“THE town now resembles a camp, so numerous are the military forces drafted into it…were it not for their exertions the streets would now be deluged with blood.” (London Evening Standard – 1872)

A week of vicious rioting and sectarian conflict in Belfast was referred to in contemporary press accounts in August 1872 as the “Seven Day Civil War". The London Times described the riots as a “sudden and brutal convulsion”. At their end on 24th August, military and police numbered 4,400 men under arms to hold the line in Belfast.

Sectarian riots in Belfast can be traced back as far as 1835, later 1843, 1857, 1864, and later; all invariably linked to the Orange Order, fiercely antagonistic to Catholicism and Irish nationalism in Belfast, provincial Ulster and throughout Ireland, especially in the second half of the 19th century. Orangeism was also supported by the notorious 19th century Protestant firebrand preachers, most notably Dr Henry Cooke and his infamous disciple, the Belfast based Reverend ‘Roaring’ Hugh Hanna of St Enoch’s Presbyterian Church opened in 1872 at Carlisle Circus, north Belfast. Notoriously anti-Catholic they were fanatical believers and preachers of the Pope as the ‘anti-Christ’.

In 1845 The Northern Whig said: “Whilst there are always a body of clergymen whose zeal is turned, without ostentation, to the duties of their profession, there is also a standing force of clerical brawlers, who delight to embark in agitations and to work upon the worst passions of the human heart on all, however, under the pretence of piety, and 'for the good of immortal souls'. This class of clergymen are among the greatest pests of society.”

The Party Processions Ireland Act 1850 to 1872

The Party Processions Ireland Act was passed by the British government in 1850 prohibiting open marching, provocative sectarian demonstrations/political processions in Ireland. The Act repealed in 1872 is critical in understanding the 1872 Belfast riots. Monster meetings were held across Belfast and Ulster on the 12th July and 12th of August by the Orange Order and afterwards nationalists planned similar monster meetings to assert their aspirations as nationalists in support of the Home-Rule movement.

One meeting was attended by 80,000 of the Protestant tenantry in Fermanagh.

Resolutions passed indicated their ‘fears’ of the growing power and self-confidence of Irish nationalism, “… believing that the demand for Home Rule, if granted, would result in the disintegration of the Empire, and the establishment of a Papal ascendancy in Ireland, we pledge ourselves to resist to the utmost a policy so adverse to the interests of Protestantism, and to the welfare and prosperity of our country".

