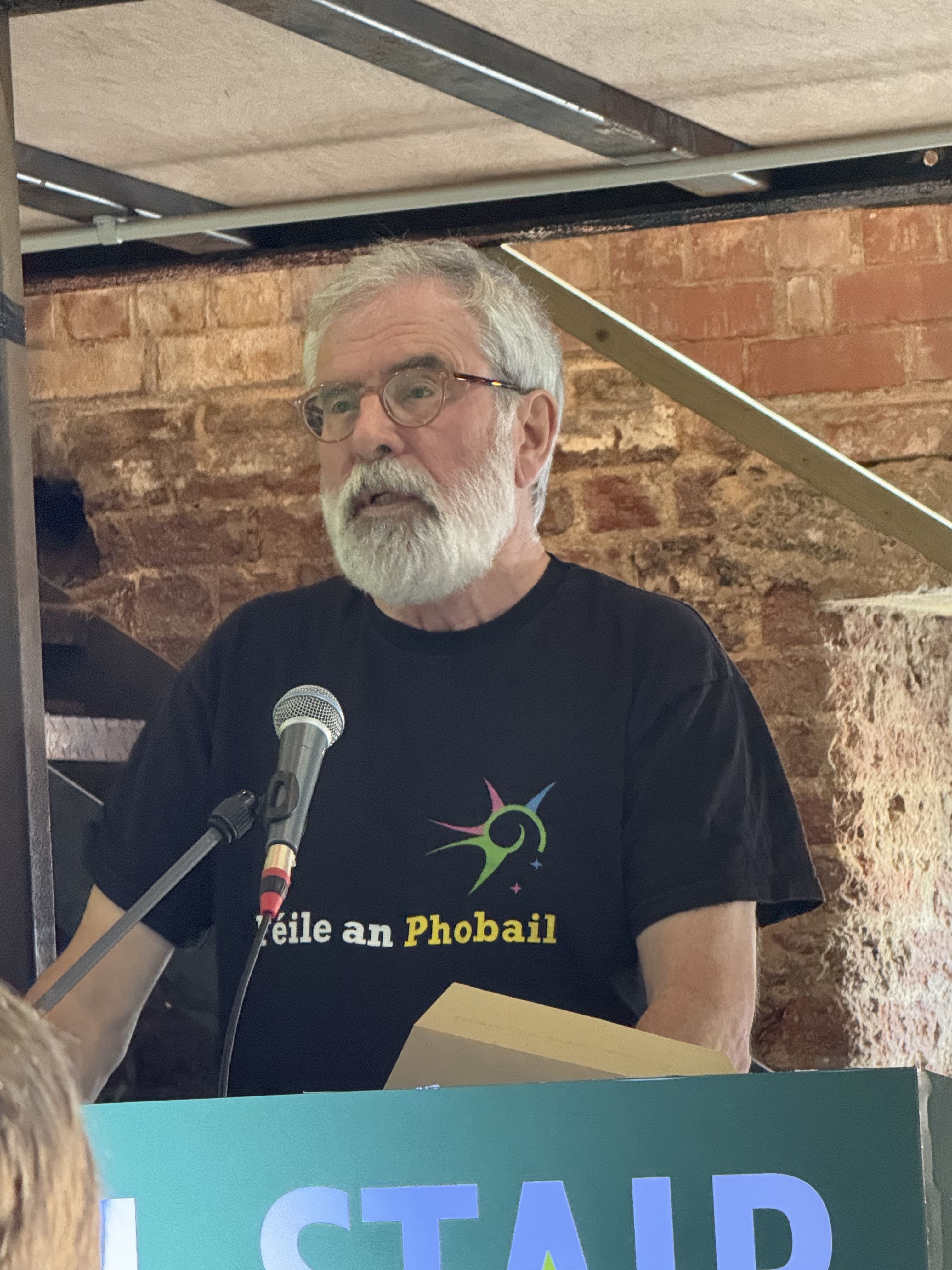

WELL done to all of those who planned, organised, participated in, or generally contributed to this year's hugely successful Féile an Phobail. It was a colourful, imaginative, informative, entertaining, empowering and exhausting couple of weeks.

This year’s published programme was a weighty volume, providing information on over 600 events across the City. It was a mix of 80 debates and discussions, sporting and music events, art exhibitions, as well as the carnival parade and family fun days for children and much more. The concerts in the Park were packed to capacity each night and revellers thoroughly enjoyed themselves.

It was also Tom Hartley’s last year providing a guided tour through the City Cemetery’s history of Belfast. Tom is a renowned historian whose books on the City, Milltown and Balmoral cemeteries have added enormously to our understanding of Belfast, its complex politics and social fabric.

He was 80 this Wednesday and after years of walking the City Cemetery he decided the time had come to hang up his walking boots. It was an emotional final walk last Saturday at the end of which I thanked Tom for his years of activism – which will continue – but in particular on that day for his journey through our graveyards and the story of Belfast.

The plight of the Palestinian people was never far from Féile with Palestinian Day attracting big crowds and Avi Shlaim, an Israeli historian here talking to a packed hall in St. Mary’s about the genocide in Gaza.

The theme of Irish Unity permeated many of the talks and panel discussions, including in Uachtarán Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald’s conversation with Andreé Murphy. A new journal An Clógan was launched to provide a platform for Socalist Republican writers and thinkers.

As always sport was a big feature of the Féile with 5k and 10K runs, the annual Poc Fada on the mountain and GAA games galore. Corrigan Park was the venue for a 'compromise rules' match ‘Between the Sticks’ showcasing the sports of hurling, shinty and camogie. Two teams from Scotland participated - a men's shinty team from Stirling and a women's team from the Isle of Skye. They were brought to the event by Presbyterian Church in Ireland minister, Rev David Moore. It was a great day out for all.

