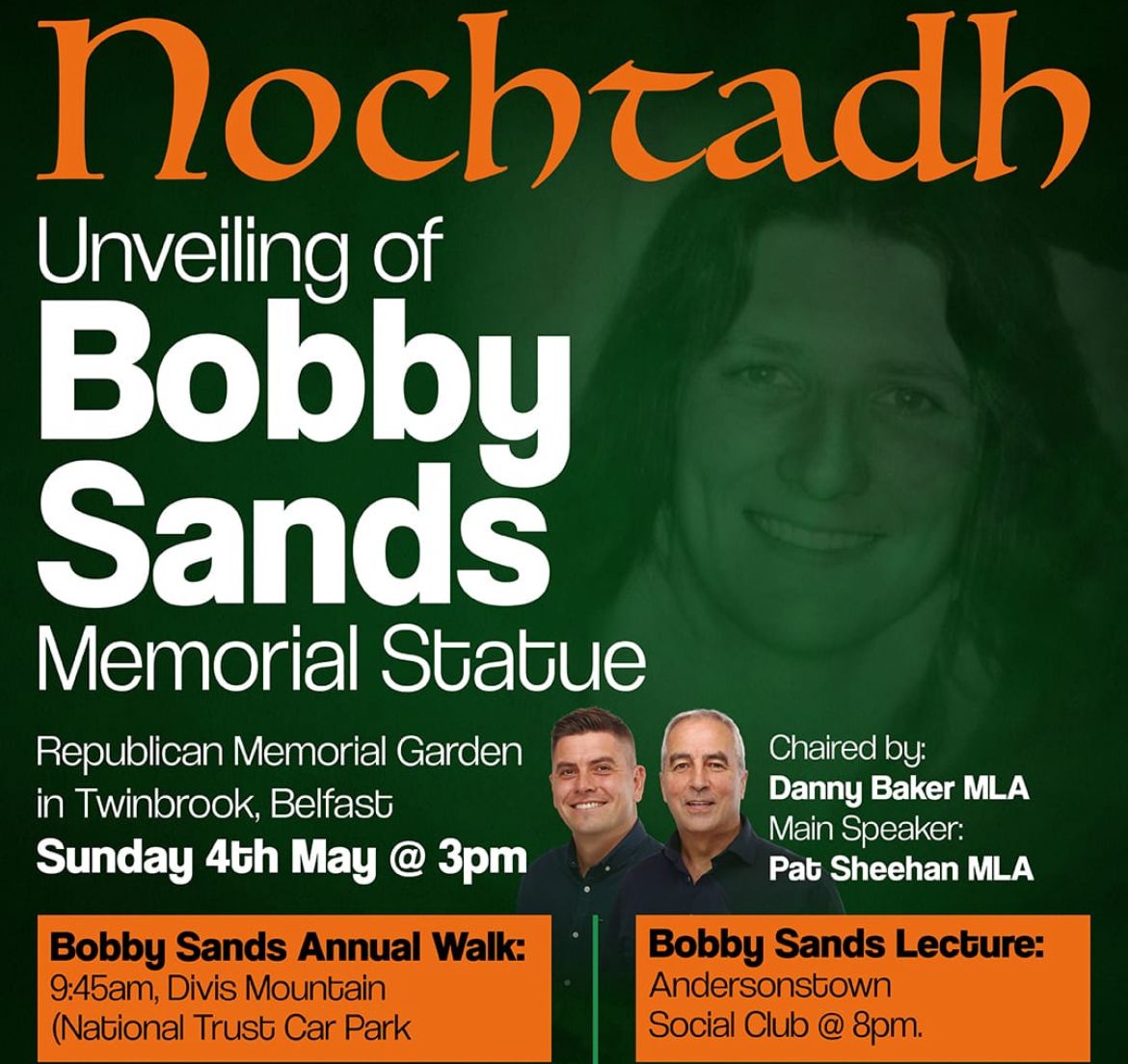

ON May 4 at 3pm, a statue of Bobby Sands will be unveiled in the Republican Memorial Garden, in Twinbrook, where Bobby lived. The organisers of the event, all local republican activists and all inspired by the courage and self-sacrifice of Bobby and his comrades, have worked hard over recent years to raise the funds for the statue. Former hunger striker Pat Sheehan, who spent 55 days on the 1981 hunger strike, will speak about Bobby and his comrades who died.

There will also be a Bobby Sands Mountain Walk that morning and the annual Bobby Sands lecture will be given that evening by Pat Sheehan in the Andersonstown Social Club.

Bobby was the first of ten republican hunger strikers to die during the H-Block hunger strike of 1981. He died on May 5. The others were Francis Hughes; Raymond McCreesh; Patsy O’Hara; Joe McDonnell; Kieran Doherty TD; Kevin Lynch; Martin Hurson; Tom McElwee; and Mickey Devine. Nor should we forget Michael Gaughan, 1974, and Frank Stagg, 1976, who died on hunger strike in prisons in England.

