WE are an arrogant lot, us humans. When we as a race learn something new – like evolution or how the earth is round – we seem to pretend we always knew it.

The facts of life that we know today seem to us to be so obvious that we can’t even comprehend how anyone could not have known them. But up until a century and a half ago, there was one aspect of bird life that remained a worldwide mystery despite the fact that today it’s as plain as the nose on your face – migration.

We just didn’t know why some birds disappeared at various times of the year, while others arrived. That they travelled to other parts of the world because of the weather might to us seem so simple that’s it’s a given, but in years gone by it was simply inconceivable. No-one even suggested it because it was beyond the realm of possibility.

Most people thought the vanishing birds hibernated. Aristotle believed swallows hibernated in crevices in trees and that summer birds changed their plumage in winter to become totally different birds. And they said he was smart? A Swedish priest in the 16th century had a theory that persisted until the late 1800s that swallows hibernated in mud at the bottom of rivers and lakes.

But famous British physicist Charles Morton, a genius whose books are still on university curriculums, claimed the first prize for imagination – he believed the vanishing birds flew off to the moon.

It seems farcical to us now but the unquestionable truths of today were not yet conceived. It was generally believed that other planets must be inhabited and no-one knew there was no vital oxygen between them.

But the first dagger to the heart of those theories was delivered, almost literally, in 1822 in the form of a wounded stork in Germany. It was shot by a hunter and when he picked it up, he discovered it had a huge spear sticking out of its neck. When experts examined the wood, they determined it came from Africa. And so the old theories began to unravel. The stork had spent the German winter in Africa. That famous stuffed stork – spear and all – is still on display in a museum in Germany.

The story of bird migration is still a work in progress, however. There is so much we still don’t know, but we’re getting new data all the time. Not from zoologists and qualified ornithologists, but from an armchair army of amateur birdwatchers.

One American expert spent lockdown writing a book about them, which has just been published. Rebecca Heisman’s ‘Flight Paths’ is one of countless books on the subject, but the only one which gives the credit where it is due – to those unsung heroes who are harnessing the latest technology to track these birds on their journeys.

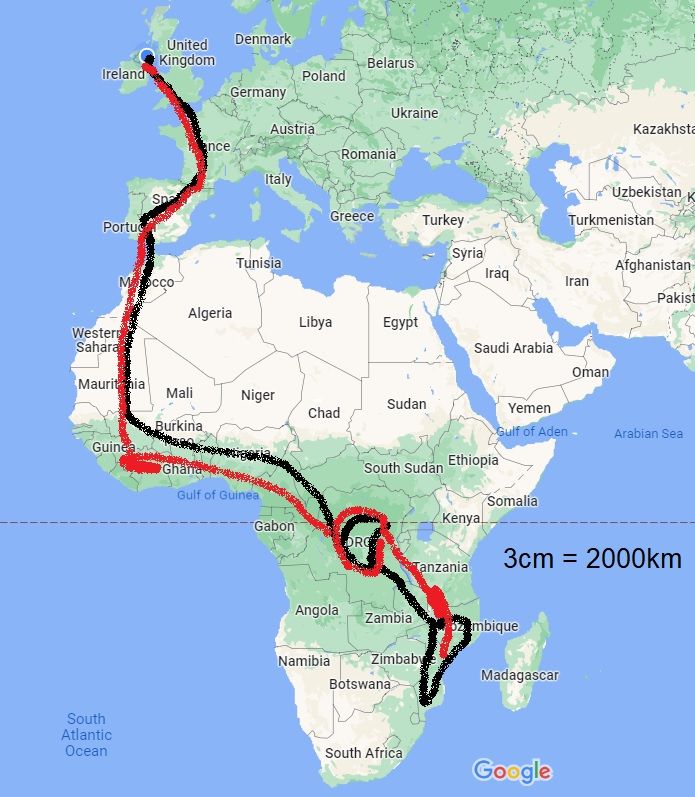

2023 was the year when Dúlra fully understood how so many people are fixated by migratory birds. He’s got the bug. And it’s the bird that graces the cover of Rebecca’s book that did it for him. The swift, gabhlán gaoithe in Irish, is one of the most incredible migrants of them all. It only touches ground to breed and it even sleeps in the air. And it spends just 100 days in our skies each summer.This year Dúlra has been transfixed by them. Their powerful aerodynamic bodies skim through the air like fighter jets and their screaming calls can be just as loud. To that army of enthusiasts who are helping solve the migration conundrum you can add Antrim’s Mark Smyth, who single-handedly tracked the swifts breeding on his gable wall to Mozambique in southern Africa.

But each year Belfast loses more and more of these precious birds. As homes are repaired, the crevices that they use for nests disappear. They are vanishing before our eyes and we don’t seem to care. The Andersonstown of Dúlra’s youth had swifts nesting on every end house; today there are just a few pairs hanging on. Dúlra’s swift boxes – fitted by Mark – weren’t occupied this year, despite the round-the-clock recorded calls blasting out to attract them.

He thinks he knows why – he didn’t have the amplifier on full whack in case he annoyed the neighbours. He’s warning them now – next year they're going to need earplugs!

If you’ve seen or photographed anything interesting, or have any nature questions, you can text Dúlra on 07801 414804.