THE Great Irish Famine is the most defining period in modern Irish history. Approximately 20 per cent of Ireland’s population was lost in a period of five years from 1845 to 1850, with at least one million deaths in Ireland and one million forced to emigrate. Famine deaths in Ireland may have been as high as 1.5 million.

A critical question and matter of contention was how the English press reported the Irish Famine. English newspaper journalism seemed utterly detached from the stark realities of the sheer scale of the human horrors and appalling suffering occurring throughout Ireland daily during its worst years. The leading English newspaper at the forefront of Famine journalism was the London Times, which believed that the Irish people were largely responsible for that ‘Great Calamity’ and the enormity of their own sufferings and misery.

The London Times was the single most referenced and quoted English newspaper source during the Famine years in the Belfast press and frequently in other contemporary Irish newspapers. It was the most widely circulated newspaper in Britain, dominating all other British newspapers with daily sales of 35,500 in 1848.

Consequently, it had very substantial influence on the British political establishment and on government policy on Irish affairs and wider educated public in Britain. It had a leader column and regular news and commentary almost every week during the Famine years.

Given its political influence it’s been suggested “the Times pressed for a ‘minimalist’ government famine relief policy response by presenting the Irish as undeserving of British support”. The Times certainly held racist views on the indigenous Irish people, describing them as the “laziest people in the face of God’s Earth”.

The London Daily News (January 1847), admonished the Times for its anti-Irishness, racism, hostility against the Irish landlords and the starving Irish poor. It was convinced that the Times was giving any number of reasons, if more were needed, for the support of Daniel O’Connell and Irish nationalists’ calls for the end of the Act of Union and for Irish independence. It stated apprehensively of the Times’s influence and power: “The Times is the Attorney-General of Irish starvation... Never did the followers of Daniel O’Connell utter arguments so directly tending to a separation of the countries as those articles of the Times.”

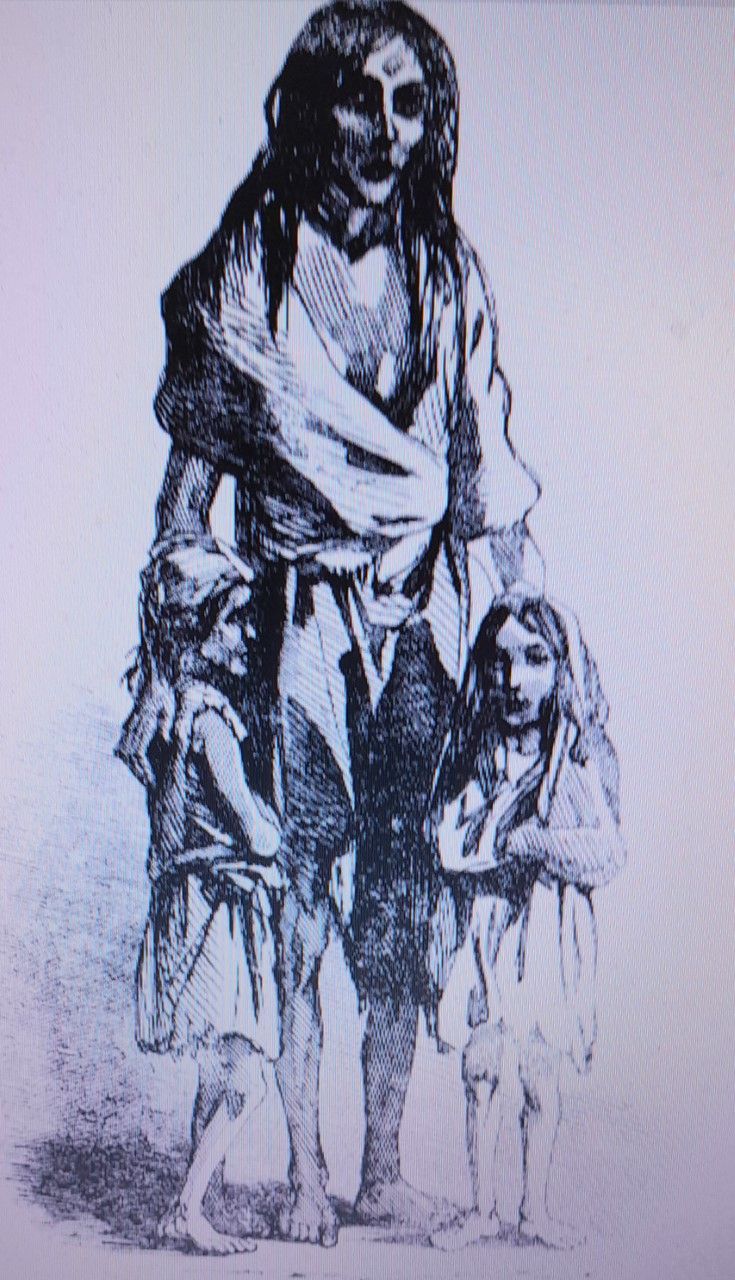

Starving Children searching for potatoes, West Ireland, 1847, Illustrated London News