I knew Bobby and Francie Hughes, Kieran Doherty and Joe McDonnell. I also met Tom McElwee and Mickey Devine on a visit to the prison hospital in July 1981. They were all ordinary young working class men. Joe McDonnell at 30 was the eldest. The rest were all in their 20s. In extraordinary times they revealed a depth of resolve that few are ever called upon to demonstrate.

I first met Bobby in Cage 11 of Long Kesh. It was almost certainly at one of the political discussion groups I set up. One of the Nissen huts was a Gaeltacht where those, like Bobby, who wished to live through the medium of the Irish language resided.

Bobby was very interested in the political debates and discussions and became an avid reader of the books which we got from old Joe Clarke’s Book Bureau in Dublin and from the Connolly Association in London. The prison regime banned political books from coming in, but as ever, we and our friends and family outside rose to the challenge and replaced the covers with more innocuous titles. The screws tended to ignore the books of Zane Grey and other western writers.

Bobby was also big into sport. There were two all-weather pitches where prisoners could play football or soccer or simply go out for a run. Running around the pitch was better than the relatively small Cages.

I got to know Bobby well during that time. He was an intelligent, committed republican who was open to new ideas. Many of our discussions focused on how we could turn passive support into activism. He also instinctively understood the need for strategies and for a greater focus on political activism – of building and using political strength. It was at this time that Bobby picked up on the concept of everyone having a role in the struggle, no matter how small. He had a deep interest in international struggles.

Unbeknownst to us, our struggle attracted similar interest in Latin America, in the Palestinian refugee camps, the South African townships and in the front line training camps of uMkhonto weSizwe – Spear of the Nation – where ANC activists were training for operations against the apartheid South African regime.

Bobby was to become a historic figure for ANC activists, including Nelson ‘Madiba’ Mandela. Madiba was on Robben Island when Bobby died. In his cell, in common with all political prisoners, he was allowed as a privilege a calendar on which he marked significant events. On May 5, 1981, a simple, single line is written: ‘IRA martyr Bobby Sands dies.’: a tribute, handwritten on a paper calendar on a cell wall in South Africa which recognised the bond between those of us engaged in freedom struggles.

Bobby was also a writer, a poet, and a musician and writer of songs. Bobby wrote about the horrors of the H-Blocks. His smuggled comms were letters; poems; songs articles; and creative pieces about the brutal reality of life for political prisoners and of British rule.

Bobby spent one third of his 27 years in prisons. He was never interviewed on television or radio and yet his name is known and honoured around the world.

His writings tell us much about the man. His poem, The Refugees, is appropriate in the context of the ongoing genocide in the West Bank and Gaza and the anti-refugee feelings being engendered by right wing elements in our own country, particularly in Dublin. Bobby’s poem is about the events of August 1969 when thousands became refugees as a result of the unionist pogrom.

The Refugees

A hurried worried people, a human stampede to God knows where,

Were spat out from the back streets, for God knows who to care.

Their little kitchen houses lit up the night around about

‘For God and Ulster’ was the reason that the refugees were driven out.

Oh little humble homes where the people hugged the open fire,

Oil-clothed floors and little ornamented cabinets that the neighbours would admire,

The little backyard havens where the youngsters would play

And in the hall the little font of holy water to bless you on your way!

They were little narrow streets where the door was never closed,

Where the characters and folklore were born and not composed,

And where, by the street lamp by the corner, the children made a swing

In a concrete jungle where the hoker was the king.

Oh a kindly people, too clannish were they not,

A simple cup of tea or the milkman’s price, were things that weren’t forgot,

And when there was trouble sure didn’t all of them muck in,

Wouldn’t every man amongst them go out and get stuck in.

Ah sure some returned; others? God knows where they’ve gone,

Driven out in terror by that bigoted orange throng.

’Tis well I recall those hurried worried people, their little mansions burnt down,

As I watched them go in their thousands on the road to Gormanstown.

Pope Francis showed courageous solidarity with the people of Gaza

THE funeral on Saturday of Pope Francis was an occasion to mourn the passing of a leader who championed progressive causes and stood up for those most marginalised and vulnerable while opening the door to reform within the Church.

There is much more to be done to make the Church democratic. I am among those who are alienated by the deep absence of equality in the Church’s structures. Banning women from the priesthood is totally unacceptable as is the opulence of some institutions and the unaccountability of church leaders, particularly over the treatment of children and vulnerable people. But still there are good priests and nuns and many decent people doing their best to make amends.

