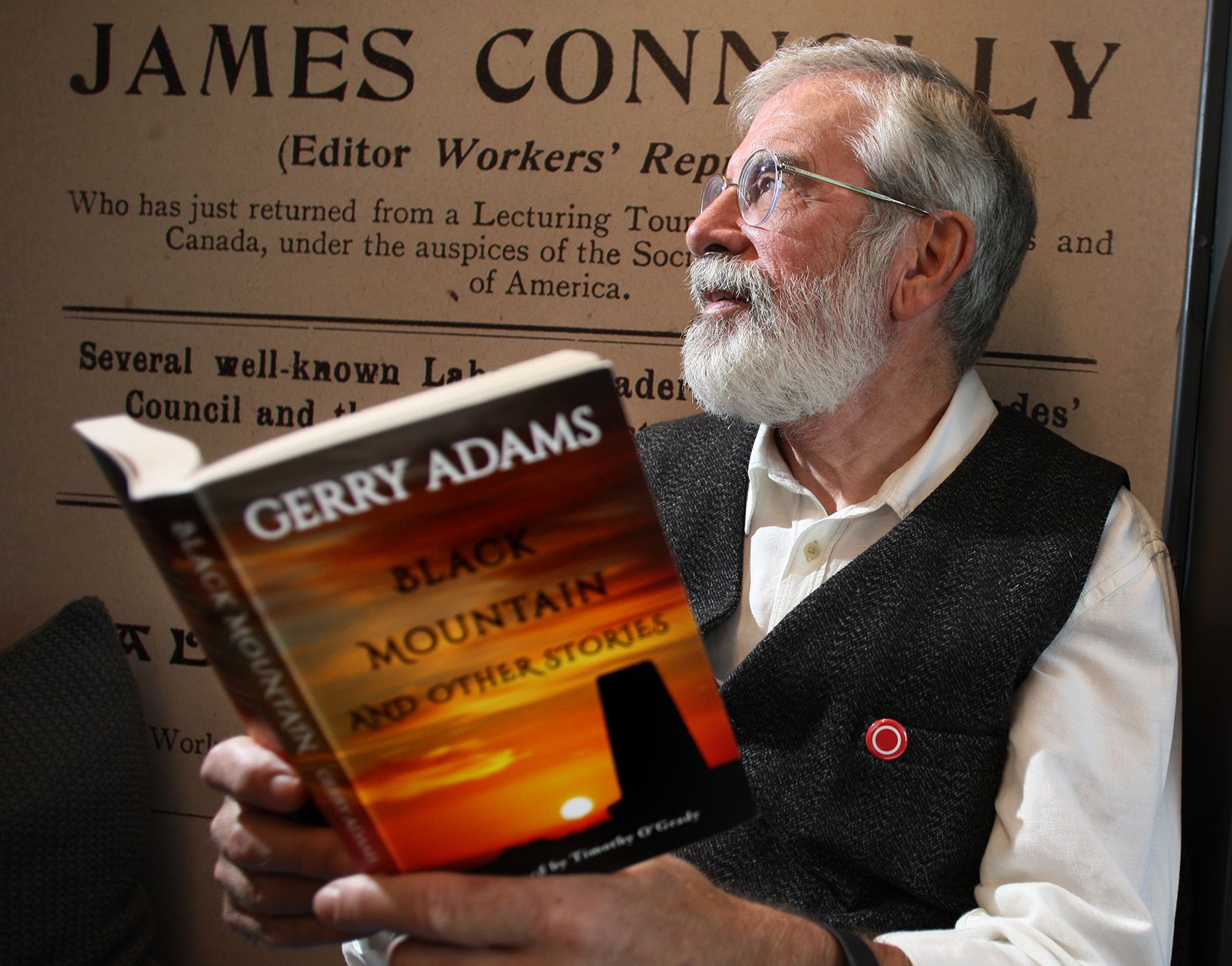

Gerry Adams, BLACK MOUNTAIN AND OTHER STORIES. Brandon Press, Dublin, 2021

In his introduction to Black Mountain and Other Stories, Timothy O’Grady suggests that Gerry Adams enjoys writing because it is therapeutic – to write means he’s able to snatch solitary periods of time from a busy public life. This may be true, but this collection of stories is more than therapy.

The title hints at the territory covered. The stories are overwhelmingly local, which must add a layer of pleasure for readers familiar with the streets and sights of West Belfast and its hinterland. But as William Blake found the world in a grain of sand, these stories push deep into the local and find the universal.

The relationship between the Catholic Church and the people it serves, for example. In the ironically titled ‘A Good Confession’, we witness a clash between a pious older woman and a keen young curate. Mrs McCarthy notes that the new curate is “not bad-looking in an ascetic sort of a way” before blurting out an after-Mass criticism of his anti-republican sermon. As soon as she’s said it she wishes she hadn’t. And she doubly wishes she hadn’t after when her son fumes at the priest’s nerve: ‘The ignorant good-for-nothing wee skitter.’ The way the story eases towards a broader view of morality is tender and convincing.

Religion is again a theme in ‘Heaven’, where a little girl tries to grapple with the sudden disappearance of older people she’s close to. Where is this heaven they go to? Why can’t she go there? When is the person coming back? One of the problems adults have is that they forget what it’s like to be young. The unsentimental picture of young Niamh shows that the author hasn’t.

While all the stories spring from the same local territory, there is variety within its boundaries. In ‘The Sniper’, the reader shares the physical and occasional moral discomfort of the sniper, as he waits for his target and life continues around him, with Mrs O’Brian calling for a chinwag over the garden fence with her neighbour Maggie. The tension builds, the sniper fires but we don’t know the outcome until the last sentence (Spoiler Alert): “The British officer’s expression, staring unseeing at the clear Irish sky, was curious, surprised.”

A gentle element of humour is found in most stories, but in ‘Up for the Match’, it’s allowed to gallop free. ‘The Cube and Wee Root were great mates’ it starts, as we listen to the barman being lectured on the need to wait for the pints order and presume nothing. The plot and the friendship thickens as Wee Roots invents a dead uncle in Glasgow in order to finance his trip with The Cube to the All-Ireland Hurling Final in Croke Park. The glorious fry breakfast served on the train, the need to pace their pints over the course of a long, exciting day – it’s impossible to read without laughing out loud. Gerry Adams knows the hurling community.

‘The Wrong Foot’ tells how Long Kesh prisoner Paddy forms a friendship with Trevor, who of course kicks with the wrong foot. The way their friendship develops, their conversation spattered with slagging (‘And by the way’ Paddy reminds Trevor ‘this is the mainland’; Trevor passes a Polo peppermint to Paddy: ‘Your breath still stinks.’) Even Martin McGuinness is given a brief walk-on part in the story. But the laughter shades into something more sober as the two men’s friendship comes to a sudden and sickening end.

‘The style is the man himself’ Buffon declared, and the Gerry Adams who emerges from the style of these stories is sympathetic, honest and (maybe above all) great fun. Reality is never dodged, but small moments of laughter and beauty thread each tale.

I don’t know how many shopping days there are until Christmas, but you could do worse than get this book on your list.