There's a brief scene in Poleglass author Michael Magee's excellent debut novel 'Close to Home' where its working-class West Belfast narrator, previously sympathetic to the well-meaning statements of a BT9 interlocutor, reacts scornfully in the next second to the latter's casual deployment of 'Northern Ireland' during their interaction.

The scene is played for bittersweet laughs, yet captures in microcosm that cultural chasm which remains, almost thirty years on from the Good Friday Agreement, between the official arts and media institutions of "Northern Ireland", bunkered in their south and central Belfast redoubts, and their working class, mainly nationalist, hinterlands of Belfast and Derry that supply their most successful authors, playwrights, musicians, and comedians; Magee among them.

It's a distance of politics, class, language, and religion, all at the same time, premised primarily on the radically antithetical ways in which the quarter-century conflict that scarred the North after August 1969 was lived, and today remembered: on one side an official narrative of warring sectarian tribes, adopted wholesale by the indigenous liberal middle classes, juxtaposed to the grinding suffering visited upon working class nationalist communities.

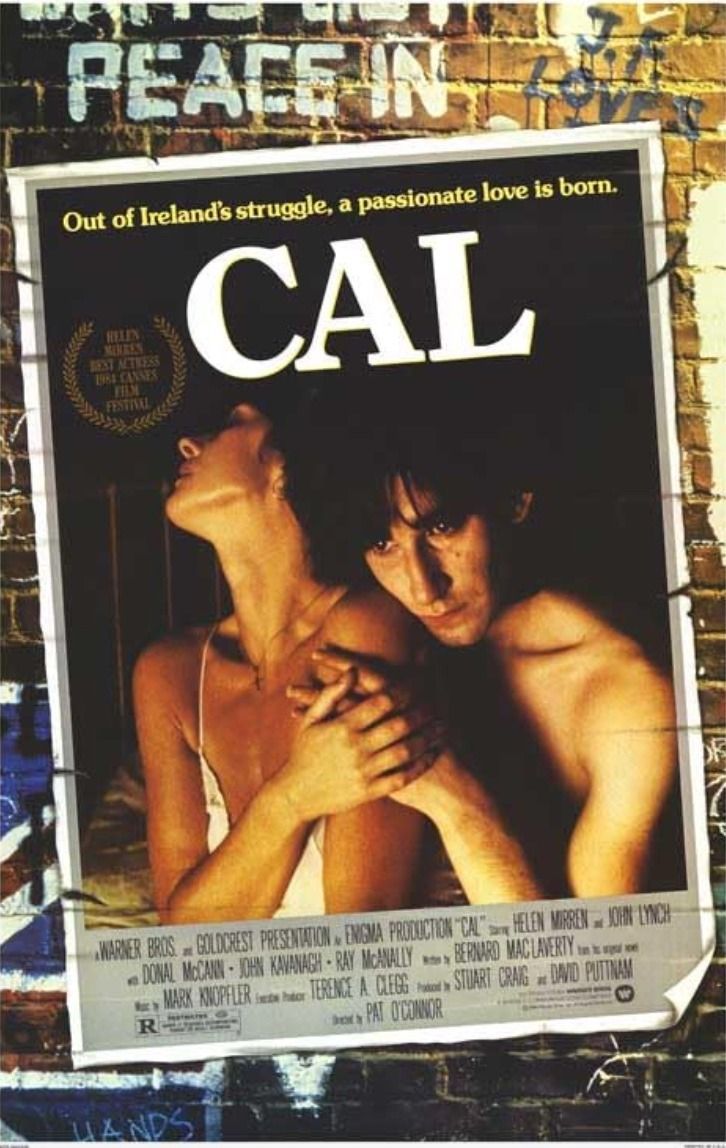

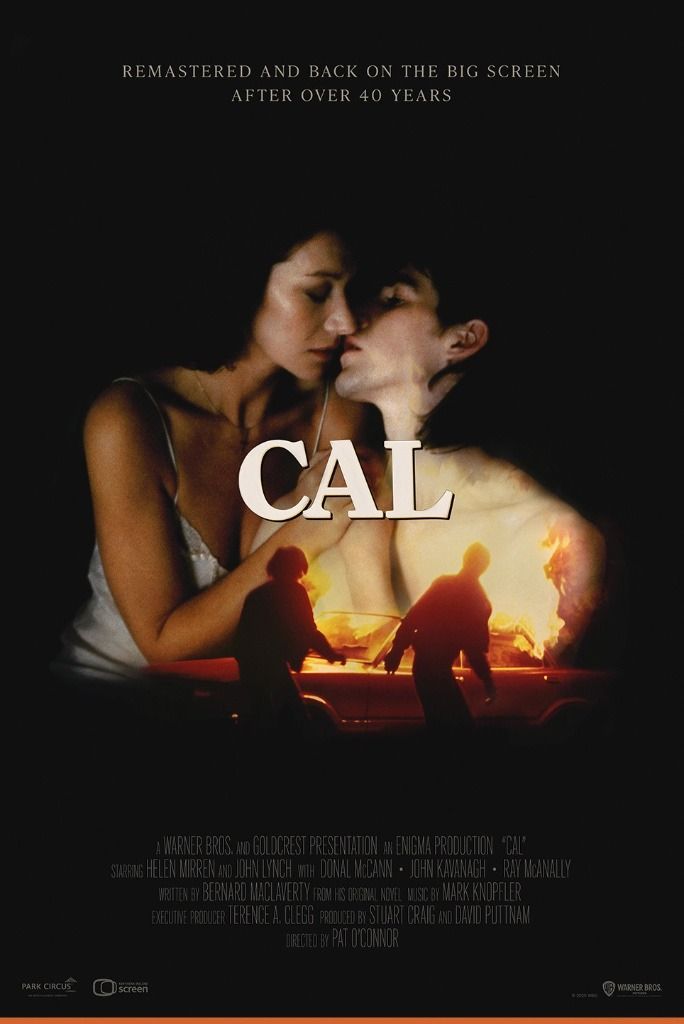

Magee's scene and its connotations came to mind as I sat recently in a darkened auditorium of one of those cultural oases, the Queen's Film Theatre, to watch a screening of the 1984 Troubles romance Cal (1984). Digitally restored from a damaged 35mm print and rereleased to mark the film's 40th anniversary, it stars Helen Mirren and local actor John Lynch (latterly of 'Blue Lights' fame).

The story is that of our titular anti-hero, a recalcitrant working-class teenager and tangential IRA member, increasingly alienated from his small-town Ulster existence and the banal sectarianism that permeates it. Drawn to the alluring Italo-Irish Marcella, widow of an RUC officer assassinated by Cal's IRA unit in the film's cold open, a budding romance begins, with predictably tragic results.