They include Pope Francis. The many stories of his deep sense of compassion for the sick and vulnerable and those who are victim of abuse and violence have filled the airwaves and social media since his death. His loss is a huge blow to the institutional Church, which often seems aloof to the trials and tribulations of ordinary people while being less than open about the sins of some within its own ranks.

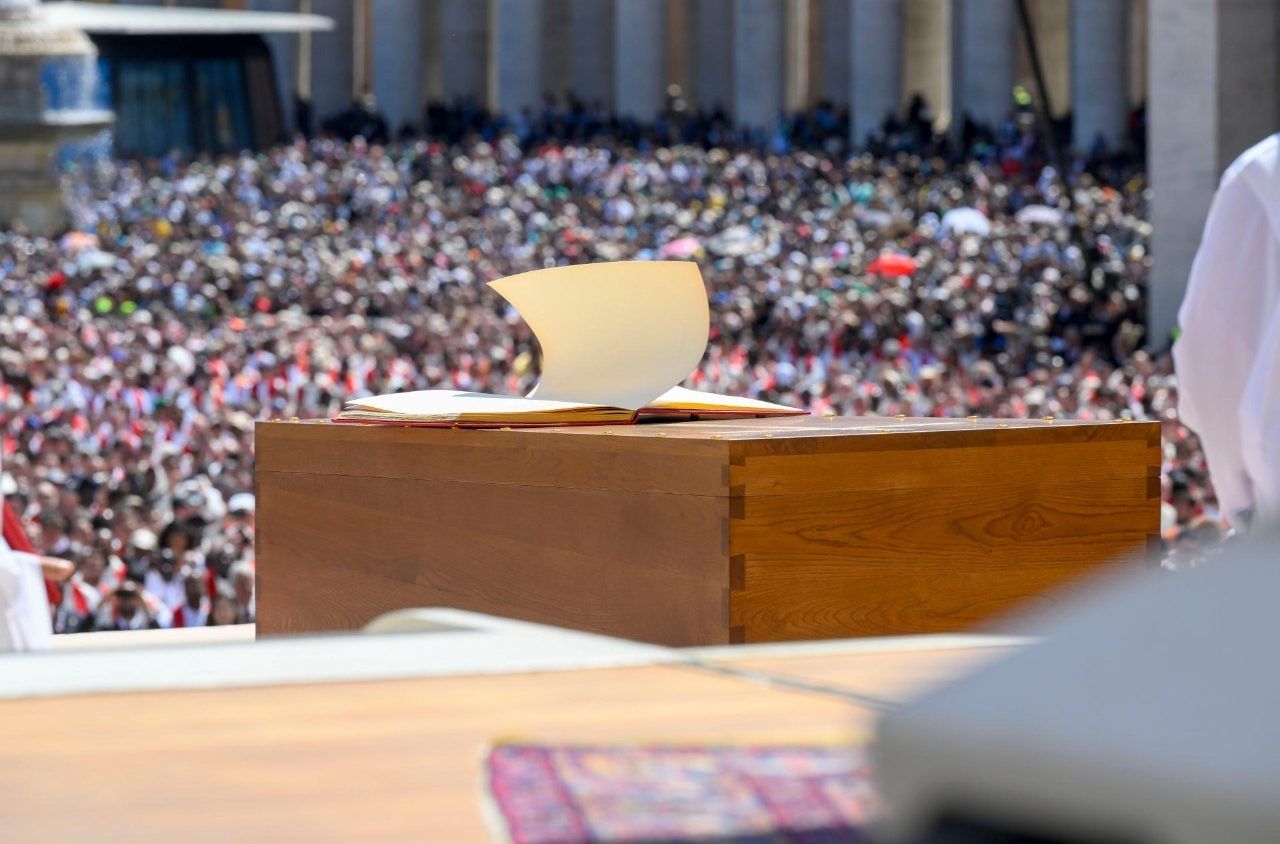

MOURNING: Pope Francis’s simply coffin (Vatican Media)

In his 12 years as leader of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis frequently spoke out against inequality, injustice, climate injustice and militarism, and he was especially vocal in his rejection of those who scapegoat migrants and erect barriers to them. “Migrants and refugees are not pawns on the chessboard of humanity,” he told the Vatican's World Day of Migrants and Refugees in 2013, “they are children, women and men who leave or are forced to leave their homes for various reasons, who share a legitimate desire for knowing and having, but above all for being more.”

But it was his unstinting solidarity with the people of Palestine that will mark out the last years of his Papacy. For almost 18 months following Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip the Pope phoned the Holy Family Church every evening to speak to those who sheltered there. He continued to do so even when he was in hospital.

On Easter Sunday, in his last public remarks, Pope Francis condemned the “deplorable humanitarian situation” in Gaza. He urged Israel and Hamas to “call for a ceasefire, release the hostages and come to the aid of a starving people that aspires to a future of peace.”

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam dílis