Tiarnán Ó Muilleoir on the Para mercenaries who went from Belfast to Africa to meet a brutal end... and how the story was covered by the Andersonstown News

JULY 10, 1976, as Britain and Ireland enjoyed record summer temperatures unmatched until last year’s record heatwave, half the world away three Englishmen were facing execution in an African jail. The three – Costas Georgiou, Derek John Barker and Andrew McKenzie – accompanied by lone American Daniel Gearhart, were brought into the exercise grounds of the Portuguese colonial-era fortress of São Paulo prison, located in the Angolan capital of Luanda.

There they faced a firing squad of military policemen appointed by the newly-established revolutionary regime of the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola). McKenzie, missing his left leg below the knee, faced the firing squad in a wheelchair in an ironic echo of the execution of Irish anti-colonial rebel James Connolly. Soon rifle shots rang out and two men fell dead instantly, with two survivors finished off. Punitive revolutionary justice had been dispensed.

Yet, remarkably, as the men’s bodies were being removed, it was found that Barker had in fact survived the initial fusillade and merely fainted. The firing squad’s error was quickly and brutally rectified, in the process bringing one of the most ignominious chapters in the history of neocolonialism to an end. For these four men were foreign mercenaries, hired guns recruited to fight on the losing anti-communist side of the civil war which broke out in Angola on Portuguese withdrawal in 1975.

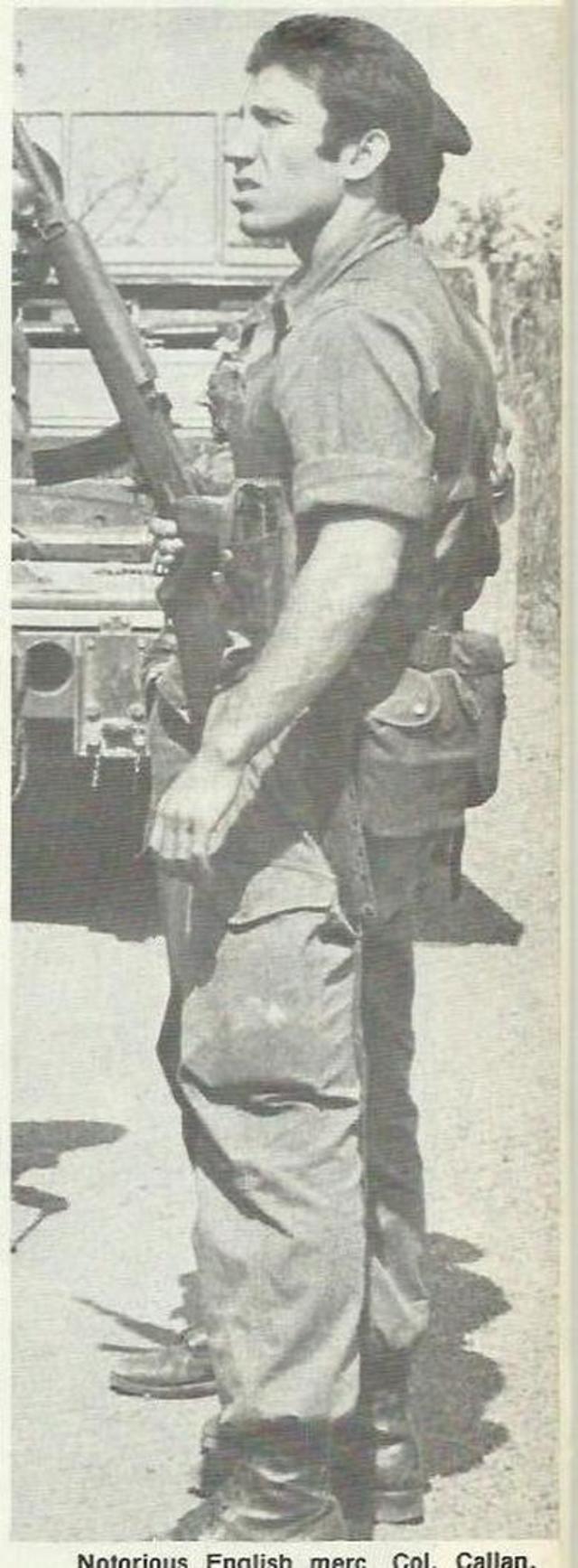

Costas Georgiou, aka 'Colonel Callan'

The Angolan Civil War, which was to last with interludes until 2002 – ultimately resulting in over 700,000 deaths – began in earnest with the Soviet-backed MPLA’s seizure of power in November 1975, sparking conflict with rival nationalist revolutionary forces that soon flared into violence.