Based on a short story and screenplay from Belfast native Bernard MacLaverty, and featuring a moodily-scored soundtrack from Dire Straits frontman Mark Knopfler, Cal was one of those films - alongside the oeuvre of Neil Jordan - that marked the rise of Irish cinema in the 1980s and into the Celtic Tiger, boosting the QFT's profile into the bargain. The film's rerelease has accordingly taken place in a celebratory atmosphere, with much praise for the film's supposedly realistic portrayal of the conflict and its impact upon ordinary people, a triumphal procession crowned with maximum-stars review courtesy of esteemed Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw.

Mirren, in a preparatory pre-recorded video message aired before each screening, accordingly informs audiences of her excitement and pride in the film, for which she won Best Actress at Cannes in 1984.

If, like Magee's narrator, my Westie spider sense wasn't already tingling in response to this effusion of official praise (repressed memories of GCSE English and 'Across the Barricades' surfacing also) it certainly began to when Dame Mirren went on to inform us authoritatively, or perhaps a trifle defensively, that the reason the film was shot in Drogheda rather than on location in the six counties was because its makers were warned that to do so was "simply much too dangerous".

Curiously, whatever securocrat-cum-location scout that proffered this advice might have done well to inform venerable British director Mike Leigh likewise, given that in the same year he helmed the wonderful BBC Play for the Day 'Four Days in July', set and shot on location in Belfast, with scenes filmed at a variety of iconic sites located in the working-class coalface of the Troubles, including Ardoyne, the dilapidated Divis Flats and Beechmount (aka "RPG") Avenue.

Where Cal received lukewarm critical appreciation at the time, and now basks in the glow of critical posterity, Leigh's film merited a bemused reaction from the British establishment. Accordingly, it was never aired again by the BBC and its memorialisation is relegated to copies of an obscure DVD collection of Leigh's TV work. Bear in mind that not a single republican militant appears onscreen in 'Four Days', not is it a political thriller in the vein of Ken Loach's Hidden Agenda, likewise condemned by the British establishment: no one is shot or dies, and the only guns we see are those wielded by UDR soldiers in an otherwise prosaic scene. Leigh's error therefore one must assume was simply to have humanised the inhabitants of republican districts, that "terrorist community" that had the audacity to sympathise with the IRA and enthusiastically vote for Sinn Féin in the wake of epochal 1981 Hunger Strikes.

