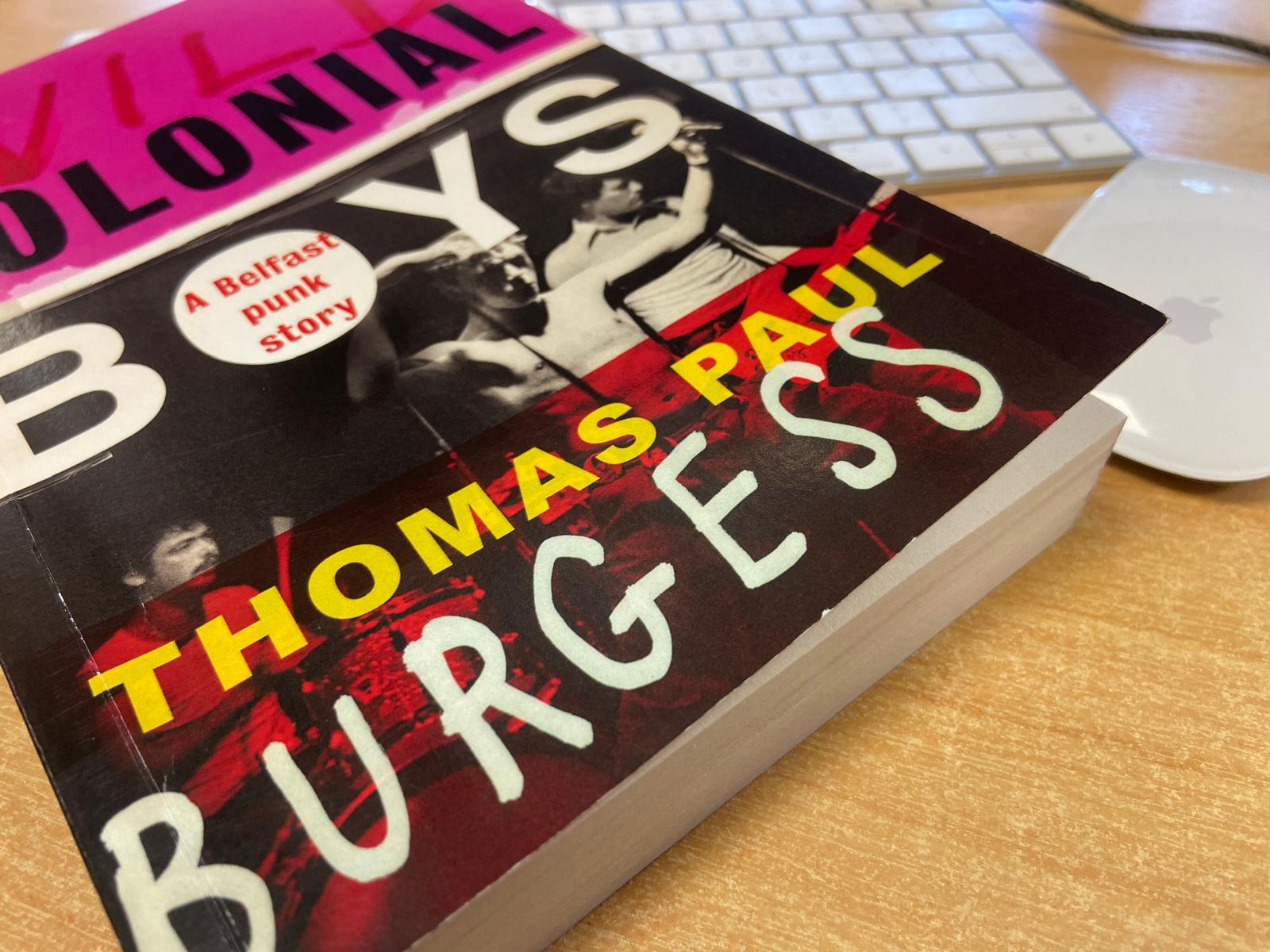

'Wild Colonial Boys' by Thomas Paul Burgess, a native of Protestant North Belfast and one-time drummer with punk pioneers Ruefrex, is the best-written of four musical memoirs I have binged on over recent weeks (reviews to follow).

It is let down, however, by a Cave Hill size chip on the shoulder of the author who surveys the smouldering remnants of his career as punk star and concludes that the world and his mother had it in for him. The culprits? His punk bands peers; Good Vibrations founder and demi-god punk Terri Hooley, the music press, the British Left, the Troops Out movement, smiling Shane McGown and, for good measure, 'Oliver's Army' recruit Elvis Costello.

Fortune, of course, favours the prepared and perhaps Ruefrex were the architects of at least some of their own misfortune. Starting with that terrible moniker.

