MID-19th century Belfast was notorious for the dreadful state of public health among the poverty-stricken working classes. The hideous “dark and noisome haunts” of courts, tenements and alleys, such as in the Smithfield, Cromac, Docks and Millfield districts, were notoriously squalid.

Thousands of its poor were packed into overcrowded slum housing, without even backyards, deprived of sufficient supplies of clean water, natural light, and fresh air, adjacent to open sewage channels in the streets – “...the miserable abodes of darkness and sorrow.”

Government inquiries into the causes of poverty and deteriorating public health accepted the urgent necessity for sanitary reform legislation as the catalyst for change.

One response to address public health and the related issues of cleanliness and personal hygiene was the movement in England for the provision of ‘public baths and wash-houses’, begun in the early 1840s.

It originated in Liverpool, initially inspired by the voluntary efforts of a young Irish immigrant, Kitty Wilkinson, whose poverty-stricken family emigrated from Derry to England in 1794.

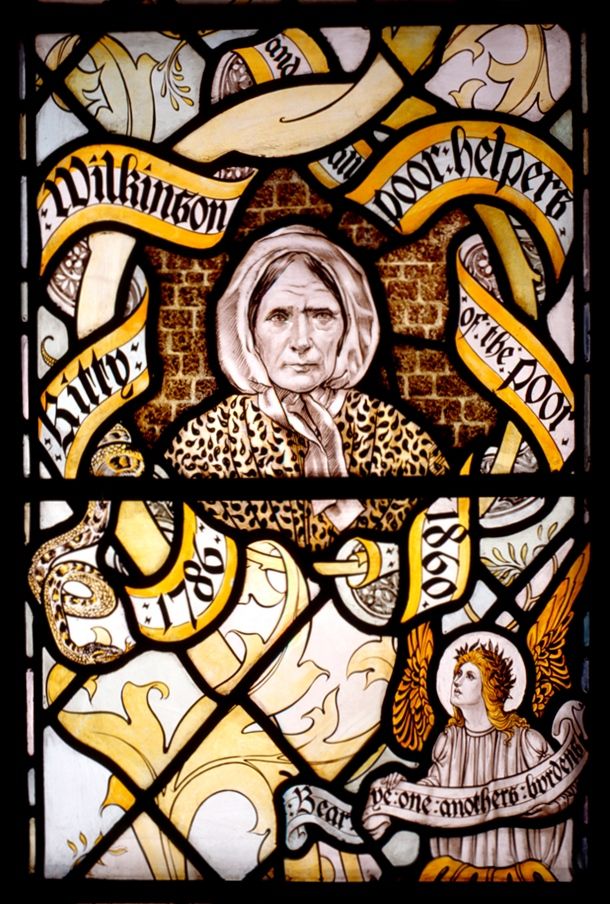

Kitty’s inspirational voluntary work among the poor in Liverpool led her to become known as the ‘Saint of the Slums’. In 1832, during a cholera epidemic she offered the use of her house, its boiler and yard to neighbours to wash their clothes, and showed them how to use a chloride of lime (bleach) to get them clean. In doing so she potentially saved hundreds of lives by improving their hygiene and cleanliness. Through her inspiration, the Corporation of Liverpool opened the first ‘warm water public baths & washhouse’ in Frederick Street, Liverpool, in May 1842, the first of its kind in the UK, with Kitty appointed as its first superintendent.

Famous stained glass window of 'Noble Women' portraying Kitty Wilkinson in the Lady Chapel in Liverpool Cathedral, (Creative Commons Licence)

Thereafter, her life and work were influential in government policy to promote the spread of public baths and washhouses by local authorities in Britain and Ireland. In 1846 it passed the ‘Public Baths and Wash Houses Act’, empowering local authorities to fund their construction through repayable government loans or by levying an additional local rate.

A town meeting was held in Belfast on February 12, 1845, comprised mainly of ‘influential’ people – industrialists, doctors, clergy and so on, at which the ‘Society for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Working Classes’ was formed on the initiative of prominent industrialist and Lord Mayor, Andrew Mulholland, later supported by the pioneer of sanitary reform in the town, Dr AG Malcolm, as advisor and director of its activities. At the meeting its first major action plan was approved – to establish, by public subscriptions, the Belfast Public Baths and Wash Houses. Their aims were ambitiously stated: “…to tend most effectually to stay the progress of disease, by prevention, which is better than cure – thoroughly improve the moral tendencies and character of the working classes – invigorate and renew the mental faculties – render them more susceptible of advancement, and thus, generally, ameliorate their condition.”