The Times was scrutinised by Belfast and Irish newspapers generally and controversy or conflict frequently emerged depending on the nature of its commentary on Irish affairs. The News Letter described the Times as “the most able and successful journal in the world”, when commenting on the reports of the Times’ ‘Commissioner’ – its Irish affairs reporter – on September 9, 1845. The nationalist Belfast Vindicator described the Times as “Ireland’s Implacable Enemy” in its edition of February 20, 1847. In marked contrast the liberal Northern Whig said of the Times: “Whatever we may think of the political character of the Times, it is due to that mighty journal to acknowledge that... it is clearly entitled to the high credit of making the rights of the poor paramount over all other considerations.”

It’s “highly significant” that in the same column they share their own confidence in the Times for its “positive influence” on British Government policy and with informing and influencing the wider public in Britain on the Irish situation (September 13, 1845).

In the early years of the Famine, 1845 to 1846, were the regular reports from the Times Commissioner, T.C. Foster, Q.C., who travelled around Ireland reporting his observations and analysis in letters titled ‘The Condition of the People of Ireland’, published regularly by the Times in London and reprinted in many Irish newspapers. The Times’s Commissioner’s overarching belief was that Ireland’s poverty and backwardness could not simply be explained by over-population or dependency on one main food source, but by the inherent laziness and lack of industry and entrepreneurial spirit of the native Irish Celtic people (excepting the settled Ulster Protestant Anglo Saxon plantation population whom he deeply admired). He later wrote to the Times of his despondent views of the inferior, barbarous, lazy uncivilised native Irish. “To grapple with these monster evils is, indeed, a terrible task; but these are the evils with which the government must grapple if it hopes to see Ireland no longer a stumbling block and a difficulty – alike the weakness and the disgrace of the empire.”

In his report of January 13, 1846, he mockingly compared the prosperous, industrious northeast of Ireland with the wretched poverty he witnessed in the provinces in the south and west of Ireland, adding a disparaging criticism of Irish Nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell for the conditions of the peasantry settled on his landed estates in Derrynane in County Kerry. After arriving in Belfast his published letter stated: “I came here from Kerry, in the extreme West of Ireland. In Kerry, on the estates of one of the ‘patriots’ (so-called) of Ireland, and, indeed, generally all over the County, I saw wretched hovels, barefooted women, naked, unemployed children, and men too lazy, too ignorant, too apathetic, and content with discomfort, to either cultivate their land properly, or make themselves dwellings better than cow-houses. There not a tree, nor a hedge, nor a turnip field is to be seen; and the signs of industry are overwhelmed by the evidence of laziness and neglect. Here, in the County Down, under the same law, in the same country, without a single advantage in climate, soil, or opportunity, the houses are well built, clean, and replete with every comfort; the women are well clothed; every boy and every girl is employed and earning money, and every man is fully and profitably occupied.”