Suffice to say, Cal - while it shares with Leigh's film a naturalistic concern with the impact of the Troubles on everyday life - is not a film that needed to fear the censor's ban, given its caustic, cartoonish, depiction of republican militancy. The two IRA members given speaking roles, intended to embody the world of violent revenge that Cal wants to escape, could have been plucked from central casting: one, 'Crilly', a psychotic thug enthralled with violence for violence's sake (among his many other misdeeds, he cheerfully and gratuitously bombs a bookshop with a reluctant Cal in tow), and 'Skeffington', a Machiavellian upper-class commander who lectures our hero (in an incongruously honeyed Dublin 4 accent) on Pádraig Pearse in the smoking room of his mansion, while dismissively referring to his footsoldiers as "psychopaths" (in their presence).

While the former seems to have leaped onto the screen fully formed from the pages of an NIO press release circa the time of the film's release - a 'man of violence' and literal mad bomber, presumably 'on the backs of the community' - the latter is a concoction of the Conor Cruise O'Brien school of Troubles analysis, whereby the Provisional IRA's insurgency was motivated by Catholic nostalgia for the 'blood sacrifice' of 1916, and not discrimination, endemic poverty, British army massacres, loyalist atrocities, the collusion of the RUC, and a gulag archipelago stretching from the Castlereagh Hills to Magilligan Beach via the maggot-infested cells of the H-Blocks.

The only cliché missing was Skeffington's swivel chair, white cat and eyepatch. His every appearance on screen and over-pronounciated syllable drew appropriately vocal laughter from sections of the audience at the screening I attended. The ludicrous contradiction between this tabloid portrayal of the inner workings of the Provisional IRA, and every serious account of the post-Hunger Strikes period, which depict an increasingly professionalised guerrilla organisation, dug into a long war and led by a cadre of battle-hardened, working-class northerners, is painful to witness.

More tellingly, perhaps, to the film's liberal politics, the anarchistic mayhem of Cal's ASU are juxtaposed to the benign actions of British soldiers, portrayed as politely searching housewives shopping bags and opening fire at a roadblock only as a last resort, after appropriate warning is given, with only one resulting casualty: our pantomime IRA villain.

Readers of the Andytown News hardly need reminding of the gratuitous use of force (not to mention sectarian wisealeckry and sexual abuse) doled out by the real-life British army at roadblocks and checkpoints during its deployment in the North: in West Belfast alone the shooting of Harry Thornton, Frankie McKeown, Martin Peake, Karen Reilly as well as the disputed killings of republicans such as Stan Carberry and Pearse Jordan leap to mind, without recounting the famous murders of Aidan McAnespie or the Miami Showband (stopped at a false roadblock by active members of the UDR, probably under the command of Captain Robert Nairac, latterly of the Army's 14th Intelligence Company).

Aidan McAnespie was fatally shot on his way to a Gaelic football match in Northern Ireland in '88.

— Amnesty UK (@AmnestyUK) March 28, 2022

Today, 34 years later, the trial into his death begins.

The trial represents the due process that the UK Government is seeking to shut down for victims. pic.twitter.com/xoORKS3Zz9

Bear in mind a work of fiction depicting the Troubles need hardly conform to the ideological strictures of an An Phoblacht editorial circa 1987 to succeed as a work of art. Anne Burns' Booker-Prize winning novel 'Milkman' centrally features a thuggish, abusive Ardoyne IRA commander, while the entertaining canon of Irish filmmaker Michael McDonagh is populated with psychopathic republican paramilitaries and ex-paramilitaries.

Disney's recent controversial yet critically lauded miniseries 'Say Nothing', depicts a scheming, duplicitous Gerry Adams as its central nemesis. Indeed, surely even the most inveterate Provo would admit today that the IRA at all levels - like the Catholic Church, British aristocracy and armed forces - harboured abusers and bullies: men (nearly always men of course) who utilised whatever power they wielded over subordinates or civilians to malicious ends.

How could it be otherwise, given the staggering heights PIRA membership reached during the thirty-year conflict, driven by British blunders, callousness, and atrocities, and in the absence of an acceptable police force in those working class nationalist districts machine-gunned and set alight by the RUC in August 1969? The issue with Cal therefore isn't a negative, even damning, portrayal of the IRA, but that this lazy, formulaic, characterisation is merely symptomatic of its broader cack-handed approach to narrative verisimilitude.

While American author William Faulkner famously once stated: "All literature is simply the human heart in conflict with itself", those internal conflicts must be situated in a believable, breathing, universe, whether that's Middle Earth, the bridge of the Star Trek Enterprise, or the potato fields of mid-Ulster.

To achieve suspension of disbelief and audience buy-in, the world our characters inhabit must feel psychologically and sociologically real, and if you're portraying a real time and place in fiction, then you need to do so with the utmost accuracy and fidelity to the time, place, and community in which your story occurs.

