron in any language. In truth, it is an account of British military failures through several colonial wars in which Kitson fought, including in Ireland. It is also a reflection of Kitson’s enormous personal ego.

ON July 1 the Irish government will assume the Presidency of the Council of the European Union. This will be its eighth time holding this key administrative and political role within the EU and the first time since Brexit.

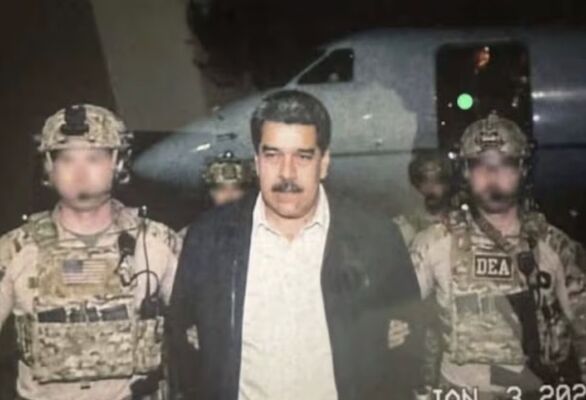

SHOULD we be surprised by the decision of President Donald Trump to kidnap President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores? Should we be shocked by his claim that the US will now administer Venezuela or that US oil companies will manage Venezuela’s huge oil reserves? And what of his threats against Cuba, Colombia, Mexico, Greenland, Nigeria and others?

THE story of Christmas and the birth of Jesus in a stable, as Mary and Joseph sought shelter, is known by billions around the world – even by those of other faiths and none. Christmas will be celebrated, presents given, and many will go to their respective places of worship to remember the child born in poverty, surrounded by a loving family and animals.

THE Kenova Report adds further substance to the litany of existing reports that over several decades have exposed the extent of British state participation in the murder of citizens.

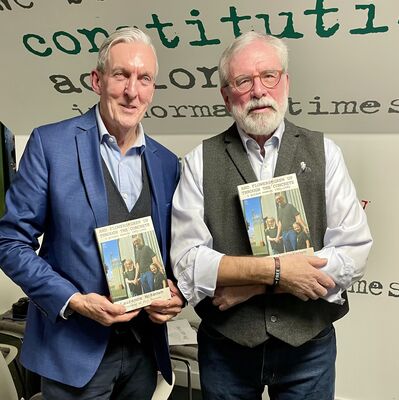

‘AND Flowers Grew up Through the Concrete’ is Laurence McKeown’s second prison memoir. Big Laurny is a very fine writer. This latest book is an account of his journey through imprisonment, hunger strike, brutality and growing self-awareness. It is beautifully written and unashamedly honest in its emotion.

I WANT to respectfully reach out to my unionist neighbours at this time of ongoing change on our island and continuous turbulence and conflict in parts of our world. We should count our blessings. Imperfect though it might be, we have peace and the ability to work out our difficulties peacefully.

FOR the first time ever the families of many of the 207 republican internees held on the Al Rawdah prison ship between 1940 and 1941 met in Belfast. 85 years after their loved ones were interned on the prison hulk the families came together for the launch of Tom Hartley’s insightful account of that period, 'The SS Al Rawdah'.

PHILOMENA Mulvenna died in the early hours of last Friday morning. I have known Philomena and her husband Paddy for most of my adult life. Paddy and she were 72 years married, they had seven children: Colette, Teresa, Brendan, Michael, Desmond, Patrick and baby Martin, who died in his infancy.

MICHELLE O’Neill honoured her commitment to be a First Minister for All when she chose to take part in Sunday’s Remembrance Day ceremony in Belfast. Deputy First Minister Emma Little Pengelly chose not to honour her responsibilities by refusing to attend this week’s inauguration of Catherine Connolly as the 10th Uachtarán na hÉireann. The two choices taken by both leaders highlight again the refusal by unionism to accept the core principles of equality and parity of esteem which are at the heart of the Good Friday Agreement.

COMHGHAIRDEAS to all of those who helped make Oireachtas na Samhna the huge success it was. Thousands of Irish language speakers from across the island of Ireland spent last week enjoying the music, dance, culture, arts, craic and discussions that are part of the oldest Irish language and arts event on the island of Ireland. The Waterfront Hall and other venues were filled with the very young to the not so young Gaels, all actively and enthusiastically enjoying the enormous diversity of Oireachtas na Samhna. Many took part in competitions, including sean-nós singing, sean-nós step dancing and lúibíní (poetic verses).