THE days of journalists being given a week, two weeks, a month, to go off and pursue single stories are virtually at an end. Long-form investigative pieces to all intents and purposes don’t exist any more and as newspapers struggle to come to terms with falling sales and dwindling readerships, the reality of life as a reporter has changed utterly.

When Ah were a lad, I thought journalists spent their lives in khaki shirts, chain-smoking and drinking like fish in between flights taking them in pursuit of whatever corporate, political or public target they were out to expose. And, hard as it is to imagine now, those exotic beasts did exist in the 70s, 80s and into the 90s.

The grubby, prosaic truth about contemporary journalism is a tale of surrender to the digital hordes. While the likes of BBC and RTÉ continue to take their morning news leads from the small cohort of what fewer and fewer people call the ‘quality press’ – the Times, the Irish Times, the Guardian, the Telegraph – the vast majority of newsrooms across these islands are little more than internet-scraping operations where chronically deskbound cyphers translate viral, mildly-viral and almost-viral social media incidents into tabloidese. And if journalists do jump on a plane, they’re more likely to be on their way to a corporate restructuring meeting at HQ than chasing an exclusive.

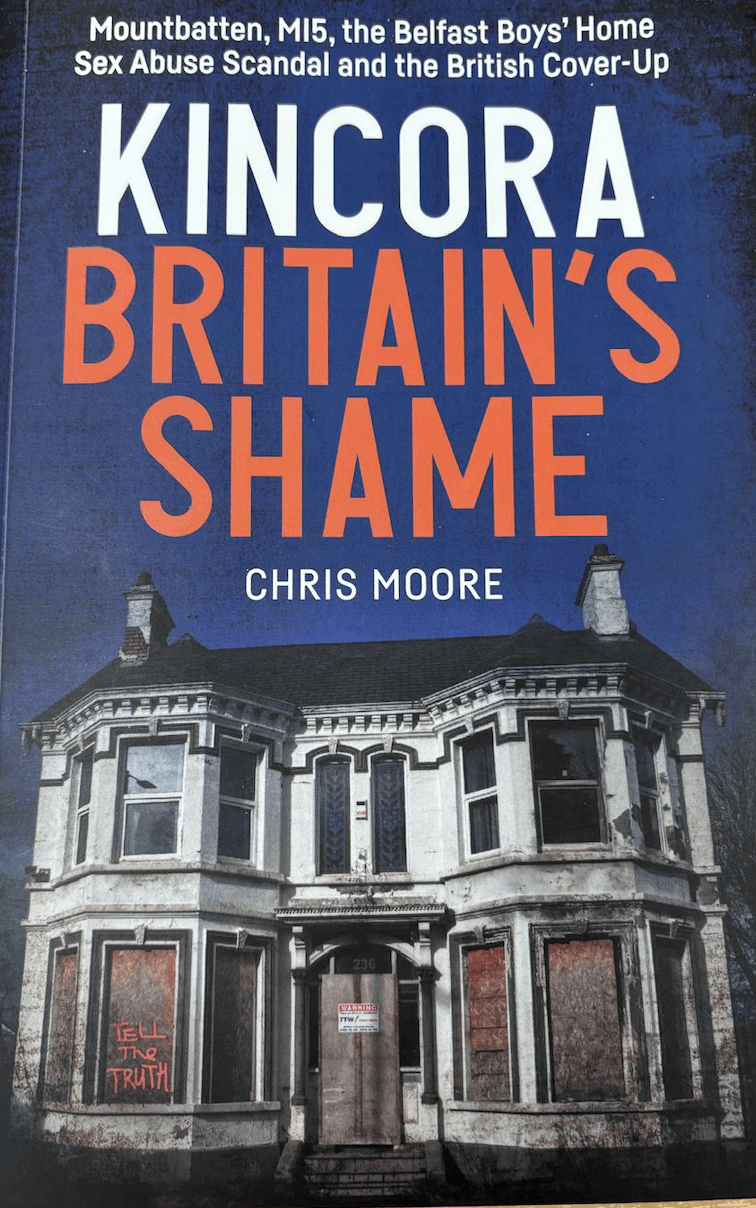

Chris Moore’s 40-year hunt for the truth about Kincora is journalism in the grandest tradition. For the vast majority of his working life and while employed by a range of media outlets – and himself – he’s been absolutely dogged in his belief that the recently-demolished East Belfast boys’ home is a ghastly and now ghostly repository of secrets and lies of an extent and magnitude that equals the historic scoops of those globe-trotting journalists of yesteryear.

Kincora has over the years morphed gradually from a grimly depressing but sadly familiar tale of sexual brutality in a criminally unregulated public facility to a jawdropping insight into the clandestine, intersecting worlds of British intelligence, loyalist militants, religious zealotry and royal depravity. The centrality of Lord Mountbatten – King Charles’ ‘beloved uncle’ – to Moore’s latest compendium of of corruption will of course grab the headlines, but as ever with Moore’s unflinchingly honest, humane and sensitive reporting, it is the tragedy of the unknown and uncelebrated victims which will stay with the reader the longest after the book is put down. And it is the role of the unknown and unseen MI5 puppeteers which will stir the reader’s anger.

