Hero. n. A person who is admired for their courage, outstanding achievements or noble qualities.

APPARENTLY Dennis Hutchings was a hero. A “great man,” according to former Veterans Minister Johnny Mercer, speaking at his funeral, who was being laid to rest “by a grateful nation”.

There’s been a hell of a lot of oul’ guff talked about what happened in that field in County Tyrone in 1974 and afterwards, mostly by people who haven’t taken the time to apprise themselves of the facts of the matter. So, herewith a reader-friendly overview of the killing of John Pat Cunningham and the meaning of ‘hero’.

Immediately after the shooting, Hutchings, who was leader of the patrol involved in the killing, gave a series of “no comment’ interviews to investigators (also known as colleagues). In other words, he had been in charge of a unit which had been responsible for shooting a young man with learning difficulties in the back and he refused to say what happened. Might hiding the facts about that be described as “a noble quality”? Clearly in England it might. And in parts of our own loyal province, where prominent unionists have been tripping over themselves to pay tribute to a man who, it seems, single-handedly averted a civil war.

Questioned a year later, Hutchings continued to reply “no comment” when asked what happened in the field at Benburb. And that was that – until the past came back to order him to attention.

Faced by m’learned friends in court this year, Hutchings continued to rack up the “outstanding achievements” that are the dictionary definition of a hero. An Irish Times report reads: “A British Army veteran charged in relation to the fatal shooting of a man with learning difficulties does not accept that he fired any shots, his trial has heard.” The report continued: “In relation to the fatal shooting on June 15th, 1974, a defence barrister said Hutchings accepted he was in the field where the incident happened, but nothing else.”

So there sat the brave old soldier in the dock, his medals pinned proudly to his chest, lying through his teeth about the slaughter of a vulnerable young man whose trousers were held up with baling twine and who was wearing odd socks when he fled terrified from Hutchings and his chums. Is that an “outstanding achievement” or is it a “noble quality”. Both, probably, says the DUP.

So up to now and over the course of 47 years Hutchings has refused to say a dickybird about what he saw in the field when John Pat was cut down. And now as he sits in court with the cheers of a grateful nation ringing in his ears he has said he didn’t fire any shots. Which kind of suggests that Hutchings isn’t the sharpest bayonet in the barrack room since it was established when his rifle was taken from him all those years ago that he had in fact fired three shots.

Hutchings therefore sounded the retreat, as this Belfast Telegraph report shows: “Dennnis Hutchings is to claim he fired only warning shots in the direction of a vulnerable young man while on duty with the army in County Tyrone in 1974.”

So, to recap on Hutchings’ contribution over nearly half a century to the cause of truth and justice:

“No comment.”

“Didn’t fire any shots.”

“Fired warning shots.”

Easy to see why the DUP and the UUP were represented at his funeral alongside the Rolling Thunder veterans’ motorbike club, whose members are a bit like Hell’s Angels, only they smell of Vicks and talcum powder instead of Jack Daniels and weed.

Right, what have we established so far? Well, we know that Hutchings refused to say what he knew about what happened in that field. We know that he lied his ging-gangs off about having fired no shots. And we know that his claim to have fired shots in the air is to be considered in the light of the fact that he’s a proven dissembler and liar. So that’s the dictionary definitions of “outstanding achievements” and “noble qualities” taken care of.

What about “A person who is admired for their courage”? Let’s see now…

Five shots were fired at John Pat that day. Or, if we take the word of proven liar and concealer-of-truth Hutchings, at him or over his head. The gentle, snowy-haired grandad, known before his date with the dock as Soldier A, fired three shots. A colleague, Soldier B, fired three shots. And of course Hutchings claims he fired his shots in the air, which means that he has pointed the finger of blame firmly in the direction of his old army chum, who fired the other two unaccounted-for shots. And does that old soldier admit that, yes, I shot a vulnerable young man in the back as he was running away from me and posing absolutely no danger? Well, no, actually, he doesn’t, for the very simple reason that he is dead. And, so, going by the evidence given by Hutchings, it was Soldier B what done it and he’s not around to say whether the proven liar is lying again.

