A NEW book celebrating the life and work of the Donegal folklore collector Seán Ó hEochaidh will be launched this week.

The story of Irish America’s role in the Troubles is too often told from the perspective of New York or Boston. The Next One Is for You, by Ali Watkins, is a gripping account of how a group of working class Irish-Americans in Philadelphia procured and shipped weapons to the Provisional IRA in the early 1970s.

Miami Showband survivor Stephen Travers’ book The Bass Player – Surviving The Miami Showband Massacre was launched this week. Below is an extract from the book...

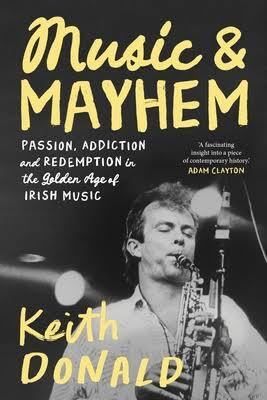

If there's a soundtrack to the tectonic plates of Irish history separating in the bitter Hunger strike year of 1981, it would be Moving Hearts' eponymous album of that momentous year.

'Wild Colonial Boys' by Thomas Paul Burgess, a native of Protestant North Belfast and one-time drummer with punk pioneers Ruefrex, is the best-written of four musical memoirs I have binged on over recent weeks (reviews to follow).

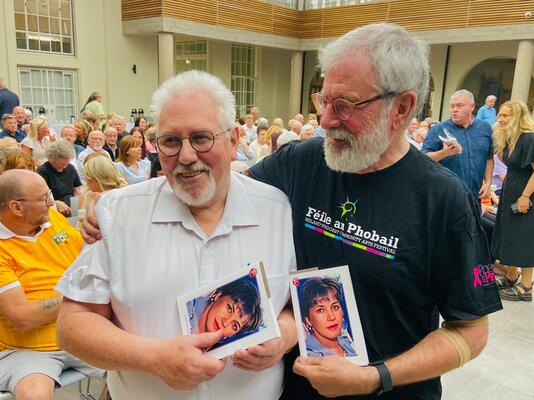

Siobhán O Hanlon – A Sound Woman SIOBHÁN O'Hanlon, had presence. It’s a special quality. It arrives early and evolves, shaped by the circumstances of a life. Leaders can have many qualities which set them out. Not all of them have presence. Siobhán had both. And the power and influence that comes with presence. And she used this influence to good effect wherever her presence was felt.

CAPTAIN Robert Nairac, an undercover British Army officer, was central to organising the 1975 Miami Showband Massacre which killed three members of the group, according to Des Lee, one of surviving band members. In his new memoir, My Saxophone Saved My Life – which is published on the 50th anniversary of the attack – Lee reveals that a British Ministry of Defence documentation that he has seen, as well as his own memories of the paramilitary attack, left him “in no doubt” as to Nairac’s central involvement in the atrocity. Lee believes Nairac was present on the night of the massacre in Buskhill, between Newry and Banbridge, which also left two of the UVF gang dead.

In the classic short story ‘Guests of the Nation’ by Frank O’Connor, the narrator and his fellow soldier have befriended the two British hostages they’re charged with guarding. War of Independence is raging, yet the IRA men play cards with the hostages each night, adopt some of their quirky manners of speech, and debate the existence of God, capitalism, and honor.

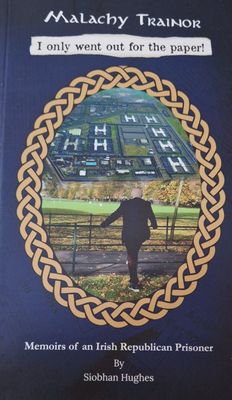

I Only Went Out For The Paper – Memoirs of an Irish Republican Prisoner. By Siobhan Hughes MALACHY Trainor, or Muffles Trainor, was only a name amidst the many men and women prisoners who were on the blanket, no-wash protest in the H-Blocks and Armagh Jail during the 1970s. He feels that their voices are still unheard and has produced his memoir with the writer and researcher Siobhan Hughes. Malachy was from a Catholic family, who originally lived in Lisburn, but their home and business was burnt out in the pogroms of the 1920s. As a consequence they were forced to move to Armagh. Northern Ireland’s Catholic population had lived through marginalised political and social segregation from the predominantly Protestant hierarchy. This was a time of turbulent change in the world’s political and social history. Siobhan gives the reader this historical insight into the lead-up to the Northern Ireland conflict. Malachy in his youth followed the drumbeats of civil discontent of the1960s. His republican baptism came on a day he went out for the newspaper, November 30, 1968. A march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement in Armagh. It was stopped on Ogle Street. It was here that Malachy faced the wrath of Ian Paisley and Ronnie Bunting Senior. Inspired by Bernadette Devlin – his ‘Joan of Arc’ – he joined People’s Democracy, followed by a progression into the INLA. Arrested for possession of arms and explosives in 1976, he served his time in H-Block 5 with Brendan 'the Dark' Hughes. On entering the H-Blocks Malachy joined the blanket protest, which moved on to the no-wash protest as a result of prisoners being beaten up during visits to the washrooms. This protest was also carried out by female republican prisoners in Armagh Gaol. The female role, both politically and from the grass roots, is explored by Siobhan within this memoir. On returning from a prison visit, Malachy endured the brutality of a forced wash at the hands of authorities. Darkie Hughes, a committed republican, was visibly shocked by the physical and mental change in Malachy. Darkie was the Operation Commander of the IRA. Bobby Sands occupied the next cell. Malachy recalls the two men talking through the pipe in Irish. Malachy admits that his own Irish was not good, but “You learnt quickly in prison. It was a code to defeat the screws." Darkie and Bobby hunkered down and discussed starting an inevitable hunger strike. In his memoir Malachy, by his own admission, did not volunteer for the hunger strike as he describes that "he could still smell the sweet scent of cherry blossom". To join the hunger strike was in itself a death sentence.

