20 YEARS ago on Monday one of the most historic and transformative events in the Irish peace process took place. On July 28, 2005, the IRA issued a statement which ended its decades long armed struggle. In its statement the IRA said: “The leadership of Óglaigh na hÉireann has formally ordered an end to the armed campaign. This will take effect from 4pm this afternoon. All IRA units have been ordered to dump arms. All Volunteers have been instructed to assist the development of purely political and democratic programmes through exclusively peaceful means. Volunteers must not engage in any other activities whatsoever.”

The IRA leadership also said that it had authorised its representative to engage with the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning to “complete the process to verifiably put its arms beyond use in a way which will further enhance public confidence.” This was confirmed two months later on September 26 by the Commission.

The IRA initiative opened up opportunities for progress.

Peace processes are by their very nature challenging and difficult. They frequently fail. Many of the wars of the 1960s and 70s were a response to the colonial occupation and exploitation of native peoples by colonial powers. Africa saw many examples of these.

Some conflicts went on into the 1980s and 90s. Algeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia), Angola, Mozambique, and others, including in Asia the Vietnam War and in the Middle East the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories. The South African peace process brought an end to apartheid and witnessed the election of Nelson Mandela as President of that country in 1994. In our own place, our peace process brought an end to decades of conflict and heralded processes of change.

Today, in a world still bedevilled by wars, the Irish peace process is frequently held up internationally as an example of a peace process that is working. The governments occasionally try to root it in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985. But the truth is that it started in the 1970s when republicans began to claim back the word ‘Peace.’

The moves made by the British government, endorsed by the Irish government, from 1970 until the mid-1990s, all failed because they were primarily about defending the status quo, placating political unionism and defeating the IRA. None of the serial ‘talks about talks’, or Conventions or Assemblies, or round table talks that ten different British Secretaries of State commenced between 1972 and 1996, made any meaningful progress.

West Belfast event to mark 20th anniversary of end of IRA armed campaign https://t.co/b7DMGKOGg0 via @ATownNews

— Andersonstown News (@ATownNews) July 19, 2025

Why? Because they were partitionist at their core and they excluded elected republican representatives. They were aimed at defeating republicans. And, of course, republicans could not be defeated. But that was not sufficient. Not being defeated was not enough. We had to develop strategies aimed at winning.

This led to a dynamic shift when republicans developed a peace strategy and began to take independent political initiatives that opened up new possibilities. The most important was the IRA cessation in 1994 which Seamus Heaney described at that time: “It created a space in which hope can grow.” He was right.

The 1994 cessation, like the July 2005 announcement, involved no deal or trade-off with the British government. It was the outworking of our efforts to build a viable alternative to conflict. It was a unilateral political initiative taken solely by republicans and involving others here in Ireland and abroad.

Of course, everyone wants peace. But on what terms? For Benjamin Netanyahu peace in the Middle East means the ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip and the creation of a single unified Israeli state, including all of the Palestinian territories. But that would not be peace and all sensible people know that.

For unionists and the British government, peace in Ireland meant peace on their terms. But that also is not feasible.

Most thinking unionists know that the game is up. That there is no going back to the old Orange state. There is evidence that some are even now coming around to the view that being part of the union with Britain, outside of the European Union and on a divided island, is not in their best interests.

There are, of course some who refuse to acknowledge the political, electoral and demographic changes that have and are taking place every day. They continue to fight a rearguard action against the referendums provided for in the Good Friday Agreement, but their political strength is much diminished.

However, they are assisted by the British government. And, sadly, also by the Irish government. But the electoral strength of Sinn Féin today is testimony to our determination and the good sense of our strategic goals.

Republicans long ago understood the need to see negotiations as an area of struggle and that our responsibility, along with others is to persuade as many people as possible that Irish unity is the best outcome for all the people of our island. That means us reaching out to our unionist neighbours, especially those prepared to consider how life might be for them, and us, after the union and after partition.

So, twenty years after the IRA initiative of 2005, the challenge for us is to advocate for the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement and to create the conditions for the holding of the unity referendums. That means pressing for the establishment of Citizens’ Assemblies or Forums in which people can come together in confidence to talk about a new Ireland, what it will look like and what governance and other options are available to us.

Séanna reflects on delivering historic IRA statement 20 years onhttps://t.co/oB4gQJB7IX

— Andersonstown News (@ATownNews) July 25, 2025

It also means that we need a plan for unity. The Irish government carries the greater responsibility for this, but Micheál Martin refuses to develop one. We also need local plans. Wherever you live on the island of Ireland or within the diaspora, if you are a United Irelander you need a unity plan. Unity is not a job of work just for elected representatives. It is for all of us.

We now have the opportunity, not available to previous generations, to win national freedom through peaceful and democratic means. As Bobby Sands said: “If they aren’t able to destroy the desire for freedom, they won’t break you. They won’t break me because the desire for freedom, and the freedom of the Irish people, is in my heart. The day will dawn when all the people of Ireland will have the desire for freedom to show. It is then we’ll see the rising of the moon.”

That will take hard work by all of us, new phases of struggle, of activism and of active campaigning.

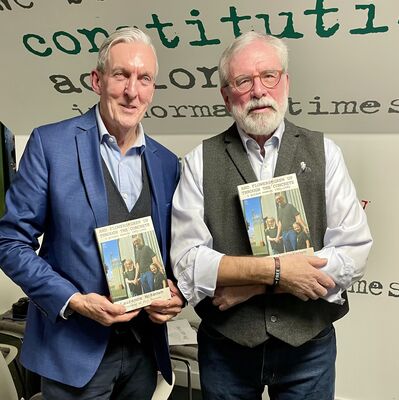

In 2004 the DUP walked away from a possible agreement and the peace process looked for all the world as if it was finished. But republicans stepped up to the mark and this Saturday at 2pm in the Balmoral Hotel a public meeting will be held to discuss the historic 2005 events and their implications, twenty years on, for a new Ireland.

Young vote makes a difference

THE decision announced last week by the British government that it will be lowering the voting age to 16 is a welcome move. There is already widespread support for a reduction in the voting age. Last September the Assembly backed a Sinn Féin motion calling for this change. In the South the policy has received widespread cross-party support from Sinn Féin, Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil, the Green Party, the Labour Party, Social Democrats, People Before Profit and many independents.

The London government is focused on the 2029 Westminster election but the North will have local government and Assembly elections in 2027. The focus now must be on ensuring that the necessary legislative steps are taken to ensure that 16- and 17-year-olds can vote in those elections.

Updating the electoral register and ensuring that this new tranche of young voters have suitable identification will be a big job of work, but with political will it can be done. It would also send entirely the wrong message to future voters if the 2027 deadline is missed.

Legislating for young people to have the right to vote is the right thing to do. All parties in the North, with the exception of the DUP, support changing the voting rules. Young people should have the right to vote on decisions that impact on their lives, including voting for a united Ireland.