So, while Hutchings stabbed his old army chum in the back, he definitely didn’t shoot anybody in the back because he fired his shots in the air. It was his oul’ mate who did the foul deed, according to Hutchings. Is chucking your deceased chum under a Chieftain tank something that renders Hutchings “admired for his courage”? In Tory England and unionist Ulster it is. But what Soldier B’s family think about that brave veteran getting hung out to dry is a question that hasn’t yet been asked, much less answered.

Which brings us finally the question of maths. John Pat Cunningham suffered three wounds: one to the back, one to the shoulder and one to the hand. Soldier B, the guilty man according to – all together now – Dennis Hutchings, fired two shots. Hutchings, according to liar Hutchings, fired his three shots in the air. So how come John Pat suffered three injuries? It is possible, naturally, that a single bullet can cause two wounds, but that theory will now never be stress-tested in court. And all we are left with is the evidence of Dennis Hutchings. Who claimed he never fired any shots. And then said he did. In the air. Who repeatedly said “no comment” when asked what happened to an innocent young man lying dead in a field with a bullet in his back.

All hail the hero.

Skin and tin in the bin

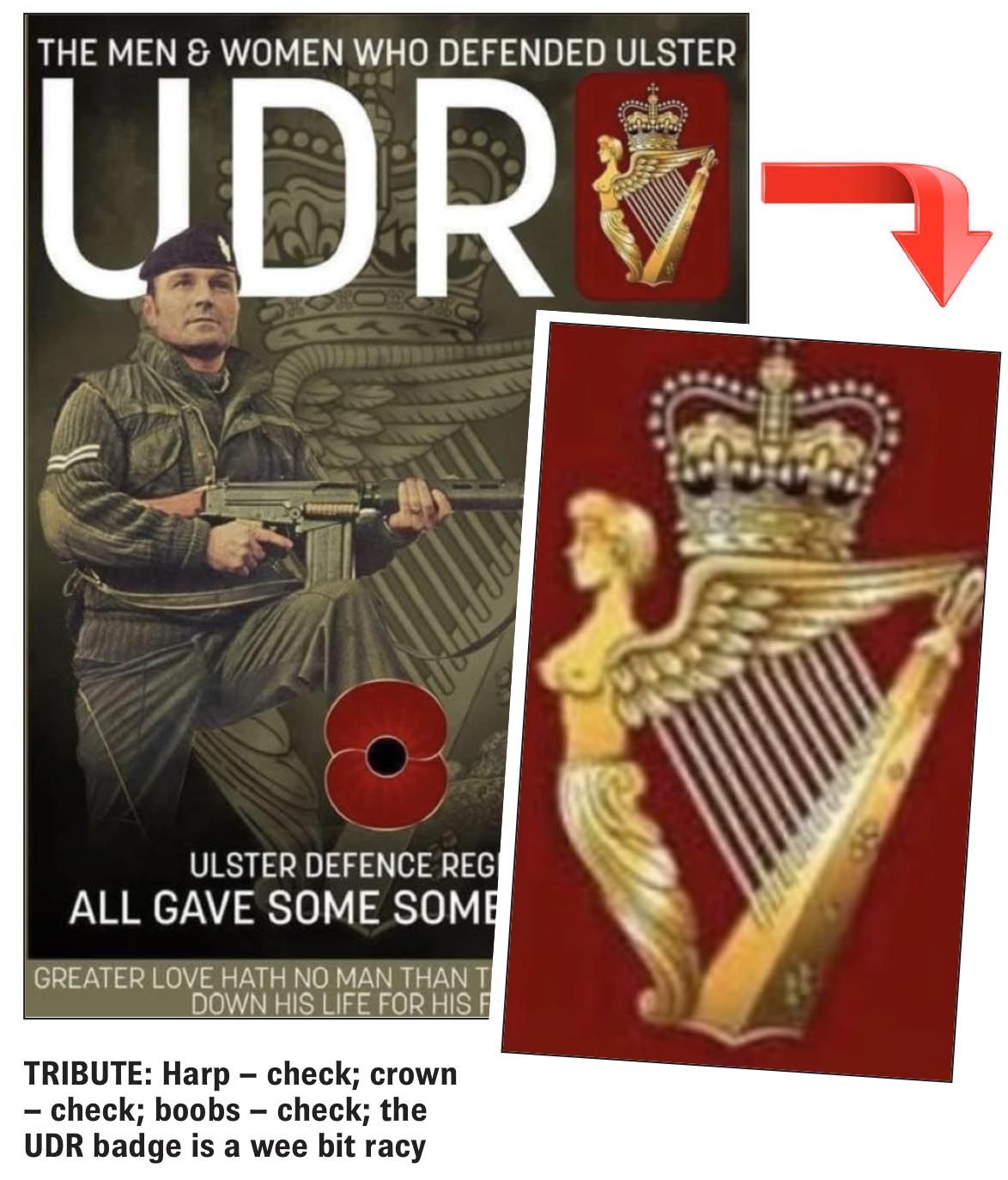

CHIP shop fan and great outdoorsman Sammy Wilson posted this stirring tribute to the men and women of the UDR in Remembrance Week. And while, of course, Squinter’s immediate and primary reaction was one of great joy and pride, a little bulb at the back of his head flickered tantalisingly on and off.

It was the rather perky set of boobs on the female figure on the UDR cap badge that set Squinter to thinking and it wasn’t long before he recalled that Sammy hasn’t always been a fan of displaying women’s womanly bits in public, real or metal.