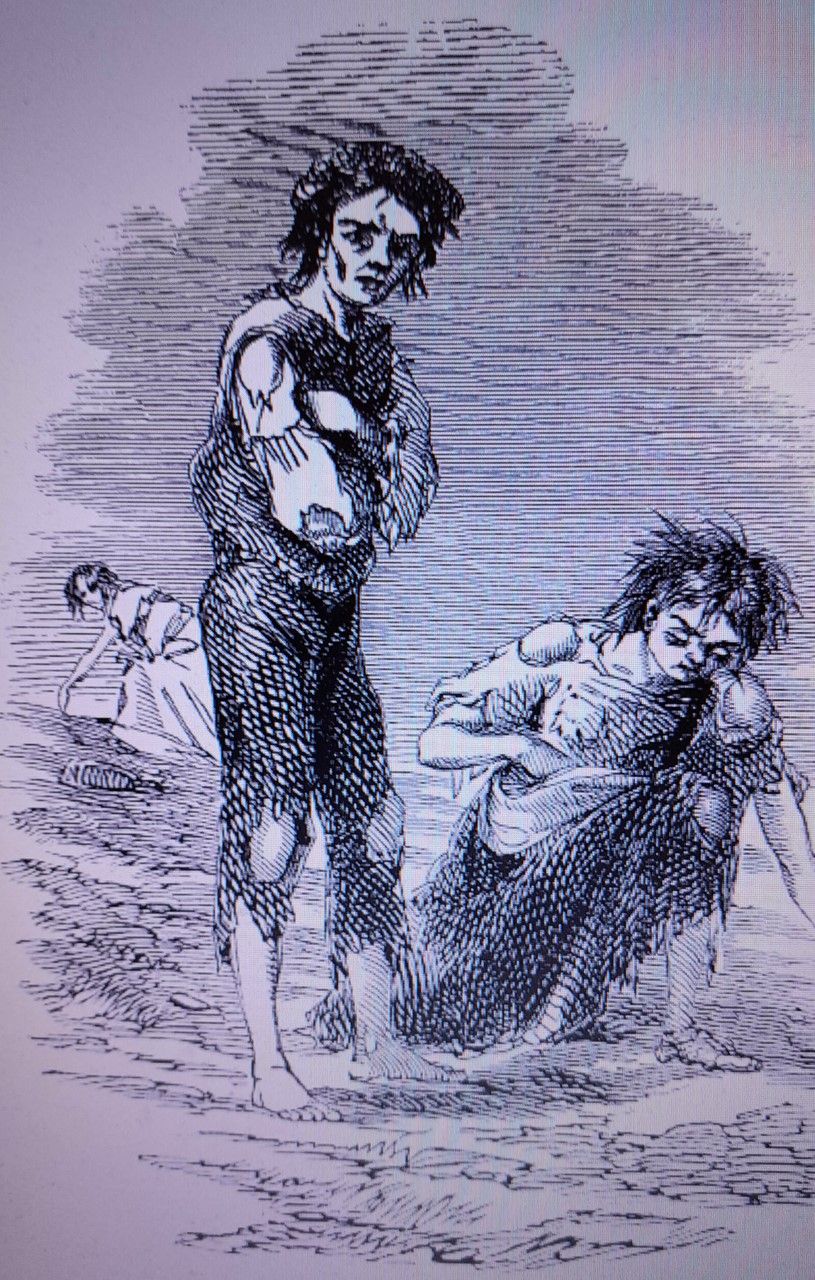

Mother and son digging for potatoes. West Ireland, 1847, Illustrated London News

A storm of controversy followed the piece and it elicited a strong and robust defence of Daniel O’Connell and the peasantry by the Belfast Vindicator and personally by Daniel O’Connell and his son in the nVindicator’s columns, which included extensive supportive letters from the public (January 17, 1846).

The Commissioner’s letters confirmed what the Protestant/Unionist establishment of Ulster and the Orange Order had long felt – that Ulster was a place apart from the rest of Ireland given its history as a settled colonialist society of lowland Scottish and English Protestants. Its distinct provincial identity was characterised by “good habits of industry”, hard work, thrift, business acumen, peace and stability. These things, Ulster Protestants believed, if the columns of the News Letter and Northern Whig were anything to go by, were in stark contrast to the other provinces of Ireland, where poverty, indolence, laziness, lawlessness and backwardness were characteristically widespread among the native Celtic Irish.

The News Letter claimed that the Ulster Plantation was a success story of economic, social and cultural progress. These differences, the Times’ Commissioner believed, were due to the superior moral, cultural and racial superiority of Saxon lowland Scottish and English blood in contrast to the morally and culturally inferior indigenous Celtic Irish. The News Letter believed that the racial differences that accounted for this were not the “core issue”, but the superior religious values of Protestantism and loyalty to the British Crown. The notion of the Protestant ‘Ascendancy’ and Protestant Anglo Saxon ‘superiority’ were central to their core beliefs.

The enormous tragedy emerging during these times of such vitriolic distractions over Ulster Protestant Anglo Saxon ‘superiority’ and native Irish Celtic ‘racial inferiority’ dominating local newspapers columns, instigated by the Times’ Commissioner’s intentional provocation and racist anti-Irish crusade, was that the profound horrors of Ireland’s Great Famine were widely raging and ravaging the rural and urban populations across Ireland at the same time, especially in the south and west with catastrophic effect and overshadowed anything that ever came before.