Hannahstown Meeting of Nationalists: Thursday 15th August, 1872

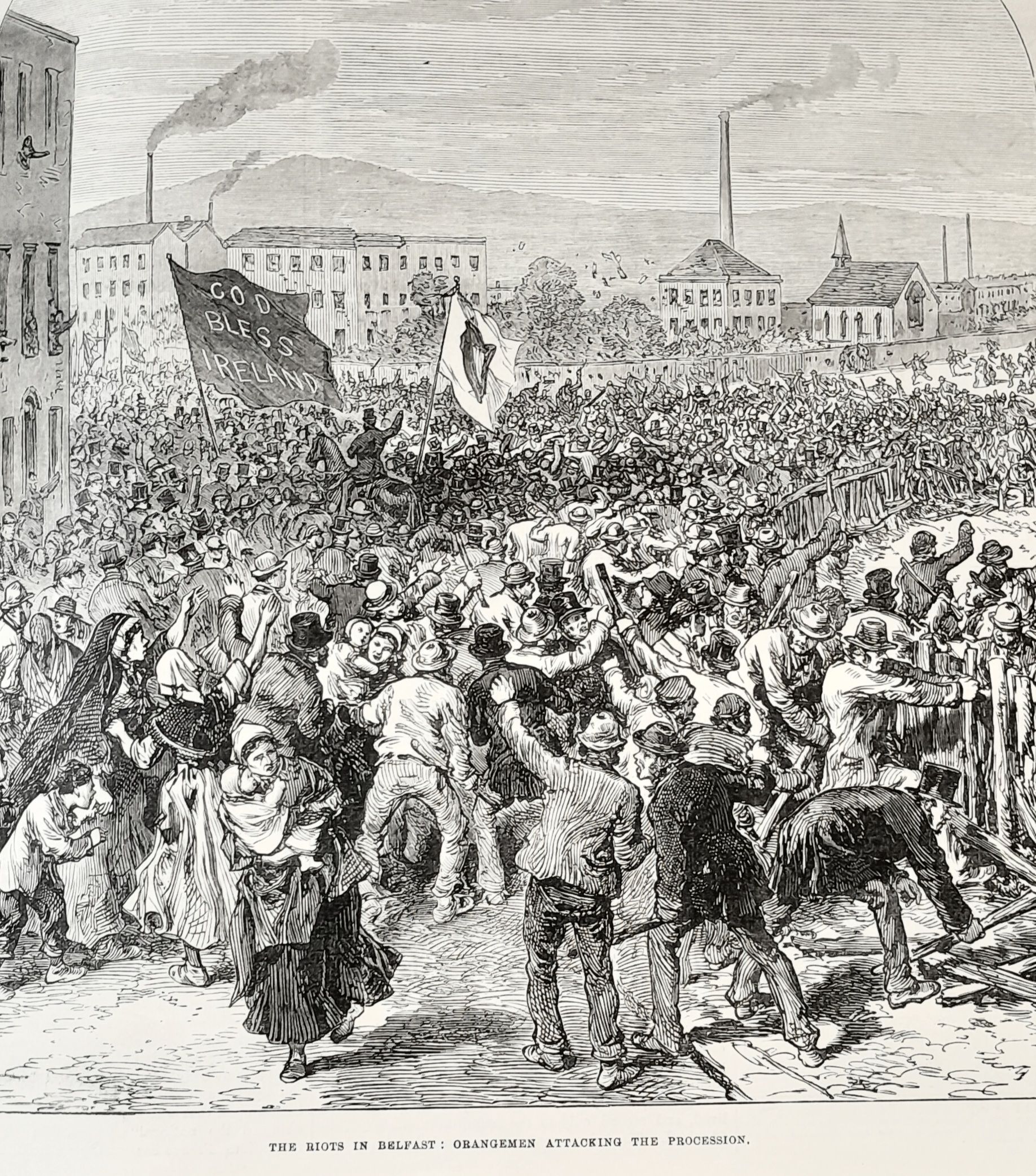

The largely Catholic and nationalist procession was allied to the emerging Irish nationalist campaign for Home Rule, and was held on Thursday 15 August 1872 (the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, known as ‘Lady Day’). Subsequently major sectarian riots erupted in Belfast lasting until Thursday 22 August, instigated by the Rev Hugh Hanna.

It was planned to commence the Lady Day procession at ‘Carlisle Circus’, proceed to Hannahstown, return and disassemble at the Carlisle Circus starting point. The assembly point was objected to by Shankill Protestants, the Orange Order, and most especially by Rev Hugh Hanna who disingenuously claimed to the Orangemen in the Shankill that his church, St Enoch’s, could come ‘under attack’ by the nationalist/Catholic Home-rulers. The Carlisle Circus plans were prevented by a large police presence and the parade rerouted as many as 5,000-10,000 loyalists had assembled behind police lines to ‘defend’ St Enoch’s at Hanna’s bidding’. This was nonsense; neither he nor the Shankill Orangemen wanted the ‘disciples of the devil’ – ‘papists’ – contaminating Protestant ‘owned’ Carlisle Circus.

The nationalist procession was ambushed twice, and viciously attacked, first at Peter’s Hill at Shankill Road shortly after at the waste ground known as the ‘Brick Fields’, dividing Shankill and Falls. Fierce fighting erupted as nationalists defended themselves, before succeeding to continue to Hannahstown.

The Hannahstown meeting was described as a “monster demonstration” with 30,000 in attendance. (Another estimate was 100,000). It was addressed by Joseph Gillis Biggar, member of the Town Council and President of the Belfast Home Rule Association. Two motions were approved unanimously – to demand from Gladstone’s government the release all political prisoners of the Fenian Movement and secondly to advocate in every way for the aims of the Irish Home Rule Movement.

The Newsletter published a letter from ‘Loyalist’ on March 16:

“Sir—Belfast has at last seen the outpouring of its slums in a very numerous swarm of the disloyal and dangerous classes… It was an invasion by Romish rowdyism of respectable Protestant localities…and then the Lady Day men attempted to air themselves at the Carlisle Circus. That is one of the most Protestant districts in Belfast or in all of Ireland. St Enoch’s Church (the Rev H Hanna’s) is there, and the Lady men attempted to display in front of it their disloyal symbols.”

Contemporary Map of Belfast showing main areas of rioting, gunbattles and evictions

Belfast in a State of Civil War

On Thursday evening there were sporadic disturbances and violent outbreaks between nationalists, loyalists and police in different parts of the town, with some injuries sustained. At 2pm, 500 shipyard workers marched into town after hearing Hanna’s orchestrated rumours that St Enoch’s Church at Carlisle Circus would be attacked by nationalists. They were armed with hammers, clubs, iron bars, rivets, bolts etc and attacked a police cordon at York Street and Donegal Street. They were eventually repelled and countless arrests made.