Today in 1976 four mercenaries (one American and three British) are executed in Angola following the Luanda Trial. pic.twitter.com/u3Xkb6yAi6

— the painter flynn (@thepainterflynn) July 10, 2021

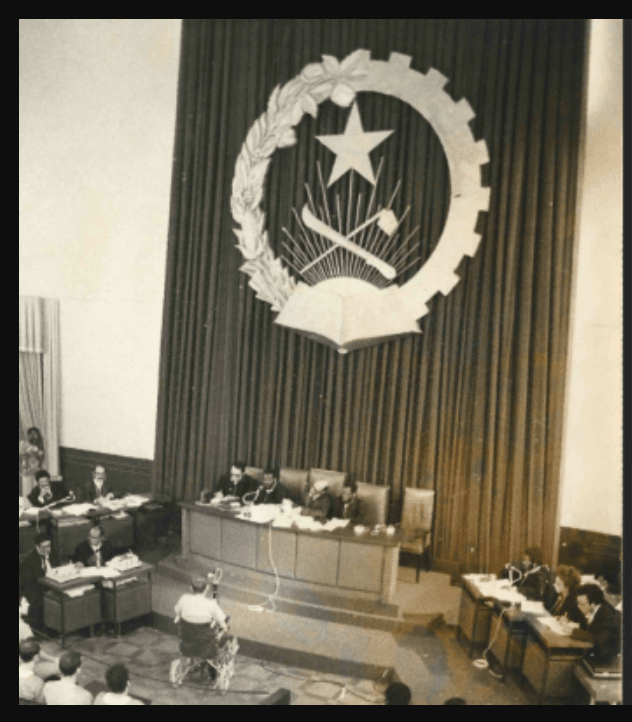

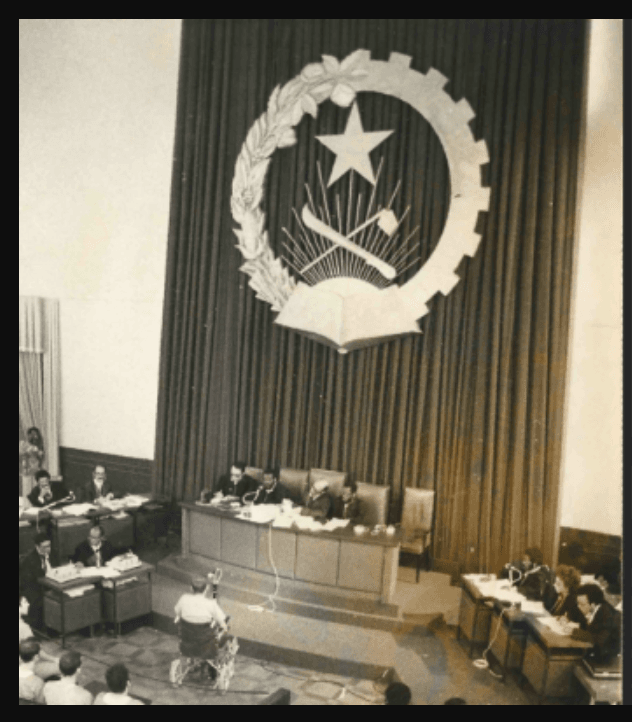

The result was the dual insurgencies of the US-backed FNLA (Front for the National Liberation of Angola) in the northwest of the country, and the Chinese-backed UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) in the country’s south. It was into this Cold War proxy conflict that western mercenaries, mainly Britons and Americans, were propelled. Poorly trained and equipped, after some initial successes they and their FNLA allies were overrun and captured by combined MPLA and Cuban forces and, in a gesture of defiance to the imperial powers of the West, a ‘People’s Revolutionary Court’ was convened to try 14 of the captured mercenaries for alleged war crimes.

At trial, it emerged that that the mercenaries had been recruited by a CIA front organisation, which in Britain operated under the telling acronym of SAS (Security Advisory Services), which shipped private soldiers to Angola on contracts beginning at a weekly pay of £150 (around £920 a week today). According to the MPLA-appointed prosecution, the mercenaries had participated in a range of atrocities including robbery, torture and mass murder, from their arrival in Angola in August 1975 and their capture in January 1976. From the mercenaries’ own testimony it emerged that their commanding officer Georgiou, alias ‘Colonel Callan’, had bought wholesale into the anti-communist crusade, undertaking a preparatory act of ‘domestic terrorism’ when he burned the MPLA’s London HQ to the ground in order to prove his bona fides to his new employers.