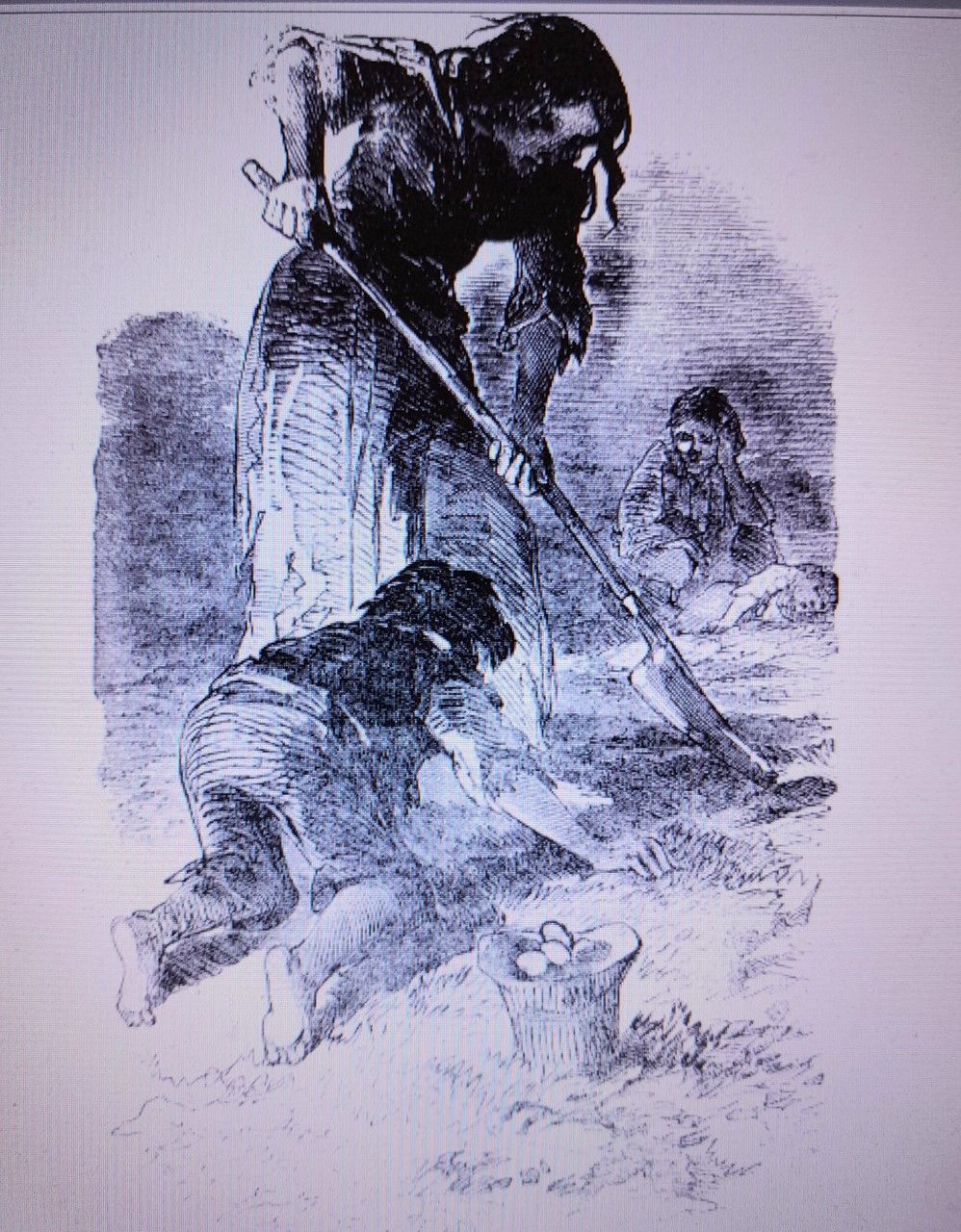

Mother praying before her dying child, West Ireland, 1847, Illustrated London News

The Kerry Evening Post reported that at Kilquane, westward of Dingle, one fifth of the inhabitants had already fallen victim to famine and disease. The body of a poor woman, who died of fever at Lughnacoppul, was, on Friday night, nearly devoured by dogs, the neighbours being afraid of the infection to enter the house. Two children were in the house at the time, one of whom also died of fever, but they were untouched. The body of the woman was so much eaten that they were not able to put her in a coffin; her remains were then collected into a bag. The Westmeath Independent reported: “It has been found necessary to keep watch, during the night, at the Abbey graveyard, Athlone, to prevent the numerous hungry dogs who resort to it, after nightfall, from devouring the dead interred therein. On Monday night, two dogs were shot, one in the act of carrying away the leg and thigh of a man buried the day previous”.

In February 1847, the Belfast Vindicator added further reports. In County Waterford, at Dungarvan, there were 462 families, consisting of 2,303 individuals, on the Duke of Devonshire’s estates, in a state of starvation; 275 families, 1.235 persons, on the estate of the Marquis of Waterford, in a similar situation; 57 families, consisting of 261 persons, on Sir John Power’s Estate; and 272 families, comprising 1,233 individuals, on the estate of John Kelly Esq, of Struncally Castle. Total, 1,066 families, consisting of 5,032 individuals.

All of Ireland was faced with appalling levels of mortality, destitution, hunger, diseases, including dysentery, cholera, and typhus fever, with burials in mass graves for thousands of victims. Workhouses were full to overflowing and, despite efforts from public authorities, private charitable ans benevolent agencies, and emigration, the situation in Ireland was dire. People were eating grass, nettles, even killing and eating their own dogs, or dead dogs they found by the roadside.