Last Thursday 31 July, St. Mary’s was the venue for a fascinating talk by Researcher David S Dunlop on Presbyterianism and the Irish language. Evidence of changing times was to be found in the presence of members of the Free Presbyterian Church in the audience.

So, a big thank you to Kevin and the Féile team. A hearty comhghairdeas to all who helped make Féile 25 a huge success. Féile 26 here we come!

GaelStair – Ná habair é, dean é

During Féile, I had the honour and pleasure to open an exhibition in Conway Mill on the role of the Irish language and Irish language activists in the social and political history of Belfast. At the heart of the exhibition is the archive preserved by Brighid Mhic Sheáin - one of the founders of the Shaws Road Gaeltacht in West Belfast.

Over five decades she diligently collected the GaelStair archive which reveals how connected the Irish language was with the struggle for social rights, self-determination, and for a better future free from poverty and unemployment.

The exhibition is a remarkable account of the work of those early pioneers from the 1930s and later who not only sought to save the language but also create a society where people would be uplifted, economically, culturally, and spiritually.

Seán Mac Goill features prominently in this exhibition alongside his friends, peers, and comrades - who gave us the urban Gaeltacht at Bóthar Seoighe and Bunscoil Phobal Feirste. They were also part of a radical cohort who rebuilt Bombay Street after it was burned down during the August pogroms of 1969.

More recently, I remember at the height of our campaigning for Acht na Gaeilge and other language rights Seán or Séamus Mac Seáin – I always get the two mixed up – stating that while we had to campaign for legal entitlements we cannot wait for them. That meant taking initiatives. This encapsulates the activism of this particular generation of visionaries and activists. The credo of 'Ná habair é, déan é'.

When I first saw this exhibition I was reminded of the words of Máirtín Ó Cadhain who said that language activity, “has two aspects, one of resistance and the other of positive demands.” He also understood the link between the language and social and economic issues. He said: “Issues should be chosen with care. It is better they should not be exclusively concerned with the language but connected with other matters of public interest.” The exhibition gives us a real sense of the merits of these words and of the challenges faced by Gaeilgeoirí.

When prisoners were released from the Blocks, many brought the language skills and teaching methods they had learned back into their communities. The challenge for us is to continue that work. To ensure that the Irish language is a central part of the new, equal Ireland that we are building."

That undauntable ethos was found in the Gaeilgeoirí who sought to create a self-reliant community, through initiatives like Siopa an Phobail, Iontaobhas na Gaelscolaíochta, and others. And today that ethos and legacy are evident throughout west Belfast: Cumann Chuain Ard, An Chultúrlann, Glór na Móna, GaelChúrsaí, Conway Mill, Raidió Fáilte, An Cheathrú Ghaeltachta , Coláiste Feirste, seven gaelscoileanna in Iarthar Bhéal Feirste, Áras na bFhál, and Spórtlann na hÉireann.

The Irish language is now stronger in Belfast than it has been in centuries, and stronger here than any other urban centre in Ireland. This happened because of the hard work, sacrifice and vision of the generations that went before us.

It happened also because of the example and work of the political prisoners whose use of the language, especially in the H-Blocks, had a huge impact on the consciousness, particularly of young working-class nationalists. Bobby Sands’ leadership on the language issue and his death also had a huge effect.

When prisoners were released from the Blocks, many brought the language skills and teaching methods they had learned back into their communities. The challenge for us is to continue that work. To ensure that the Irish language is a central part of the new, equal Ireland that we are building.

An Cheathrú Ghaeltachta is a part of this. The potential for An Cheathrú Ghaeltachta is as high today as it was when founded in 2008. There is enormous enthusiasm, particular among the new generation of Gaeilgeoirí. The success of An Dream Dearg is evidence of this.

However, we cannot be complacent. The reality is that the Irish language and culture still face the legacy of colonialism. As evidenced in the lack of investment in Gaelic games, or the negativity over street names in Irish or bi-lingual signage in a bus station or the delay in building the new Casement stadium.

The key to growth in the language is to ensure that it is relevant to our everyday lives. This exhibition is an example of the determined activism of Gaeilgeoirí. The men and women represented in this exhibition and their peers are laochraí. Outstanding Irish patriots. Their work is a source of inspiration for us all.

Remembering Internment

As we celebrate Féile an Phobail, we should remember the events of August 1971 which gave rise to some of the conditions that helped shape Féile in 1988.

In the early hours of Monday 9t August 1971, thousands of British soldiers swamped nationalist areas across the North and smashed their way into the homes of hundreds of nationalist and republican families. 342 men, the old and the young, were dragged from their beds and taken to interrogation and holding centres where most were beaten. Fourteen of their number were singled out for torture – the Hooded Men.

The Unionist Stormont regime had demanded internment and the British Government agreed. The result was a dramatic escalation in conflict. 14 people were killed that first day. Five of them were shot dead in Ballymurphy. The first of ten killed in the Ballymurphy Massacre. Thousands fled their homes with an estimated 5,000 becoming refugees in camps in the 26 counties run by the Irish Army.

Internment lasted until December 1975. It reflected the dominant ethos of the British and Unionist systems. Both believed internment and increased militarisation would end the popular uprising that arose from the August 1969 pogroms. Between 1971 and 1975 an estimated two thousand men and women, over 95 per cent from nationalist areas, were interned.

Following a court case, I took several years ago it emerged that between 300-400 internees were illegally detained during those years. The British Government had not followed their own special laws. It has decided that none of these men are entitled to compensation. The law is being changed to make legal what was illegal five decades ago. A perfect example of corruption at the heart of the British system when dealing with Ireland.