Western mercenaries on trial in Angola, 1976

His crimes in Angola itself, on the other hand, included the mass execution of 14 of his own men, supposedly for desertion. Prosecutors at the tribunal were able to establish that McKenzie, among other trusted lieutenants, carried out the sentence of death by machine-gunning and grenading the deserters as they attempted to flee. At the trial’s conclusion, Barker, Gearhart, Georgiou and McKenzie were convicted and sentenced to death, while ten other western mercenaries received lesser prison sentences. While Gearhart is known to have barely been in the country before his capture, and thus could be considered a relative innocent, the crimes of the mercenaries under Georgiou’s command were both horrific and corroborated by numerous eyewitness testimonies, both Angolan and foreign.

New release!

— Helion & Company Ltd (@Helionbooks) May 25, 2021

We are pleased to announce The CIA and British Mercenaries in Angola, 1975-1976 from our Africa@War series is now available.

✨ Save £3 off RRP until Sunday 6th June – no code needed ✨

Buy it here: https://t.co/Xif5g25gO7 pic.twitter.com/6nCidkZTs8

Yet, incredibly, none of these revelations tempered the stream of fervent appeals from the British establishment for clemency for the mercenaries. The tabloid press, the judiciary, Prime Minister Jim Callaghan and even Queen Elizabeth II condemned the Angolan ‘show trial’ and the sentences it handed down.

Or was this an outworking of that legacy of violence, a legacy which today’s Tory government is seeking to obscure by advancing the propaganda that the British overseas legacy is one of benevolent civilisation rather than colonial maltreatment.