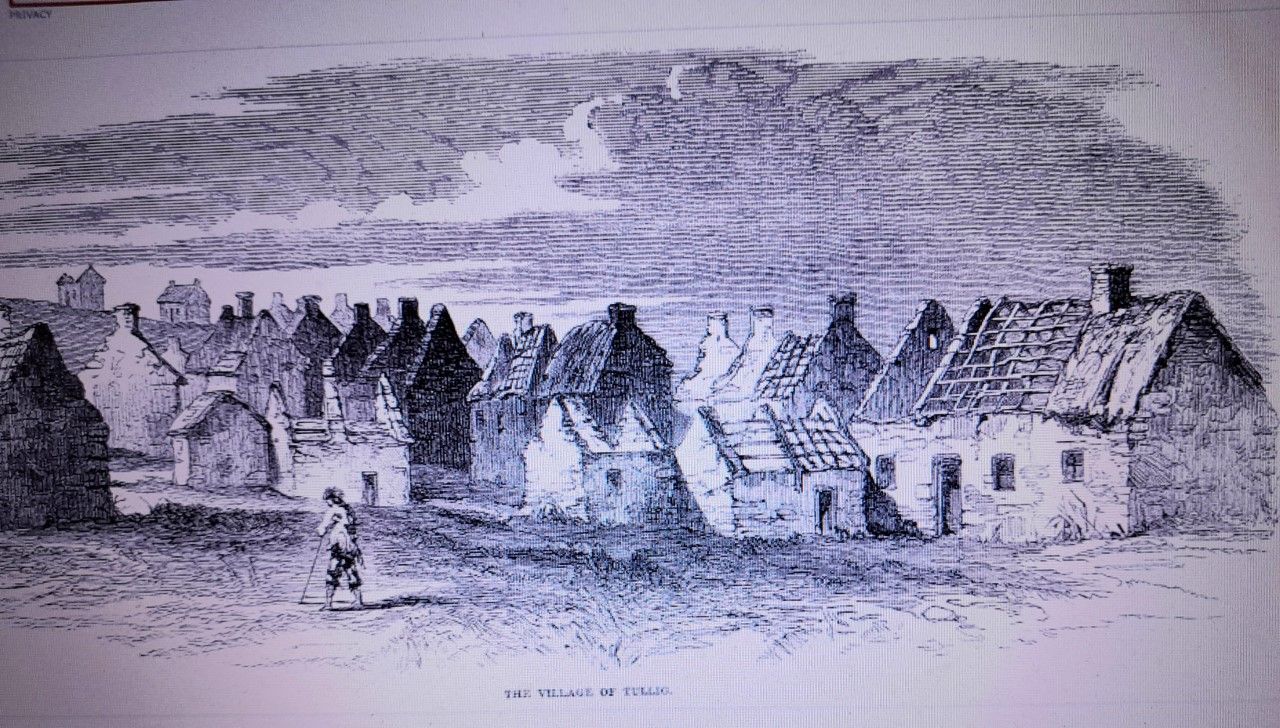

Abandoned Famine village of Tullig, Kilrush, Co Clare, Illustrated London News

A Vindicator column on June 30, 1849 – ‘More Horrors, Death by Famine’ – was filled with reports of the ravages of death, destitution and starvation across Ireland. Reports of cannibalism were reported, with one instance even being raised in parliament. The Vindicator reported on Prime Minister’s questions in the House of Commons, held on May 25, 1849. Regarding destitution in Ireland, Mr. H. Herbert asked Lord John Russell if he had received any information that a dead body had been found along the coast of County Mayo and that the starving people of the neighbourhood had allegedly eaten a portion of it. Lord John Russell said he was unaware of the “horrible occurrence referred to, but would state that an inquiry into the facts should immediately take place.”

A letter about the horrific scenes in Skibbereen, County Cork, written by Mr. N.J. Cummins, J.P, was carried in the Belfast Protestant Journal on December 26, 1846.

“Being aware that I should have to witness scenes of frightful hunger, I provided myself with as much bread as five men could carry, and on reaching the spot I was surprised to find the wretched hamlet apparently deserted. I entered some of the hovels to ascertain the cause, and the scenes that presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner in some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horse cloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached in horror, and found by a low moaning that they were alive – they were in fever, four children, a woman, and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail; suffice it is to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 of such phantoms, such frightful spectres, as no words can describe. By far the greater number were delirious, either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still in my ears, and their horrible images fixed upon my brain...