Squinter’s thoughts drifted back to July 2016 when the East Antrim DUP MP, still buzzing from the vote the previous month to leave the European Union, shared with us his thoughts about breasts in public. Responding to an independent review that recommended women MPs be allowed to breast-feed in the House of Commons, Sammy said: “There are plenty of opportunities to do it elsewhere and I don’t think it’s appropriate.” He added that he wasn’t a fan of women feeding their children outside the chamber either, helpfully pointing out it meant “the woman has to expose her breasts in public”. He also described women breastfeeding in public as “voyeuristic”, which suggests rather worryingly he doesn’t know what the word means, but let’s stick to the point.

So let’s see if we’re getting this right, shall we? Real breasts in the House of Commons, not good; tin breasts on Twitter good. Is that about right? Yeah?

Squinter’s advice to Sammy is to show a bit of consistency. Whether they’re skin or tin, if bare breasts are not a good idea in the House of Commons then they’re not a good idea on Norman’s beret. The Bangor DUP councillor who told that hussy Rihanna to get dressed when she was filming a music video half-naked in his field had the right idea.

Because a boob’s a boob, wherever it’s displayed. And, of course, a tit’s a tit.

A sign of the festive times

TO Newtownards, on a mission of such galaxy-bending banality that we shall not trouble posterity with its details.

Lunch in a bijou café, by whose name we shall remain similarly untroubled, where the Christmas music on a loop was covers of festive classics by soul singers. (“Aaaaaaand have yourself a merry little Christmaaa – aaaa – aaas... now-hoooooow” and so on and so forth.) With workmen busying themselves around him erecting decorations and lights, Squinter enjoys a light repast and then rises for the 25-minute drive back to the Big Smoke.