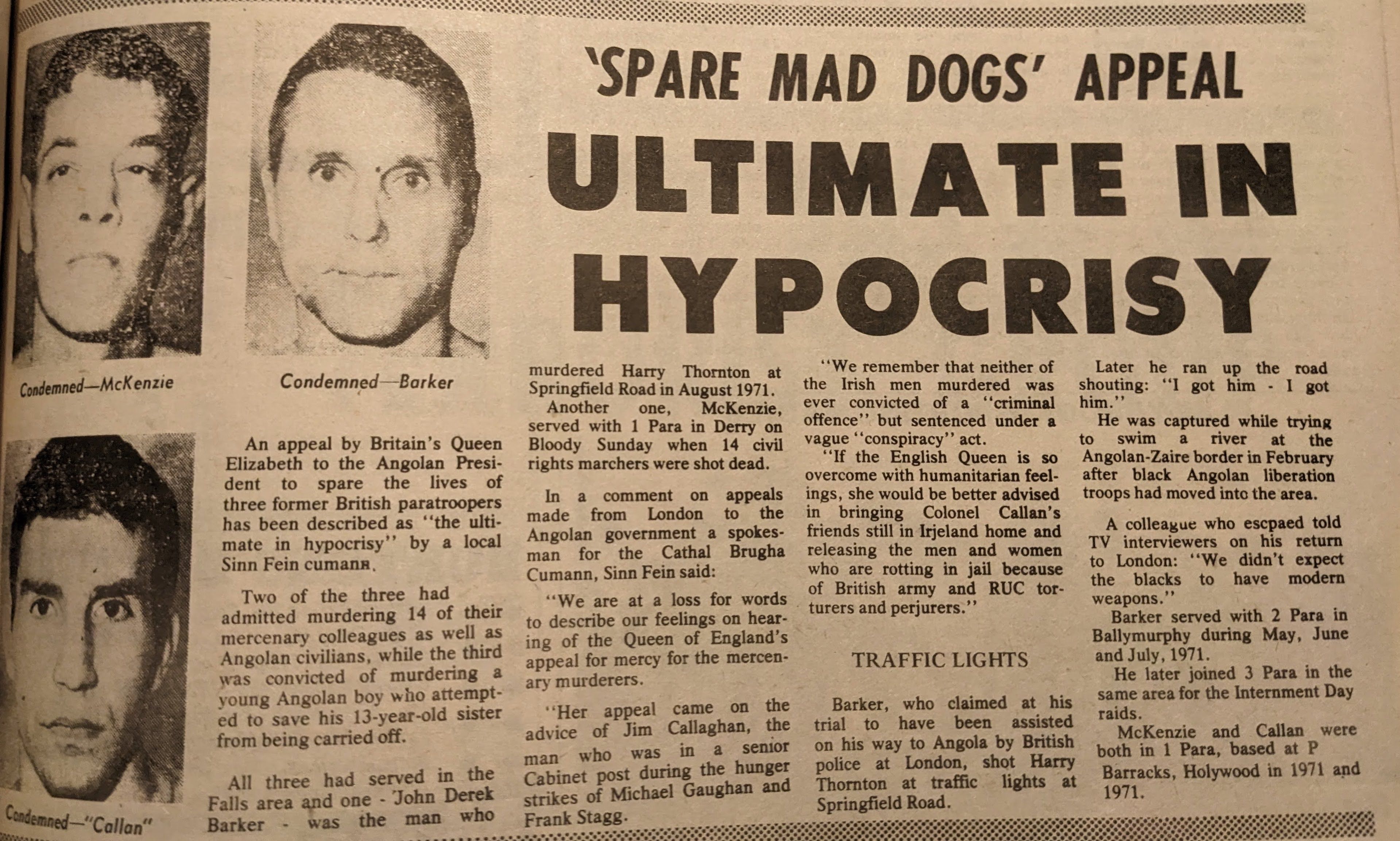

Amidst this outrage from the British ruling class, it fell to the Andersonstown News almost alone to highlight the sheer hypocrisy on display, as it demonstrated how several of those convicted by the Angolans had previous form for colonial war crimes. Eight of the fourteen mercenaries had served in the British Army in the six counties in the early 1970s, five of them with the notorious Parachute Regiment, including all three of those executed. The regiment’s crimes in this period included the infamous mass murders carried out in Ballymurphy during internment week 1971, Bloody Sunday in Derry in January 1972, and the killing of innocent workman Harry Thornton at a Springfield Road roadblock in August 1971.

Andersonstown News front page July 10th, 1976

Georgiou in particular, who spoke with Cypriot-accented English, was well-known as a thug and a bully on the streets of West Belfast during his deployment there. Eyewitness statements and contemporary reminiscences testify to his penchant for provoking nationalist youth into fistfights. Another ex-Para, and a cousin of Georgiou, Charlie Christodoulou, alleged to have murdered upwards of 50 Angolan civilians before being killed in an exchange with Cuban forces in the spring of 1976, likewise served in the North. Another ex-Para mercenary, Sammy Copeland, executed by his comrades in retaliation for his role in the mass execution of deserters, was also stationed in West Belfast during this period, with contemporary photos showing him with ‘3 Para’ in Vere Foster school in the Upper Whiterock in 1972.

Members of 3 Para pose for a photo in Vere Foster school army base - centre rear is Sammy Copeland, executed by his mercenary comrades in Angola for his part in the unsanctioned execution of alleged deserters

The Andersonstown News’ wisecracking columnist and vociferous critic of British Army misconduct, Nicky Tamm (the penname of Andersonstown News editor Frank Doherty), summarised events in the edition of June 19th 1976: “The British mass media are doing a great job on the Angolan War Crimes Tribunal. Every day we are told how the horrible Angolans are persecuting these young boys (average age 25-plus) because they were mercenaries. You may have noticed that of the 150-odd charges against them only one has been detailed by the British media – that of being mercenaries. So let me point out a few things."

29 February 1984: After UNITA captured 16 British nationals at Cafunfo, #Angola released the remaining seven British mercenaries it had held since 1976 #AngolanCivilWar pic.twitter.com/8UJZt0Mfnp

— Africa Bush Wars (@ModernConflict) March 4, 2021

“Firstly the main charge in that Luanda court are of mass murder. These cutthroats – eight of whom roamed the streets here in British Army uniforms before going off to shoot down blacks – killed men, women and children during a two-month reign of terror in Northern Angola. And the only fighting men they managed to kill were 14 of their own number. Having done that, and when confronted by Angolan liberation fighters who – unlike the women and children they killed – were armed, these brave boyos threw away their weapons and took to their heels in the best British Army tradition.”

Or, as another columnist, Homer of ‘In Vino Veritas’, put it: “You see negroes, like Irishmen, are not British – so killing them doesn't really count.”