Ruefrex stormed the Belfast punk scene in the late seventies with a distinctly political offering. Unfortunately, this was neither the 'SS RUC' anarchic politics of The Outcasts from the Shankill nor the socialist call-to-arms of Joe Strummer's 'White Man in Hammersmith Palais'. Rather, it was, when stripped back, life through a unionist establishment or even NIO lens. Nothing wrong with that, of course except that punk rock adherents have always been thin on the ground at DUP conferences and Hillsborough garden parties

Not that this wasn't well-meaning hands-across-the-barricades stuff with Ruefrex backing their oft-blistering performances with efforts to help the nascent integrated school movement. That courageous outreach to the masses culminated in a gig at the Workers Party social club in Turf Lodge. While that won Ruefrex full marks for proselytising, their shot at stardom was hampered by sludgy songs and portentous lyrics.

Stiff Little Fingers had it right: you want to pen a pean to the Peace People and slam the IRA and UDA (but not HMG), hire a Fleet Street hack. Doubling as drummer and songwriter for Ruefrex, Burgess preferred to trust his own political instincts and creative capabilities. All of which climaxed in a long-forgotten single berating Gerry Adams complete with cover-sheet photo of the bearded one and his IRA man alter-ego!

Still, there is much in 'Wild Colonial Boys' to recommend. There is a fast-paced and evocative account of Burgess' youth in bleak seventies Glenbryn which brought him from marching on the Twelfth with the Pride of the Shankill Flute Band to forming the Roofwrecks (later rebranded). Gritty and grim, Belfast of the late seventies emerges mired in sectarianism and clinging to puritanical certainties even as punk assails its ramparts. The scene was set for Ruefrex to be part of Belfast's now-famed punk revolution. If only they hadn't have taken agin their punk peers. Could it really be true that "Rudi and The Outcasts at best tolerated, at worst despised us"? Probably if the author's account of the band's unremitting "arrogance" is to be believed.

When it came to pissing people off, Ruefrex were chart-toppers. Burgess recalls how, despite Ruefrex slagging them off for being unauthentic, punk princes Stiff Little Fingers invited the band to open for them several times. Until that is Ruefrex destroyed the green room before opening for SFL in Dublin's Mansion House. They topped that show of gratitude by leaving for their hotel without staying to watch SLF's set. And one wonders what their Workers Party patrons would have made of their disdain for hotel workers who had to tackle a fire set in a lobby chair by Ruefrex hangers-on before "TC eyed up all the used pint, spirits and wine glasses that had been gathered by the saloon staff and ran the length of the bar sending them all crashing on to the floor. Grinning, he looked, at me for approval. All I could think to say was 'punk rock'."

And while the Band's obnixousness back then can, perhaps, be put down to immaturity, how do we explain the author's predilection for settling old scores almost 50 years later in 'Wild Colonial Boys'?

Terri Hooley's famed Good Vibrations record shop, ground zero for punk rock, was, he tells us, "little more than a youth club". Stiff Little Fingers were one-dimensional. And on pours the bitter commentary. Poor Little Me biography is not a literary genre. There's a reason for that.

The constant complaining in fact only draws the eye away from the real talent and promise of Ruefrex. In its heyday, and with the help of exposure in a 1980 BBC Cross the Line documentary, Ruefrex were winning fans and turning heads with a tight, pulsating sound. There were mentions in the rock Bible NME, a first single, plays on John Peel's immortal late night Radio 1 show and gigs in dingy but hallowed London music venues. Front man (Alan) Clarkey possessed enough charisma and rock 'n' roll chops to (almost) propel Ruefrex to the major leagues. In this telling, Clarkey just didn't have the drive or ambition to make the sacrifices necessary to make it big but perhaps he just tired of Burgess' insufferable carping.

Either way, Ruefrex have a proud legacy. 'Cross the Line' - the peace line, of course - was a high watermark for the North Belfast youngsters. But a punk anthem appealing for a stop to "sectarian murders..committed by young working class men on young working class men" was a dead end in late-seventies/early-eighties Belfast. And more's the pity.

By 1983, Ruefrex's race had been all but run. Band stalwart TC was handing in his cards and Clarkey was clocking out before changing his mind and clocking back in. Single number two was a washout. An invite to record a live session for Dave Fanning at RTÉ flopped — which Burgess blamed on "the archaic nature of a station that still featured tape operators, decked out in white lab coats and armed with clip boards. We were never asked back again."