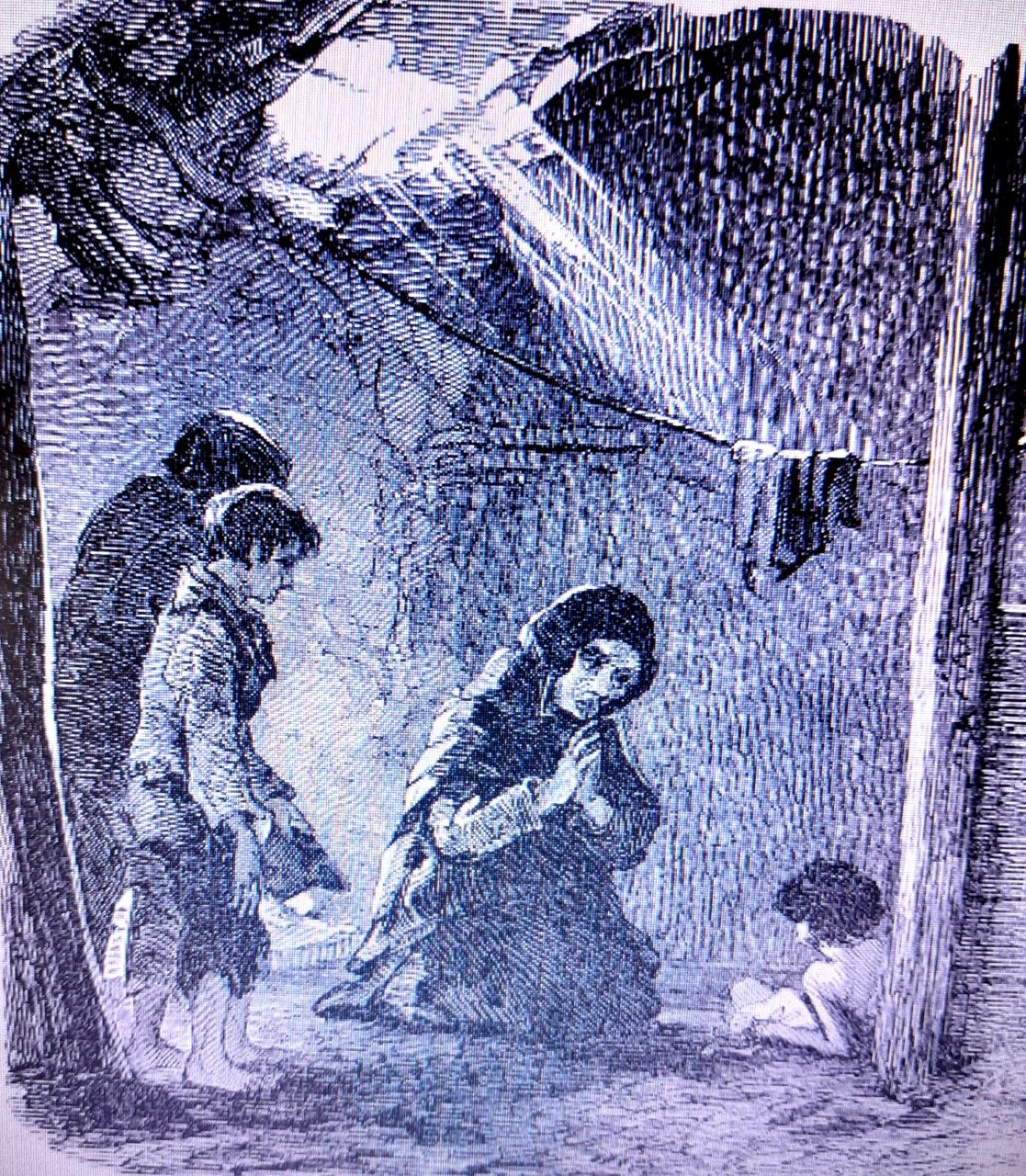

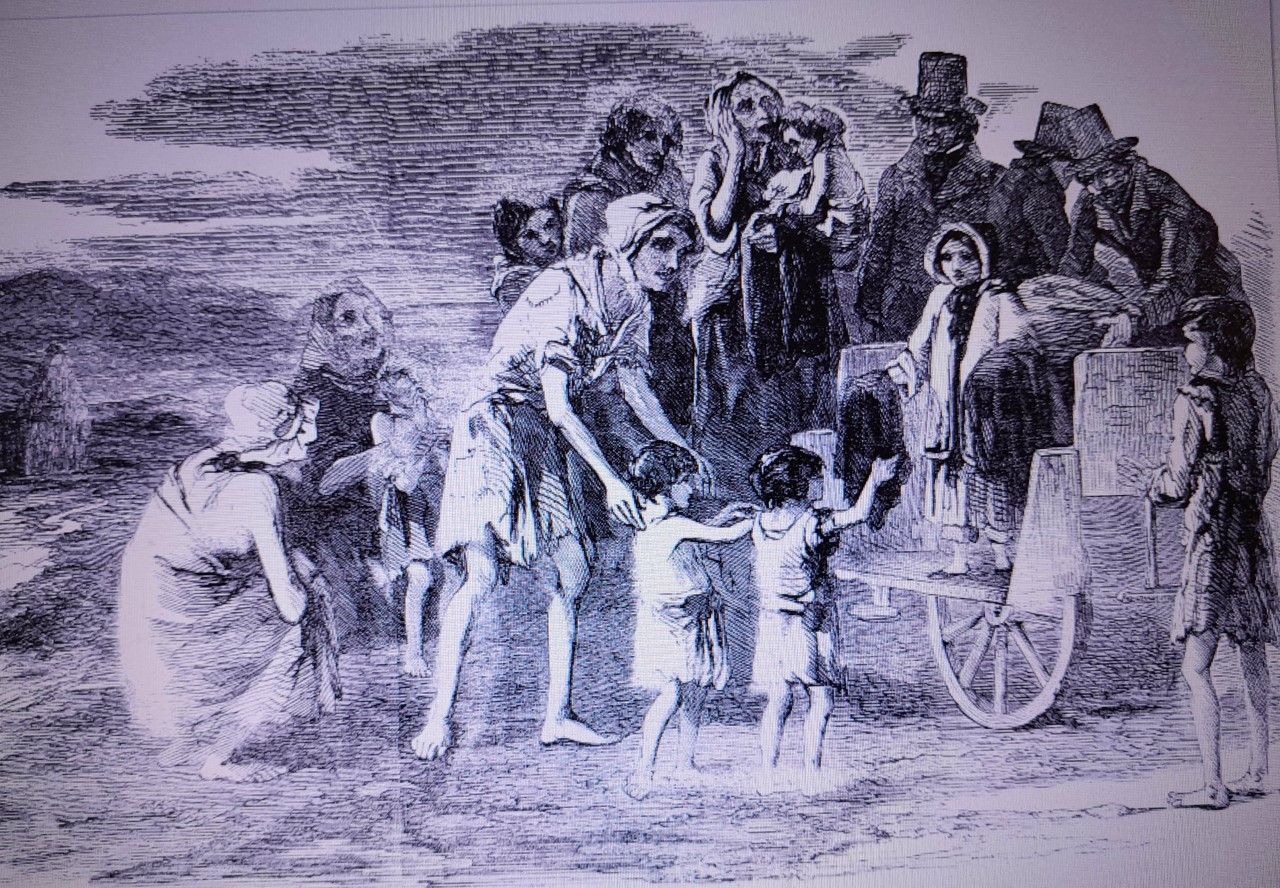

Destitute Family receiving old clothes donations, West Ireland, 1847, Illustrated London News

“I found myself grasped by a woman with an infant just born in her arms, and the remains of a filthy sack across her loins – the sole covering of herself and babe. The same morning the police opened a house on the adjoining lands, which was observed shut for many days, and two frozen corpses were found, lying upon the mud floor, half devoured by the rats. A mother, herself in fever, was seen the same day to drag out the corpse of her child, a girl aged about 12, perfectly naked, and leave it half covered with stones. In another house, within 500 yards of the cavalry station at Skibbereen, the Dispensary Doctor found seven wretches lying unable to move under the same cloak. One had been dead many hours, but the others were unable to move either themselves or the corpse.”

Against this unimaginable horror, the London Times and other prominent English media presented the Irish Famine as brought about by Ireland’s own failings, interpreted purely as an enormous ‘financial burden on the British Imperial Exchequer’; an ‘inconvenience’ for the damage it was doing to England’s prosperity. In March 1847, the London Sun, representative of the leading English press, expressed the opinion that sympathy for Ireland was fastly waning: “A grievous impression appears to be present that Government can and ought to do EVERYTHING for the starving multitudes of Ireland. The notion is altogether absurd. Government has neither the power nor the moral obligation to give shelter and sustenance to the famishing millions.

“Were it to undertake anything so extravagantly beyond its capacities, the whole empire would become insolvent. Were it to take upon itself the task of feeding and clothing and employing one half of the population of Ireland, the load would be immeasurably beyond its strength – its back would be broken.”

Meanwhile, on March 13, 1847, the Dublin Evening Packet quoted with the utmost concern comments from the lead article of the London Times, revealing its prejudice, its callous disregard for the horrors of that ‘Great Calamity’ and its belief that Ireland’s people were a burden to government and the exchequer. “…the question now before the legislature, and before very long to come before the constituency, is, whether the industrious classes of England are, forthwith and for a long, long period, to sink into a nation of overworked, underpaid drudges, slaves, helps, mere mechanic operative animals, for the sole purpose of maintaining the landlords of Ireland in disgraceful luxury, and its peasants in disgraceful barbarity and sloth.”