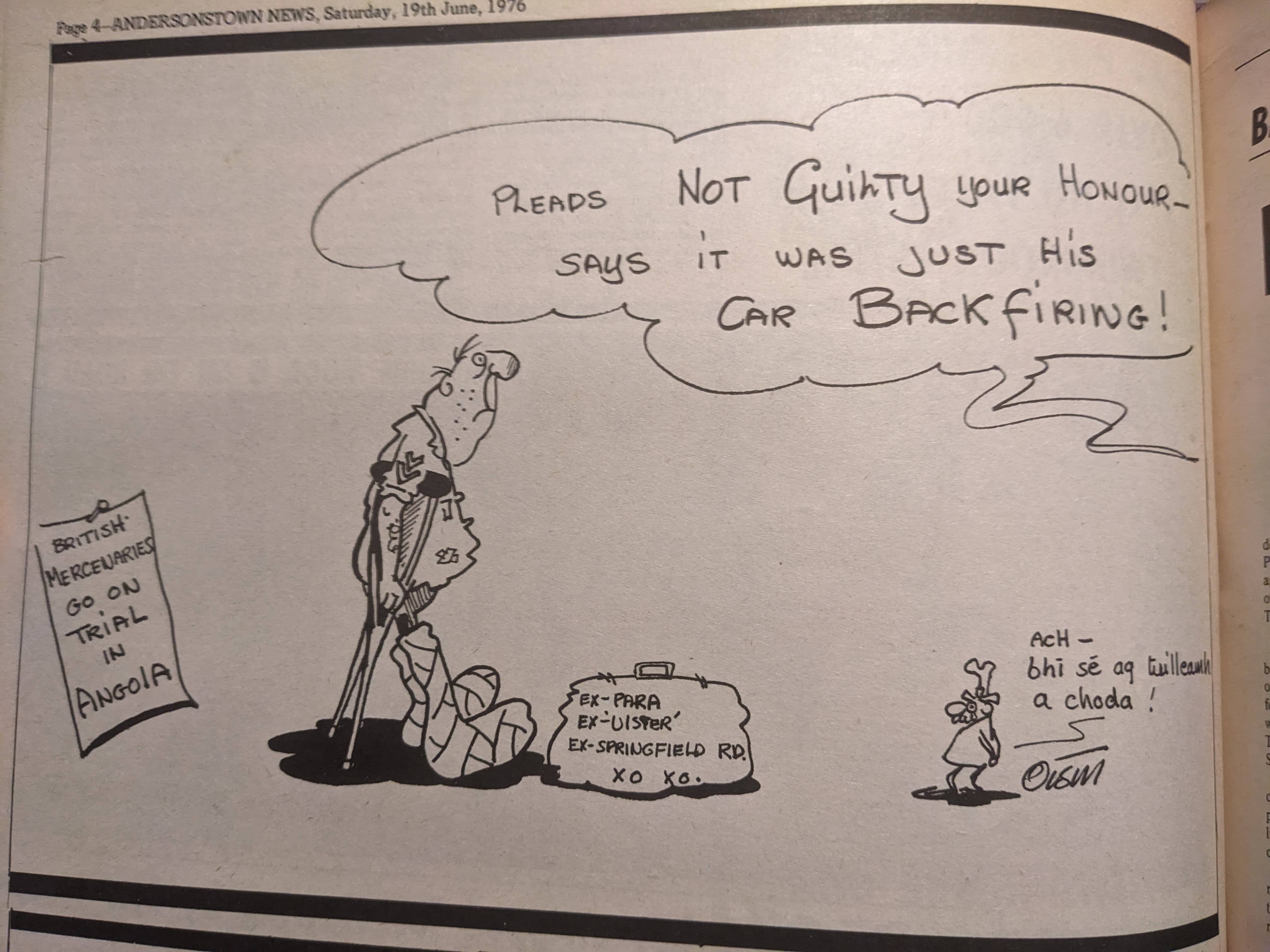

Oisín's cartoon of 19 July 1976

Historian Caroline Elkins recently has described the post-war dismantling of the British Empire in Malaya, Cyprus, Yemen, Kenya and Ireland as one which bequeathed a “legacy of violence’ to posterity. Brutal counter-insurgency to frustrate claims for self-determination and sovereignty escalated into concentration camps, internment, the suspension of civil rights and ultimately coercive force and the sponsoring of death squads in each case. The tactics innovated by Brigadier Frank Kitson in Malaya were applied wholesale to the six counties – ‘dirty war’ tactics that most recently re-surfaced in the alleged murder by British special forces in Afghanistan of hundreds of civilians unconnected to supposed Taliban targets.

Was it pure coincidence then that ‘crack’ troops, operating out of Holywood barracks under Kitson’s direct operational command, who were trained to dehumanise and subjugate the colonial subjects they confronted in Ireland, resurfaced as vicious killers of other colonised peoples half the world away in Angola? Or was this an outworking of that legacy of violence, a legacy which today’s Tory government is seeking to obscure by advancing the propaganda that the British overseas legacy is one of benevolent civilisation rather than colonial maltreatment.

The infamous Legacy Bill is only one of the most prominent examples of this politicised rewriting of history post-Brexit. As state murder becomes ‘privatised’, from Blackwater in the Middle East to Russia’s Wagner Group in Ukraine, the forgotten story of the Angolan mercenaries and their war crimes in Africa and Ireland is a reminder of how, when the crimes of the powerful remain unpunished, they yield a bloody harvest.