Picture this scenario: you’re walking down the Falls Road and in the distance you see an old friend from the past approach. You continue to get closer and then, when you are face-to-face, your friend walks by without acknowledging you.

What would your feelings be on seeing an old friend? Most likely good feelings would arise..Then what feelings arise when your friend walks past and blanks you with no acknowledgement whatsoever? No doubt, internal talk would arise? Did I do something wrong? Did I offend him?

Then a few weeks later you meet again. How would you feel this time? This time the old pal acknowledges you and you discover he didn’t notice you that last day as he was consumed with sadness at news he had just received. How would you feel now?

Mindfulness of feelings is noticing that a feeling is no more than a feeling. We discover how feelings can be wrong.

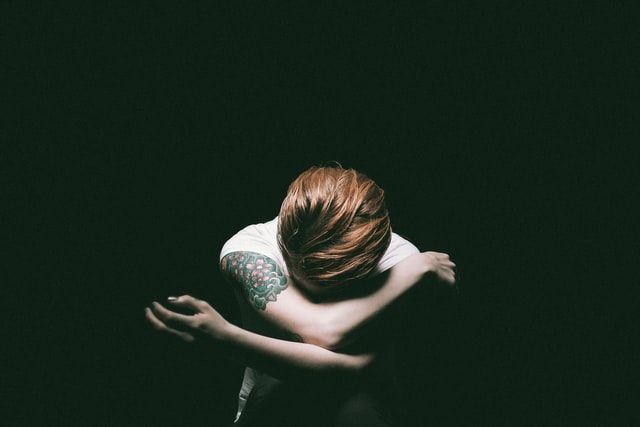

Mindfulness is about coming to the realisation that feelings are not good or bad, they are just feelings. It is the label that we give them that affects the way we experience them. When feelings arise, mindfulness teaches us to accept them, without judging or trying to change them.

Most people who come to mindfulness are looking for respite from what is sometimes called 'monkey mind'— the perpetual, hyperactive (and often self-destructive) whirl of thoughts and feelings everyone undergoes.

But the truth is that mindfulness does not eradicate mental and emotional turmoil. Rather, it cultivates the space and gentleness that allow us intimacy with our experiences so that we can relate quite differently to our cascade of emotions and thoughts. That different relationship is where freedom lies.

Lovely pic of HH #DalaiLama & HE Kundeling Tatsak with Ven #Panchen #Otrul #Rinpoche #Cavan #Buddhism @Jampa_Ling :) pic.twitter.com/MT6Arz1n3L

— Jampa Ling (@Jampa_Ling) February 10, 2016

Here is a practice that I was taught by a great Tibetan Buddhist teacher, who was my first teacher and introduced me to Buddhism and mindfulness practice. His name is Panchen Otrul Rinpoche from Tibet and he resides six months of the year in the lovely County Leitrim.

I met Rinpoche some thirty years ago as I began my pursuit for peace of mind. The first time I met him, I had arrived at the monastery early, and there was no one about. It was a beautiful sunny day so I sat and rested on a sun lounger where I fell asleep. I was awoken by the purring and pawing of his cat on my chest. As I opened my eyes, I saw the cat’s beautiful black and white face and behind the head of the cat was Rinpoche’s radiant, smiling face.

He welcomed me and invited me in for tea. I explained to him my emotional roller coaster and how I was always at the mercy of my thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Rinpoche listened to my plight and gave me this mindfulness lesson to practice.

RAIN is an acronym for a practice specifically geared to ease emotional confusion and suffering. When a negative or thorny feeling comes up, we pause, remember the four steps cued by the letters, and begin to pay attention in a new way.

R — Recognize: It is impossible to deal with an emotion—to be resilient in the face of difficulty—unless we acknowledge that we’re experiencing it. So the first step is simply to notice what is coming up. Suppose you’ve had a conversation with a friend that leaves you feeling queasy or agitated. You don’t try to push away or ignore your discomfort. Instead, you look more closely. Or, you might say to yourself, "this feels like anger". Then this might be followed quickly by another thought: and I notice I am judging myself for being angry.

A — Acknowledge: The second step is an extension of the first—you accept the feeling and allow it to be there. To put it another way, you give yourself permission to feel it. You remind yourself that you don’t have the power to successfully declare, “I shouldn’t have such hateful feelings about a friend,” or “I’ve got to be less sensitive.” Imagine each thought and emotion as a visitor knocking at the door of your house. The thoughts don’t live there; you can greet them, acknowledge them, and watch them go. Rather than trying to dismiss anger and self-judgment as “bad” or “wrong,” simply rename them as “painful.” This is the entry into self-compassion—you can see your thoughts and emotions arise and create space for them even if they are uncomfortable. You don’t take hold of your anger and fixate on it, nor do you treat it as an enemy to be suppressed. It can simply be.

I — Investigate: Now you begin to ask questions and explore your emotions, with a sense of openness and curiosity. This feels quite different from when we are fuelled by obsessiveness or by a desire for answers or blame. When we’re caught up in a reaction, it’s easy to fixate on the trigger and say to ourselves, “I’m so mad at so-and-so that I’m going to tell everyone what he did and destroy him!” rather than examining the emotion itself. There is so much freedom in allowing ourselves to cultivate curiosity and move closer to a feeling, rather than away from it. We might explore how the feeling manifests itself in our bodies and also look at what the feeling contains. Many strong emotions are actually intricate tapestries woven of various strands. Anger, for example, commonly includes moments of sadness, helplessness, and fear.

N — Non-identify: In the final step of RAIN, we consciously avoid being defined by a particular feeling, even as we may engage with it. Feeling angry with a particular person, in a particular conversation, about a particular situation is very different from telling yourself, “I am an angry person and always will be.” You permit yourself to see your own anger, your own fear, your own resentment—whatever is there—and instead of spiraling down into judgment (“I’m such a terrible person”), you make a gentle observation, something like, “Oh. This is a state of suffering.”

We cannot will what thoughts and feelings arise in us. But we can recognize them as they are—sometimes recurring, sometimes frustrating, sometimes filled with fantasy, many times painful, always changing. By allowing ourselves this simple recognition, we begin to accept that we will never be able to control our experiences, but that we can transform our relationship to them. This changes everything.