IN her latest novel, Yellowface, released in May 2023, following on from her 2022 Booktok smash hit and bestseller Babel, Marshall scholar, and multi-award-winning author Rebecca F. Kuang exchanges transfixing dark academia for satirical literary fiction soaked in cynicism.

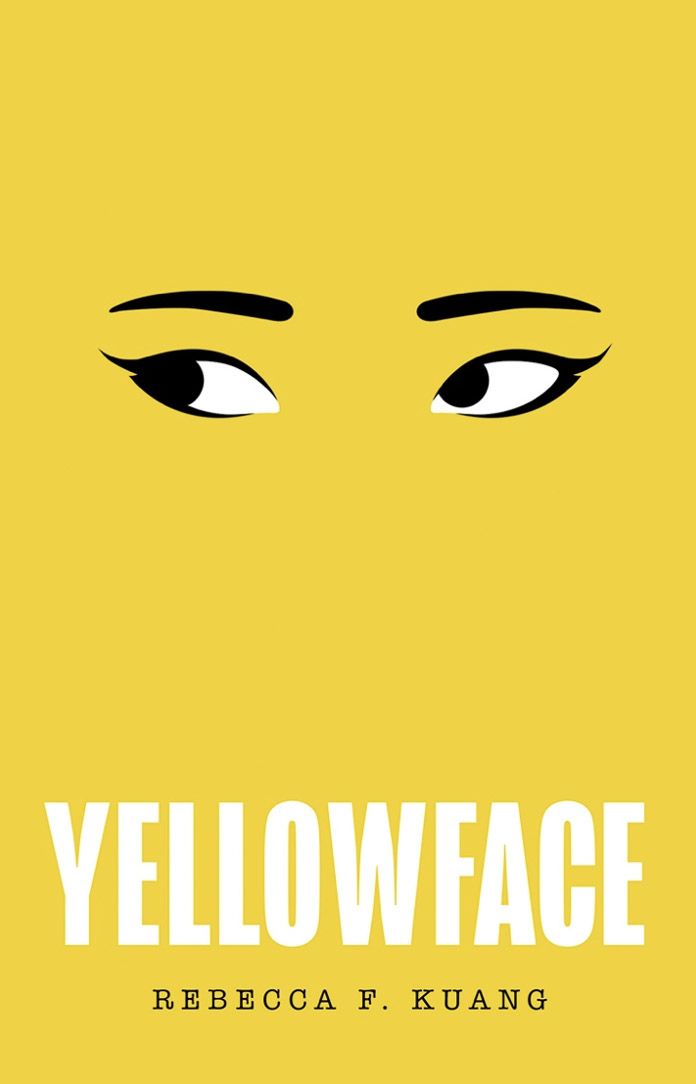

A diasporic writer, Kuang launches a scathing critique of a predominately white, performative publishing industry that distils racial and ethnic identities down in the process of commodification. The eye-catchingly yellow book cover, with its artistic rendering of what the Western world has long termed “almond-shaped eyes”, symbolically represents the industry’s commercialisation of Asian diaspora stories; the repackaging of marginalised people’s experiences for consumers – stripping away any individuality.

Kuang’s disillusioned floundering writer narrator, white “brown-eyed, brown-haired June Hayward, from Philly”, bitterly asserts that what is deemed “exotic”, ergo marketable, is “in”. In the shadow of her fair-weather friend Athena Liu, an acclaimed, adored Chinese-American writer, June’s ignorance and jealousy festers further.

Alongside Athena, described as “a beautiful, Yale-educated, international, ambiguously queer woman of color”, June feels entirely inadequate; unable to compete with a “diverse” writer that the industry “lavishes all its money and resources on”. June believes that Athena’s continual success is a certainty, whereas hers is an impossibility…

… or so she believes until Athena unexpectedly dies in a “freak accident”, leaving behind an unpublished manuscript ripe for the taking: a novel about the Chinese Labour Corps’ harrowing experiences of wartime and discrimination on the Allied Front during the First World War. The unfinished project exemplifies “awards bait” that might attract “commercial” and “upmarket” readers.

Following an extensive editing process that ensures an “accessible”, “universally relatable story”, then subsequently “going to auction, negotiating deals, fielding calls from potential editors, [and] choosing a publisher”, the newly renamed, ethnically ambiguous Juniper Song (courtesy of her publicity team’s decision to position her as “worldly”) eventually publishes The Last Front to critical acclaim.

However delicious the fruits of her ‘labour’ initially taste, she soon finds herself choking on them. Rumours of plagiarism and vitriolic criticism regarding cultural inauthenticity begin to circulate across social media platforms

From awards nominations, to film rights negotiations for Hollywood adaptations that could potentially star British heart-throbs à la Harry Styles/ Tom Holland, along with becoming a New York Times bestseller, “Juniper” seemingly achieves her life’s ambition of stardom: “I’ve made it. […] I’m living Athena’s life. I’m experiencing publishing the way it’s supposed to work. I’ve broken through that glass ceiling. I have everything I ever wanted – and it tastes just as delicious as I always imagined.”. Kuang’s novel presents cynical, thought-provoking discourse

However delicious the fruits of her ‘labour’ initially taste, she soon finds herself choking on them. Rumours of plagiarism and vitriolic criticism regarding cultural inauthenticity begin to circulate across social media platforms, e.g. YouTube, Reddit, TikTok and in particular, Twitter – the “realm that the social economy of publishing exists on” where a writer can be both celebrated and butchered.

Like a “snowball” rolling down an impossibly steep hill, the escalating scandal ceaselessly builds momentum and size. Protective of her newfound success, June’s hubris knows no bounds, as taking the moral high-ground, she wonders why the novel’s true authorship matters “as much as the fact that, without [her], the book might never [have seen] the light of day…”.

Kuang’s novel presents cynical, thought-provoking discourse on the ethics of cultural appropriation and representation in the contemporary literary world.

The ethical quandary of fictionalising traumatic experiences related to the marginalised is evidently familiar to Kuang. Her Hugo, Nebula, Locus, and World Fantasy Award nominated Poppy War trilogy was inspired by her own family’s history in China during the turbulent 20th century.

In Yellowface, Goodreads users and critics alike begin to question June’s right to publish stories she has no cultural connection to; slamming The Last Front as yet another “white saviour story” that capitalises on the tumultuous, painful history of a particular epoch to create “entertaining set piece[s] for white entertainment”.

The novel bluntly asks us to ponder these questions: unless writers directly experienced/ personally identify with their work’s real-world subject matter, do they have the right to publish and profit from it? Might such writing blindly perpetuate stereotypes and widespread ignorance, and therefore be unwittingly racist? Even if they don’t possess a personal connection, what if the project is written through painstaking research with complete respect and integrity?

Ultimately, is writing no more than an act of thievery?

Yellowface is published by The Borough Press (RRP £14.99)