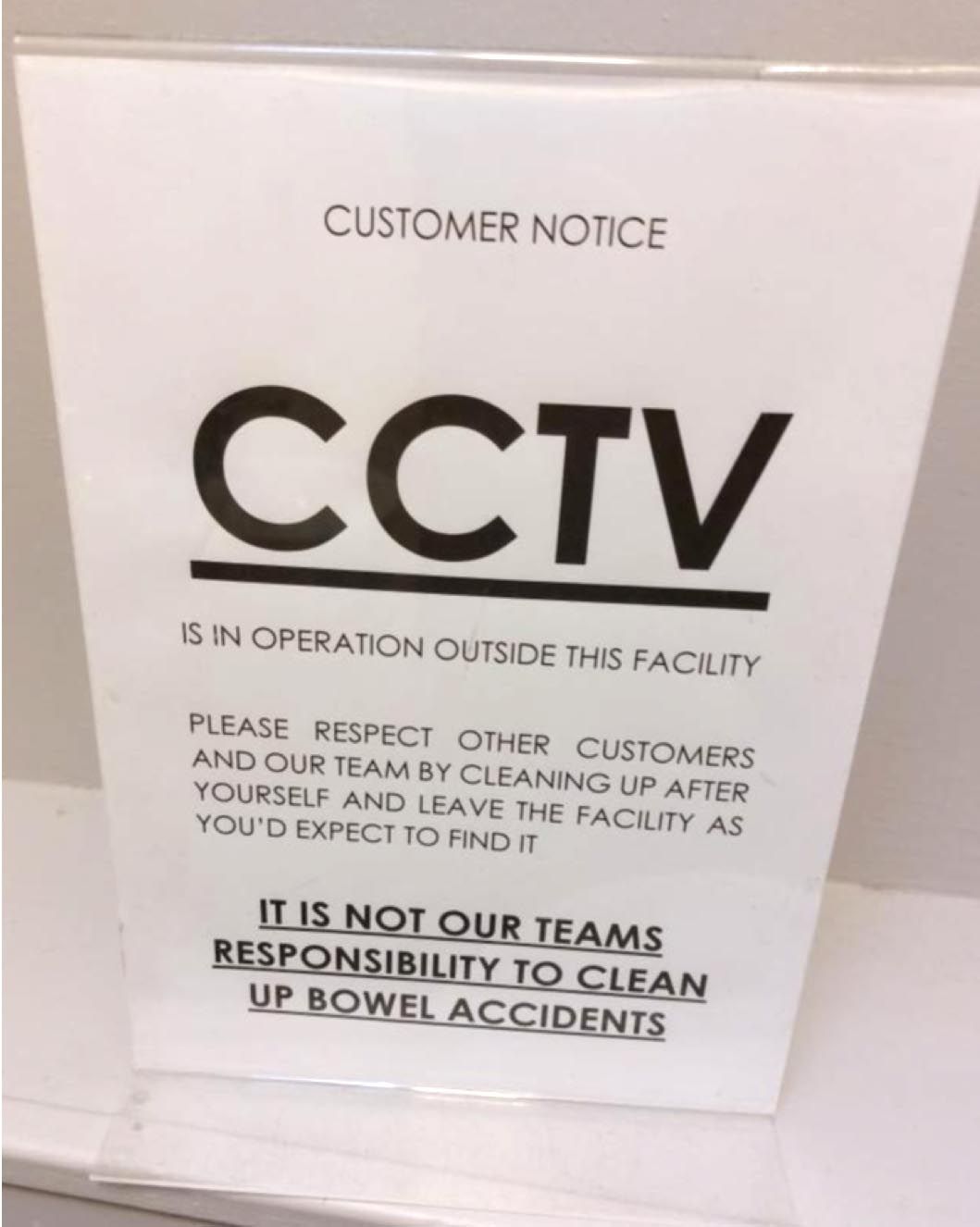

But not before what our American cousins might call a bathroom break. Two stalls, both of them accessible only by a security code supplied by a member of staff, which is kind of odd, particularly because this does not seem like the kind of establishment that might be patronised by the rambunctious.

A quick check and Squinter establishes that there are no paper towels or toilet roll, but what there is is this sign pointing out that you’re being watched while you’re hopping around on one leg waiting for the toilet to be free and that should you happen to fall victim to a ‘bowel accident’ once inside you’d damn better get the power hose and bleach out yourself. As Squinter regards the sign before trying the next cubicle for hand towels and bog roll, he breathes a sigh of relief that he hadn’t been in here before he’d had his lunch. And he hopes that the café isn’t playing ‘I Saw Three Ships’ when he gets back.