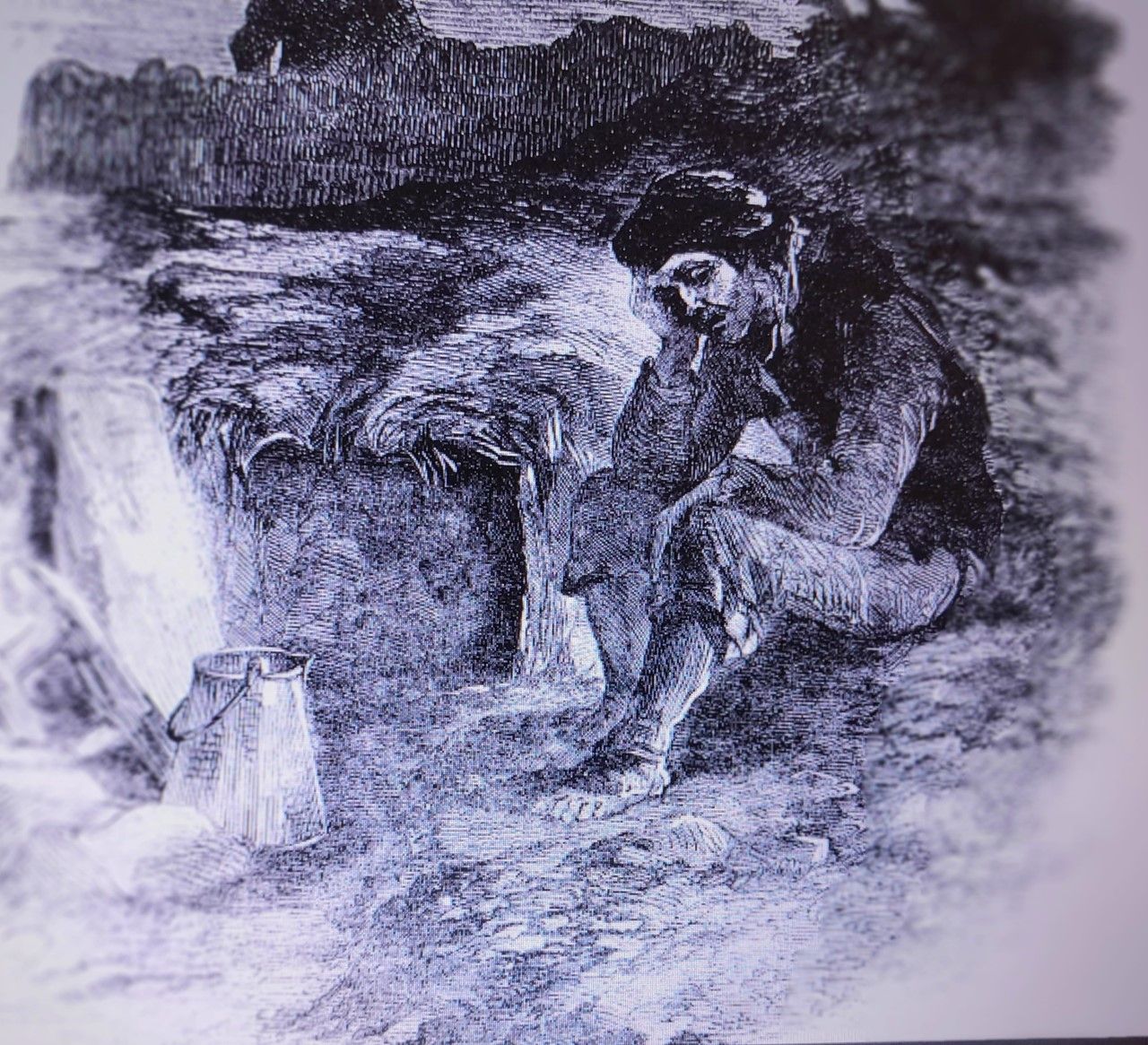

Famine victim alone , West Ireland, 1847, Illustrated London News

The Times Newspaper was a malign influence on Irish affairs, consistently judgemental, disparaging and racist towards the native Celtic Irish from the onset of the Famine.

The appalling extent of suffering and deaths was absorbed into that racist mindset and simply remained at the level of the ‘subconscious’ within its journalism. Their political influence with government was such that the previously-quoted assertion was sound: the Times was the “Attorney-General of Irish starvation”.

The depth of the psychological trauma to the soul of the Irish people within Ireland and across the world after the Great Famine was incalculable. The wounds burned deeply into the heart and soul of the people, transmitted across generations in folklore, oral tradition and history. The words of Cecil Woodham Smith in ‘The Great Hunger’ (1962) still resonate: “The Famine left hatred behind. Between Ireland and England, the memory of what was done and endured has lain like a sword. Other famines followed as others had gone before, but it is the terrible years of the Great Hunger which are remembered, and only just beginning to be forgiven.”