From Friday 16th, Belfast erupted into an orgy of sectarian violence. ‘Eviction gangs’ formed on both sides and began giving two-hour notices for Protestant and Catholic families to get out of their homes and districts or be put out. In other cases, mobs simply ransacked houses, took families’ belongings and burned them in the streets. Families sought refuge in safe areas with other family and friends or fled elsewhere; large numbers of refugees escaping town was a feature of the ensuing week of rioting.

Notices of personal intimidation were widespread. On one prisoner was found a note addressed to a member of the fire-brigade:

“I beg to tell you that you are to leave this before tomorrow night, if you value your life. It is a friend who wishes you well that gives you this notice. Now, if you value your life take this warning. You are to be shot. That is your doom.” At the end of the sketch was a rude sketch of a coffin.”

The Newsletter reported scenes of an evicted family in Donegall Street at 7am on Monday 19th August. “A, very indifferently clad, but apparently very decent for his rank in life, was going along with a handcart laden with some miserable furniture, a bed-tick, a table, one or two chairs and a bag of coals. A friend trudged behind, carrying a clock in one hand and a pendulum in the other, while his wife, a poor frightened-looking woman, went wearily along with a child in one arm and a looking glass in the other.”

These were typical scenes among Protestant and Catholic refugees when evictions started by the weekend of 16th August.

The Northern Whig of Tuesday 20th reported “by the early hours of Monday and Tuesday the violence was pursued with “…intensified recklessness and cruelty.” On Monday morning mill workers male and female attempting to go to work around Barrack Street and North Street, were injured, many very seriously after being attacked and many others had to be brought to work with police escorts

The affected districts – Millfield, Browns Square, Smithfield, The Pound, Durham Street, Sandy Row, Falls and Shankill – became centres of make-shift barricades, rioting and gun battles between loyalists, nationalists and police. Rioting and increasingly gunfire, continued between the two sides on Monday 19th and there were reported 17 very serious cases treated in the General Hospital and 60 at the extern department. One man died from a sword wound inflicted by a policeman, when the mobs were being charged. A police officer named Joseph Morton, from Thurles, Tipperary, was shot dead by one of the rioters in Norfolk Street, whilst searching for arms.

The Battle of Brick Fields

The London Evening Standard reported that Saturday’s conditions deteriorated rapidly. Military and police reinforcements were drafted in from Dublin, Dundalk, Antrim and Down. The worst riot occurred at 6pm on Saturday between Shankill and Falls on large open space ground known as Brick Fields, involving several thousand on each side. The mounted military were ordered to charge with ‘raised sabres’ and foot soldiers and police ordered to advance with ‘fixed bayonets’ and form ranks of defensive lines between the protagonists. It took great efforts by the military to finally take control but not until very large numbers of Catholics and Protestants were injured and some very seriously. It ended up involving thousands from each side, when, “…stones fell like hail for a considerable time…” With the scene resembling something more like the battle of Yorke’s Drift their reporter wrote in typically Victorian literary theatricality, “the belligerents were very numerous on both sides, and they fought with a recklessness, and persistency that was most wonderful.”