There is attempt to add an air of eroticism and metaphorical heft to the conversations between Cal and Marcella, when the former ends up crashing at the latter's isolated farmhouse home, but they instead come across as prosaic and stilted.

It's on this criterion that Cal repeatedly falls down, epitomised in its simplistic rendition of republican paramilitarism and emphasised by its wider lack of attention to detail. Indeed, the film's portrayal of loyalist anti-Catholicism is as ham-fisted and quizzical as that inflicted upon their ideological nemeses. Perhaps the most unbelievable aspect of Cal's setting is that the titular character - a Provisional IRA volunteer bear in mind - and after 15 years of inter-ethnic conflict involving pogroms and the greatest population movement in peacetime Europe, still lives with his single parent father as the sole Catholic household of a 'kick the pope' Loyalist housing estate.

More bafflingly, when Cal is eventually taken in hand by the local gangs his persecutors restrain themselves to a gentle beating, rather than the statistically far more likely fate outcome of a slit throat, or worse. One of the more ludicrous examples of awry mise-en-scene occurs here, when one of the thugs attacking Cal is wearing a Union Jack cut-off top, like a tartan gang Geri Halliwell, a scene presumably intended to provoked dread and a sense of horror at sectarian perseuction, but which merely provoked laughter at my screening (that's twice if you're keeping count).

Educated viewers are likewise liable to be bewildered by the mishmash of accents we're presented with, with John Lynch - excellent actor though he no doubt is - caught between a London RADA accent (where he was a student at the time of his casting) and his native Newry brogue. Mirren, meanwhile, coached by her then-partner Liam Neeson, delivers us Ballyhackamore by way of Berkshire. The various supporting actors’ accents aren't any better, crisscrossing Ulster from one end to the other, with some opting for a guttural Belfastese and others a soft country burr. This linguistic confusion is topped off by the aforementioned Skeffington's Donnybrook enunication.

This aural confusion is compounded by the more glaring physical contradiction: the fact that Drogheda, with its iconic railway viaduct and terraced cottages - and for all its jerryrigged 'PIRA' graffiti and pasted-on technicolour Sinn Féin election posters - does not even slightly resemble Belfast or Derry, nor even Newry or Lurgan. Beyond banal architectural features, Cal doesn't even attempt to capture the suffocating military architecture of the period: the suffocating atmosphere of army and police surveillance that permeated republican districts of the period, drastically contraining local IRA units in when and how they could strike. In Cal the the British army and RUC are portrayed, ludicrously, not as an occupying force but as merely (and poorly) patrolling town centres while mischievous IRA volunteers, Cal among them, careen around in hijacked cars and carry out abductions, bombings, and armed robberies seemingly unhindered.

One might justifiably query whether it's fair to subject Cal to this sort of factual nit-picking given its entitlement to poetic license. That would indeed be a valid retort if the film wasn't marketed as a naturalistic portrayal of the conflict, nor if we lacked the aforementioned example of Leigh's 'Four Days in July', with its almost over-commitment to achieving theatrical realism in accents, locations, and power relationships.

Most damningly, even if one were able to traverse the uncanny valley of Cal, the film fails to function even as a self-contained romantic drama, dogged in particular by the absence of chemistry between the two leads. As the woke youth of today might point out, a "problematic age gap" mars the credibility of their romantic interactions, an issue that might have been overcome with better direction and acting, but Lynch is simply too young and inexperienced to carry such a heavy burden. His constantly-furrowed brow and the confused, bovine, expression he wears throughout the film - presumably intended to convey the character's feelings of deep inner turmoil - are reminiscent more of a man trying to remember whether he left the immersion on.

There is attempt to add an air of eroticism and metaphorical heft to the conversations between Cal and Marcella, when the former ends up crashing at the latter's isolated farmhouse home, but they instead come across as prosaic and stilted. At one point a heated argument erupts over the ethics of eating veal, presumably intended as a metaphor for the messy violence of the Troubles and Cal's own guilt, yet resembling more an Ulsterised episode of Emmerdale.

Prolonged scenes of lovemaking on the other hand are groan-inducing (and not the good kind), particularly when we are hammered unsubtly over the head with repeated flashbacks depicting Cal's role in the assassination of Marcella's husband while the duo approach climax. What might have had, on frayed 35mm film, an insouciant, art house, sensuality, is given, through digital restoration and Knopfler's overpoweringly "atmospheric" soundtrack, an inadvertent air of the 1980s made-for-television softcore drama.

The kindest thing that can be said about Cal is that it's an ambitious film, a worthwhile attempt to break through the sort of romantic stereotypes that taint the many Hollywood blockbusters set in the six counties and which portray the Troubles as as a simplistic conflict of good versus bad (on either side). The most honest thing, however, that can be said about Cal is that it's a bad film.