‘WINDRUSH: Portraits of a Generation’ (BBC Two ) was a bit like Sky’s ‘A Portrait of the Artist’, except that it had a social and political dimension.

The Windrush generation was, of course, those people from the West Indies who came to Britain in the post-World War II years, keen to help reconstruct Britain and expecting to receive a warm reception for their fighting and dying alongside British soldiers in the war. The weather in Britain proved a lot damper and colder than they’d anticipated and the frostiness of their reception was best caught in the windows of lodgings: ‘No blacks, no dogs, no Irish’.

The portraits to be painted were organised by King Charles, who said it would “celebrate the immeasurable difference they, their children and their grandchildren have made to this country."

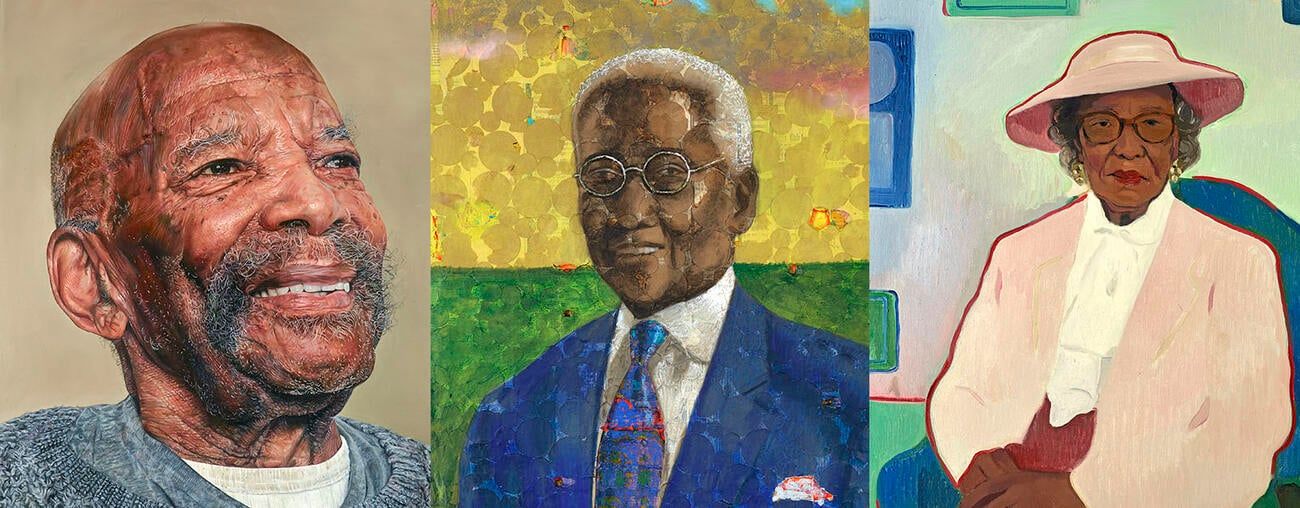

The people painted were black and the painters were black, and as the paintings were planned and actioned, the subjects told something of their story. One woman worked as a nurse auxiliary in a hospital for over twenty years. “Some of the patients were prejudiced – I just laugh and walk away.” Back in the West Indies, they had been taught all things English. One man spoke of being taught to sing ‘My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose’ only to have his parents demand, “Why they teaching you to sing these dirty songs and you are just a boy?”

There were ten elderly Jamaicans chosen to have their portrait painted, with Professor Sir Godfrey Palmer the major success story in the group, but even he told of pub landlords who would stack up bottles so patrons could throw them at the black guy who'd just come in. And when he came back to London and told his family he now had a degree, some of them thought he was talking about having a temperature. Another success story was a woman of colour who was appointed to the Police Commission, which sometimes put her in a difficult position since the police and the Jamaican population didn’t always get on well.

When the landladies, the police and the Teddy Boys have it in for you, you know you’ve got problems. Many of them learned how best to deal with it: “You gotta rise about discrimination, not allow it to nibble away at you, become a burden, leave you disenchanted see the positive side.”

“You kind of swallowed the lump and carried on.”

King Charles and his missus Camilla clearly thrilled these old West Indians – imagine, me in Buckingham Palace, talking to the King and Queen and having my portrait on display!

“Our society is woven from diverse threads," Charles told them, and they loved it. You could say that by mounting the paintings, Charles pleased and excited these people who for decades struggled to fit into British life. You could also say that Charles at the same time burnished his image as an empathetic, fair-minded man. You’d hardly believe there were members of the royal family who worried that Prince Harry’s son might look too black.