The Shankill Day of Drunkenness and Sectarian Delirium

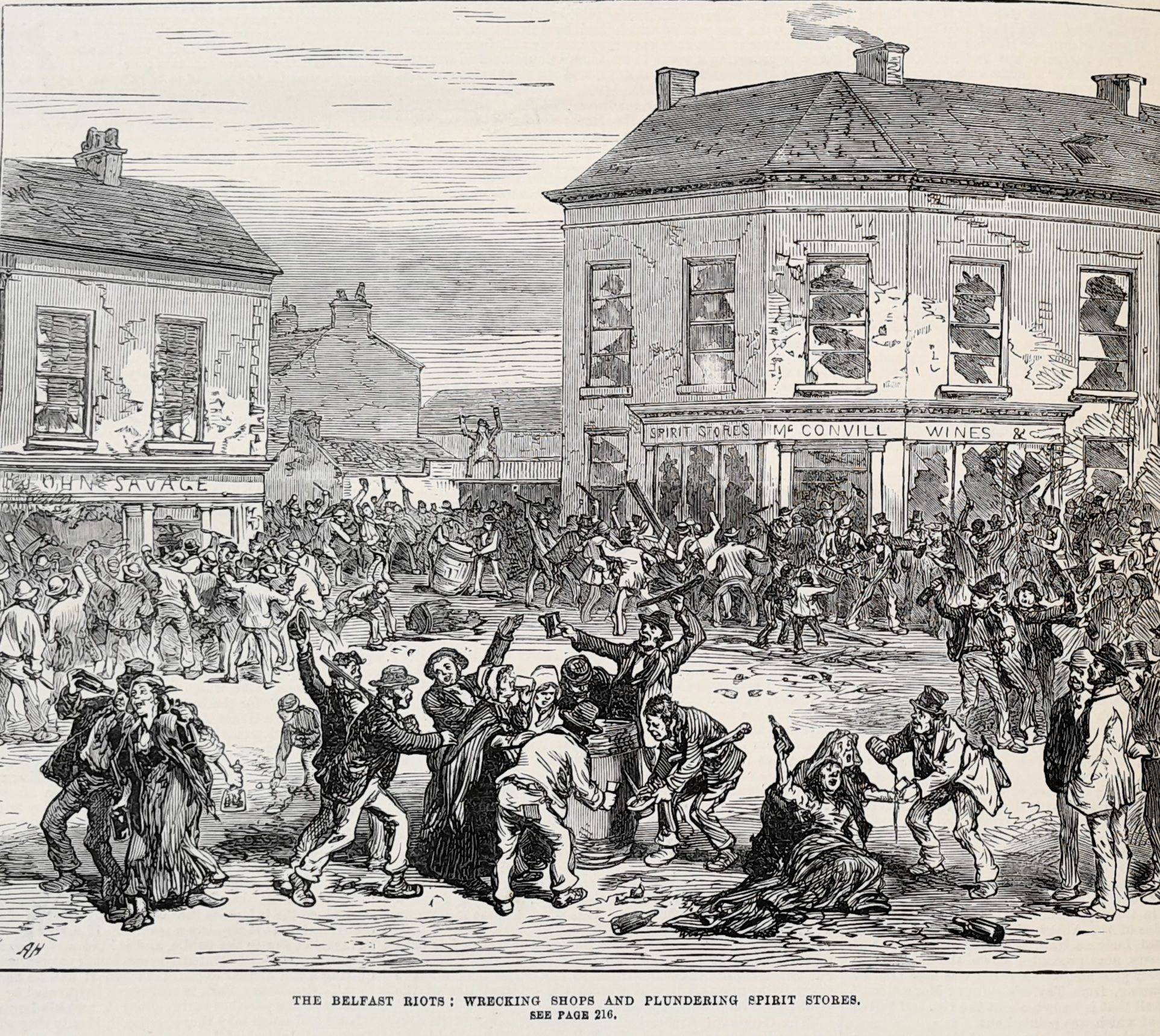

The London Illustrated News reported the infamous Shankill Day of Drunkenness on

Monday 19th August.

“About four o’clock in the afternoon on the Shankill Road, nearly 5,000 men, women and boys were assembled, cheering, shouting and cursing the Pope.” The men dug up the stones of the pavement, while the women and children piled them in small heaps ready for offensive use. The Roman Catholic party did not come forward, as was apparently expected, for another battle, and the Orangemen expended their fury in an attack on the public houses and other shops owned by Catholics. The windows were smashed, the doors burst open, and the premises sacked; barrels of wine, spirits and beer, with hundreds of bottles, were brought out into the open street, and the liquor was speedily drunk, adding fearfully to the prevailing madness. The police tried to disperse the mob, and, having charged with fixed bayonets, were repulsed and forced to retreat a short distance. They turned and fired, two of the rioters were shot, and one soon died of his wound. The soldiers, 4th Royal Dragoons and 78th Highlanders, arrived and took possession of the ground.”

Contemporary Etching based on artist drawings from the Illustrated London News, showing Loyalists and Orangemen looting Catholic owned bars and spirit grocers, Shankill Rd. Monday 19th August

The Dublin Daily Express and other press covering events of Tuesday 20th reported countless confrontations between mobs in town. Of the Shankill evictions it stating,

“The houses on the Shankill Rd have been almost completely gutted; the mobs, not content with removing the furniture, set fire to it in the streets. Many of the inhabitants had to fly for their lives, and during the day hundreds of carts were employed in removing furniture, and the sights of women and children crying through the streets were heart-rendering in the extreme.”