THE days of journalists being given a week, two weeks, a month, to go off and pursue single stories are virtually at an end. Long-form investigative pieces to all intents and purposes don’t exist any more and as newspapers struggle to come to terms with falling sales and dwindling readerships, the reality of life as a reporter has changed utterly.

THE heartbreaking account of the killing of a West Belfast schoolgirl during the Troubles features in a new book on trauma, as told by her brother.

A NORTH Belfast woman has penned a book of poems about her cancer journey in a bid to raise funds for some of the organisations that have supported her through her illness.

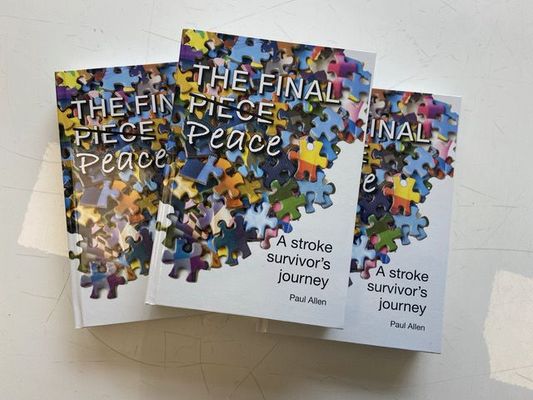

PAUL Allen was the manager of the Wellworth store in the newly built Westwood Shopping Centre when it first opened in 1990. After several years at the helm in Andersonstown where he was a familiar face he moved on and managed the supermarket's store on the Shore Road. Originally from Omagh in County Tyrone, several years ago he survived a stroke, and as it is said that “there is at least one book in all of us” he has put pen to paper and written about his experiences and journey since in a new book ‘The Final Piece Peace’ – A Stroke Survivor's Journey of Discovery. “The Final Piece Peace stems from my personal experiences after suffering an atypical stroke and maybe more importantly it details how I managed to navigate the quagmire that my mind had been reduced to in the months or indeed truthfully the years that have passed post stroke,” he said. “Unfortunately, my stroke was not diagnosed for over four months after it occurred following an initial fall and head trauma.” Paul says that after a stroke there is much relief that you have indeed moved into that group of people who can class themselves as a ‘survivor’ but that comes after the initial shock and the ‘why me?’ syndrome. “At some point I read that one-in-four people over the age of 25 will suffer at least one stroke in their life-time," he said. "Of those ten to 15 per cent don’t make it to hospital and up to 25 per cent more don’t get beyond the first 24 hours. Towards 3,000 people each week in the UK suffer a stroke, that’s 152,000 per year, or to put it another way that equates to one person every five minutes. “Of the survivors only a very small percentage make a complete recovery, the rest of us have untold and often misunderstood brain damage and/or physical impairments. It is said that no two strokes are the same but then again no two people are the same. We all have our own personalities, our own views on the world, never mind many different levels of education. Then we should also consider our own place on any countless number of spectrums that exist. “So, who’s really brave enough to say which of us are normal to start with and indeed who can actually determine what a normal brain or mind is? Therefore, when all things are considered, should we really expect the medical profession to be able to fix the inner workings of each individual working mind? The answer is unfortunately no, it is actually really up to the survivor to rebuild that broken jigsaw themselves.”

A FORMER West Belfast teacher has penned a fascinating new book on the history of teacher training for young Catholic men in the north of Ireland from partition to the present day. Readers may think that ‘Strawberry Hill and Afterwards’ is a strange title for the book, until author Jim O’Hagan explains its significance. Strawberry Hill was the Catholic college in London where in the 1920s young Catholic men from the newly created state of Northern Ireland were sent to be trained as teachers. For those who would later attend St Joseph’s at Trench House the book features many familiar names of lecturers and students from the college’s 30-year history.

MYSTERY surrounds the identity of a West Belfast writer whose collection of short stories has been praised as “exceptional”. ‘Every One Still Here’ has been written under the pseudonym of Liadan Ní Chuinn and is published by Stinging Fly Press. Early versions of some of the stories were first published in The Stinging Fly magazine and in Granta online. This is Liadan’s first book. Liadan Ní Chuinn was born in 1998 and has requested no interviews to publicise the book's launch.