Gearóid Ó Muilleoir, pen name Dúlra, is a wildlife buff who was brought up on the slopes of Belfast’s Black Mountain where he spent almost every waking moment hillwalking, birdwatching and fishing.

He’s witnessed massive changes in the local environment, with fields disappearing and nature retreating. “When I was young we had corncrakes breeding in the heart of west Belfast and a barn owl used to swoop down over the street as we played in the evening," he says.

“All that’s gone - but the one thing that has given me heart is the rewilding movement. Nature just needs to be given the space to do its thing without human interference and it can return from the brink.”

Gearóid has spent a lifetime in journalism, working with all the main newspapers here and he’s now production editor of the Sunday World. Outside of the environment, his other passion is the Irish language and he’s a regular on award-winning Belfast station Raidió Failte.

by gearóid ó muilleoir

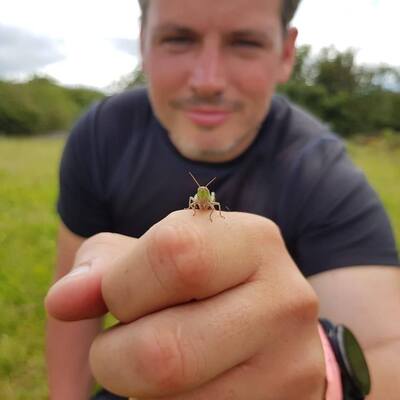

DÚLRA has no doubt which Belfast area is tops for nature. It’s got to be Poleglass – and this week he got further proof of it.

IT'S a special bird that you’ll probably never see – and not just because it’s in decline.

TERESA Girvan’s once-beautiful patio is quite the mess – thanks to a sparrowhawk.

IT’S always a treat to see a blackcap in the garden. Because it’s evidence that in the race to survive, taking a chance can pay off big time.

DÚLRA learned the lesson early in life and it stayed with him ever since – throw out a few handfuls of finch seeds and these colourful birds will be your companion forever.

THERE was something unusual – eerie even – in the air as Dúlra and Squinter dandered along the shores of Lough Neagh on New Year’s Eve. It was a perfect winter’s day, crisp and cloudless. But the fields facing the lough seemed to have rejected the tranquil mood.

IT’S those who have done least to create climate change who suffer the most from its effects – and no-one knows that more than Trócaire’s David O’Hare.

SAVING Lough Neagh isn’t really difficult – we just need to listen to David Kennedy and the other members of Crumlin and District Angling Association.

THESE bees are our finest local residents – because they literally consist of the Best of the West.

DÚLRA finds it impossible to define his feelings when he discovered a dead bird under the kitchen window this week.

CAN you be in the country and the city at the same time? You can – at St James’ Community Farm.

THIS is the exact time that birds most need our help. With winter about to hit, you can save lives.

WATERWORKS gardener Liam Mac Alasdair has just started a course in amateur photography – but he’s already bagged what should be a prize-winner.

DÚLRA wouldn’t have the courage to stand where Jake Mac Siacais is, especially with Halloween round the corner. Because he’s actually inside Ireland’s ‘Gateway to Hell.