A 1984 single 'Paid in Kind', which you have never heard of for very good reason, "received little publicity and John Peel would not play it (for whatever reason)" recalls Burgess. Though, true-to-form the author goes on to tell us the reason. The lyrics about a drunken IRA man (I'm not making this up) who shoots a British soldier and a Catholic kid who got in the way "irked the sensibilities of the liberal left at a time when the Troops Out Movement was at its height". That's the same Troops Out Movement which, effectively disowned by the Labour Party had, at its height, a few hundred members and the resources of a Tufty Club.

Ruefrex, even as they came apart at the seams, enjoyed a brief resurgence with 'Wild Colonial Boy'. This number was inspired by none other than NORAID's Martin Galvin (recently the subject of an adulatory doc shown on RTÉ) who was banned from entering the North to address an August 1984 event on the anniversary of internment. When the loquacious Galvin appeared at a rally outside Connolly House on the Andersonstown Road, the RUC, with batons swinging and plastic bullet guns popping, scythed a path through demonstrators who had sat down on the road. Seán Downes was shot in the heart at point blank range by plastic bullet and lost his life.

Taking (in vain) the name of the popular Irish ballad of exile and dispossession, Burgess responded to this police riot by with a song blasting Irish American support for the IRA. To be fair, the Irish American protagonist sending greenbacks to the Hucklebucks on the border wasn't drunk but he was a bigot. From Troops Out to Tropes In.

With Clarkey back on form, the raucous 'Wild Colonial Boy' was cut as a single in a Co Antrim studio where the veteran producer, recalls the author, "took an instant dislike to me". Imagine that.

A methodical organiser and gifted writer, Burgess had an after-life in the London rock scene, enjoying a double page feature in Melody Maker and serving stints as a critic for the music press. Yet, throughout this period, he was, we learn, a bête noire of the all-pervasive Irish republican network which stretched right as far as the editor of the NME! Even the pre-eminent songwriter of the punk era Elvis Costello was on his case. Apparently, he branded the Ruefrex boys "Orange bastards" in order "to bolster his Irish 'rebel' credentials." And as for those "professional Irishmen" the Pogues, less said, soonest mended.

Catching more bees with honey was not the Ruefrex route to success. "I was abrasive and dismissive of the industry I had ached to be part of for so long," confesses Burgess. There was an album and a final flurry but by 1985 Ruefrex was, like a million other could-have-beens who braved the rock 'n' roll waters, sunk.

While the other band members back in Belfast hung up their Lord Anthony jackets, Burgess remained in London. In a welcome surprise for the reader, these closing chapters of the author's time adrift in London are the most moving of this memoir.

And the author's eventual boat home to his native city is a touching and redemptive close to a decade-long adventure. "The rain had stopped, and the clouds broke in one or two places. Early morning shafts of sunlight struggled through...I reached for my Walkman...Clamping the headphones on and pushing against the heavy door with my shoulder, I emerged on deck to be buffeted by the strong winds that swept the channel...It was time."

Oil on troubled waters, hope for the future, the seeds of peace sprouting, the author getting over himself (per the advice of The Cult's lead singer) is a masterful full-stop on what was clearly only the first chapter in Burgess' life journey (which would take him via Oxford to a storied, 30-year career in Cork University).

If only. Ill-advisedly - doesn't anyone employ editors anymore? - the author tacks on a five-page whining 'coda'. The lowpoint of which is an ad hominem attack on the legend that is Terri Hooley. "Terri was not a particularly talented, egalitarian, philanthropic, politicised or entertaining individual" etc. etc.

And as for those other Belfast heroes of the Punk Pantheon: "Bands like The Outcasts, Rudi and yes, even Stiff Little Fingers, may have postured as something radical, they were in fact very liberal indeed. The Outcasts sang songs that were unashamedly misogynistic, while Rudi's lyrics rarely rose above the inane."

There's more digging to be done: "Ruefrex were consigned to the margins (in the Good Vibrations movie) and those prejudices endure to the present day. Given the band's second-time-around success, it is likely that Ruefrex have easily outsold both the Outcasts and Rudi internationally."

Emm! Let's ask Spotify. Rudi's classic 'Big Time' has been played 664,000 times. The Outcasts' calling card 'Just Another Teenage Rebel' has earned 225,000 spins. Stiff Little Fingers' 'Suspect Device', the work of lead singer Jake Burns and not a Daily Mail journo, has been pogoed 14 million times.

'Wild Colonial Boy' has been listened to 17,000 times, which is hardly the stuff of Rock 'N' Roll Hall of Fame bragging rights.

Ultimately the only person standing between the wonderfully talented Thomas Paul Burgess and fame – both then and now — is Thomas Paul Burgess.

Wild Colonial Boys. Thomas Paul Burgess. Manchester University Press. Available at No Alibis bookshop, Botanic Avenue.