For decades, Mountbatten’s reputation as a sociopathic pursuer of sexual adventure only added to his royal mystique. For what’s a royal family without sexually incontinent princes and priapic playboys? Straight sex, group sex, gay sex, bisexual sex in impossibly exotic locations and with jewel-studded sex toys gave Mountbatten and his equally promiscuous wife Edwina added cachet in the palaces and salons of Europe and beyond.

KEY FIGURE: Paedophile William McGrath was the house master at Kincora when it was a nexus of British intelligence and militant loyalism

But Moore has assiduously stripped away any last vestige of the shocking but legal glamour that attached to the Admiral with his GCVO, KCB and DSO. Mountbatten here is methodically disrobed of his starched naval uniform and his glinting medals and presented naked to us as the heartless, cruel, child-raping monster he was.

The book lays out the story in a clear and simple linear way reflective of Moore’s reporting over the years – and it’s a compelling read because of it. Beginning with the disgustingly banal details of the lives and crimes of the professional, political and religious lives of the three men who ran Kincora, it quickly gathers pace as Moore peels away the onion layersm, and that unpeeling may well have you crying tears of pity – and anger.

For instance, the connection outlined in the book between the notorious paedophile and Kincora housemaster William McGrath and the formation of the modern UVF gives a chilling sense of how the roiling politics of militant unionism in the mid-60s catapulted us towards the conflict that erupted in August 1969. When Gusty Spence was arrested and charged with the June 1966 murder of Catholic barman Peter Ward and the attempted murder of two his friends – the first act of violence of the renascent paramilitary group – McGrath went all out to get Spence out. He visited Ian Paisley in an attempt to enlist his support, sharing with him a bizarre story he had concocted that the three young Catholic victims were communists who had infiltrated Spence’s local, the Malvern Arms.

We are left to speculate on how Paisley reacted to the attempt to suck him into the world of paramilitary violence, but the wealth of anecdotal evidence linking the North Antrim Protestant firebrand to the UVF gang responsible for the later spate of false-flag attacks on utilities north and south speaks for itself.

Moore reveals that Spence later told him in an interview that he had merely been a pawn used by others – the Malvern shootings were not a reaction to the threat of IRA violence, he had been manipulated by a shadowy, hard-right cabal aimed at ending the Premiership of Terence O’Neill. The outworkings of intra-unionist tensions centring on an unprepossessing religious zealot in East Belfast would condemn us to three decades of bloody and bitter conflict.

The chapter ‘Face to Face with McGrath’ is an absolutely compelling account of the author’s meeting with the face of Kincora in the loyalist County Down village of Ballyhalbert in February 1990. As is so often the case in the best journalism, persistence and educated guessing were helped along tremendously by a generous dollop of good luck. After a negative response in a local newsagents to Moore’s attempts to locate McGrath’s address, the then BBC reporter was sitting in his car considering heading back to Belfast when “an elderly man approached, wearing a cardigan, dark trousers and slippers, so obviously he had not travelled too far.”

I shared the jolt of adrenaline Moore must have experienced when encountering McGrath in the wild – and what follows does not disappoint. Eschewing gaudy tabloid-speak for a straight, unsensational reporting style, Moore reveals to us a man skilled in the art of communication and deception, a stubborn man, a manipulative man – clearly someone keen to justify himself to the world, but lacking the courage to expose himself post-prison to the publicity that that justification would require.

In many ways, that encounter with a pensioner outside a seaside sweet shop is more revealing – certainly more memorable – than the Lord Mountbatten information outlined a little later. Is that because in the wake of the Prince Andrew revelations we’re no longer as inured to royal family crimes, or is it that endless tabloid and social media coverage of King Charles and his rift with Meghan and Harry has stripped the glamour and fascination from the House of Windsor? Whatever the reason, Mountbatten, despite the endless letters after his name, his many titles and his Gilbert and Sullivan uniforms, sits comfortably in the seedy, vicious, callous world of Kincora, McGrath and his workmates.

PREDATOR: Lord Mountbatten abused boys at Kincora and at his holiday residence in County Sligo

The testimony of Mountbatten’s victims is made searingly credible and painfully vivid by the little details that give heft to their accounts: An ensuite shower room is a thing of wonder to Arthur, a boy who’s never seen one; that small boy is made to stand on a box to give him height before he’s raped and abused; that boy watches TV while being watched by a predator; a rapist tells that boy to be careful he doesn’t hurt himself while sliding down the banister. The authenticity is chilling – and it’s heartbreaking.

There he is in a downstairs room in Kincora in the late 70s – Mountbatten in civvies, patiently waiting for a boy to be brought to him. He’s introduced to Arthur as ‘Dickie’ and the perfunctory, clinical nature of the rape as described by the victim is almost too painful to bear. A boy with a bleeding anus, in a house in Belfast, ten minutes from my house, used and abused by a royal rapist who has just left to get a Royal Air Force flight back to whatever palace he’s staying in that evening. The image was enough to make my heart and my stomach change places.

Chris Moore’s book is a vital read, but it’s a very difficult one. In other hands it might have been an impossible one, but the author delivers his story with an understated empathy that manages to give the victims the dignity that others tried to strip from them. And he performs the not inconsiderable feat of doing so without detracting one iota from the book’s sheer readability.

It’s an extraordinary feat of reportage – and humanity – that only someone who has devoted his life to a story, and its victims, could achieve.

•Kincora. Britain’s Shame. By Chris Moore. Merrion Press. Available in all bookshops and online.