All the schools in town were shut and a few mills only were at work for safety fears of workers, many of whom had been attacked and viciously beaten. Earl Street School in the Docks area, was wrecked and every window smashed and Catholic chapels attacked and vandalised. In town countless shops and businesses remain closed; losses estimated at £100,000.

The London Illustrated News and other accounts including the London Times reporting on the week’s events wrote, “Civil war still rages at Belfast.” Of 30 casualties treated at hospital, injuries included bullet wounds, sword wounds, amputations, extractions, including women and children among the maimed.

“And no wonder, for the women are among the fiercest of the rioters. While the two hostile mobs meet on their battle ground, the women on each side provide supplies of ammunition by piling stones, and excite their champions by taunts, shrieks and imprecations.”

It added: “The poor Catholics of Sandy Row and other quarters exposed to orange violence had been driven to fly from their homes, losing their furniture and household stores, which were destroyed or plundered in their absence.”

At the early part of the second week about 100 rioters were arrested and charged before the courts. For most of the second week all public bars were ordered to be closed by the magistrates and sales of arms were strictly forbidden. Several rioters were also shot dead or killed by sword or bayonet during mounted charges by police, soldiers, dragoons and highlanders drafted into the town as reinforcements.

The Newsletter on Friday 16th, revealed their bizarre interpretation of the repeal of the Party Procession’s Act for unionists and the Orange Order. Despite the new freedoms of the Parades and Processions Act, the Orange Order believed it had a right to object to “treasonable processions” which are ‘disloyal’ to the Crown and when clearly nationalist and anti-Union in their beliefs with flags and symbols when in processions should not have the same privileges enjoyed under that Act, as Orangemen and Unionists. It stated of the Hannahstown processionists,

“The harp without the crown was a common device, and advocates of equal professional rights, will scarcely assert that a seditious emblem ought to receive the same amount of protection as a loyal one, or any protection at all. Liberal 'and enlightened Conservatism' may see to object is to be intolerant: but loyal men will object for all that, even though the device was displayed by a gathering which was calculated to bring contempt on the capital of Ulster.”

The Newsletter also objected to the procession holding French tricolours and displaying mottos recommending friendly feeling with America, “…meaning the Fenian Irish in America…” and banners stating “God Save Ireland”. They described Home Rule and other nationalist aspirations expressed at Hannahstown, as futile “political phantoms.”

“…the Roman Catholics have a right to proceed where they please, provided they do not select such places as are almost exclusively inhabited by Protestants, and thereby calculated to give unnecessary offence to Protestants…It was in the highest degree indiscreet of them to have selected Carlisle Circus as their rendezvous point… because that is a great Protestant Quarter; and Protestants…cannot be expected to look on indifferently at emblems which they consider seditious, and calculated to degrade the authority of the Sovereign of Great Britain and Ireland.”

The End of the Riots and Aftermath

The violence eventually fizzled out by Thursday 22 and almost entirely by Saturday 24 August. A combination of collective exhaustion, days of heavy rains brought them to an end. About 1,000 houses were damaged; enormous levels of destruction to property. Hundreds of persons injured, many seriously, with a small number of fatalities; large numbers intimidated from their homes and hundreds out of work. Hundreds of rounds of of fire exchanged.

On August 24 a series of letters were published in the Northern Whig from ‘Belfast and Ulster Presbyterians’ highly critical of Rev Hugh Hanna, his speeches and conduct in advance of the Hannahstown procession. He was ultimately accepted as being the chief architect of the seven-day civil war in Belfast. The following letter is an excellent example:

“Something must be done to show in what light his conduct is regarded by nearly all Presbyterians. That a Christian Minister should habitually indulge in language of contempt and suspicion towards the great majority of his countrymen is sufficiently shocking… But when the same gentleman – at a time when the town was at peace after his own party had held their celebrations without the slightest disturbance – summons thousands of people to prevent another party from meeting peaceably to have their procession, and thereby inaugurates a carnival of riot, anarchy, plunder and blood shed, it becomes the absolute duty of his co-religionists to express their abhorrence of such conduct.” A Presbyterian, (21st August ,1872).

On August 16, The Ulster Examiner and Northern Star concluded: “The Orange society, is a worthless, meaningless, and defiant threat to everything Irish and everything Catholic. Orangemen would crush us if they dare; they would grind us if they had the power, but they have not. The assembly at Hannahstown proclaims to the world that the Catholics of Ulster are able to hold their own… We are willing and anxious to live at peace with our neighbours, but we will no longer tamely submit to insult, but will resent it.”

©Brendan Muldoon June 2023