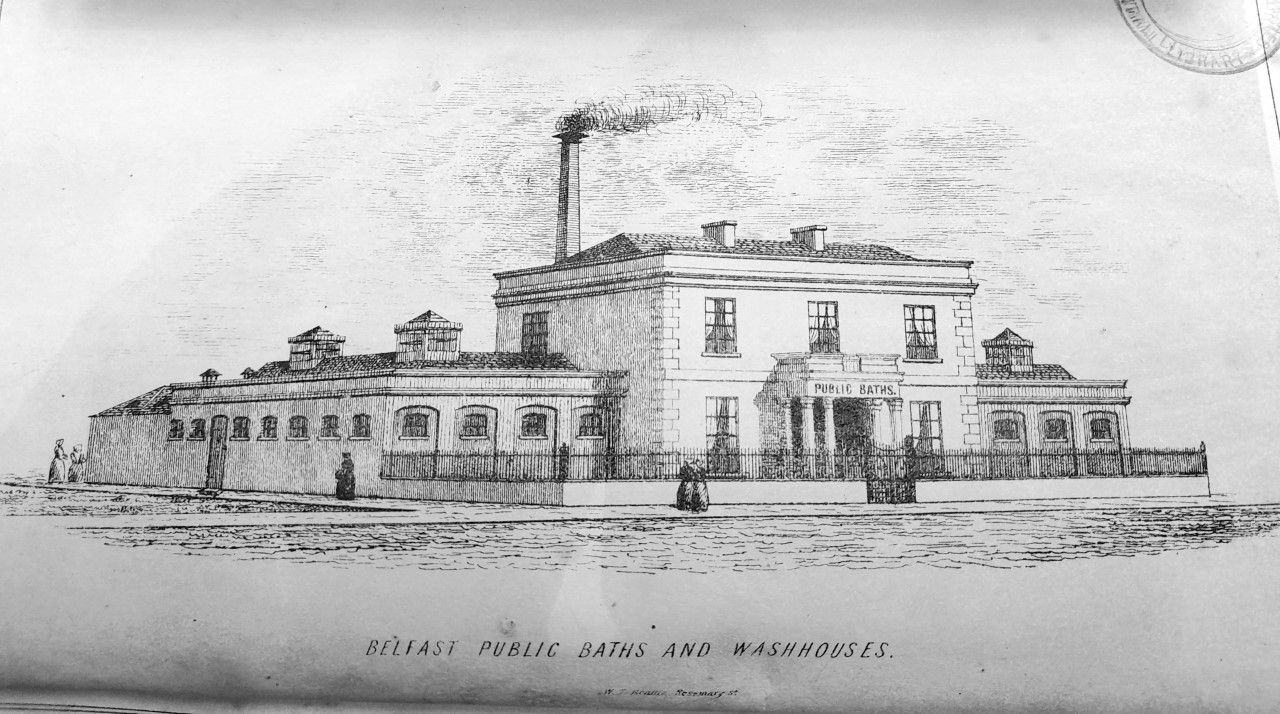

Designed by Belfast architect Charles Lanyon, the building was located at Townsend Street on the Falls Road, and officially opened on May 3, 1847. Its establishment was ground-breaking, for it was the very first of its kind in Ireland, subsequently influencing baths and wash-house projects elsewhere in Ireland, beginning with Dublin in 1851.

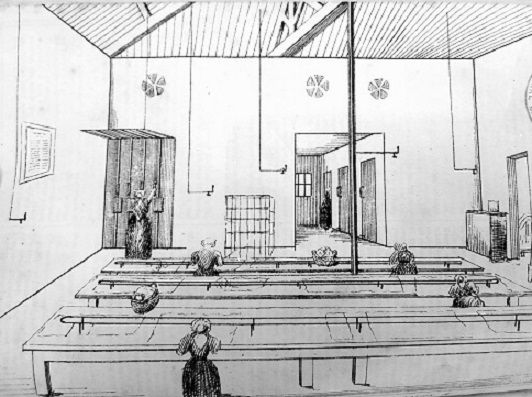

In April 1847 an article written by Dr Malcolm appeared in the Belfast People’s Magazine titled ‘Belfast Public Baths and Wash Houses, the Advantages of the Institution’, including details of its facilities and illustrative sketches of its interior and exterior. Given the appalling living conditions of the labouring poor, he estimated that at least 8,000 families were in need of the facilities, representing tens of thousands out of Belfast’s population of almost 100,000. Their use was intended primarily but not solely for use by the working classes of the town and its facilities were accordingly affordably priced. It opened at 6am in the morning from May to November and at 7am for the rest of the year, closing at 10pm at night, and on Saturdays at 11pm. Supervisors were present at all times if needed.

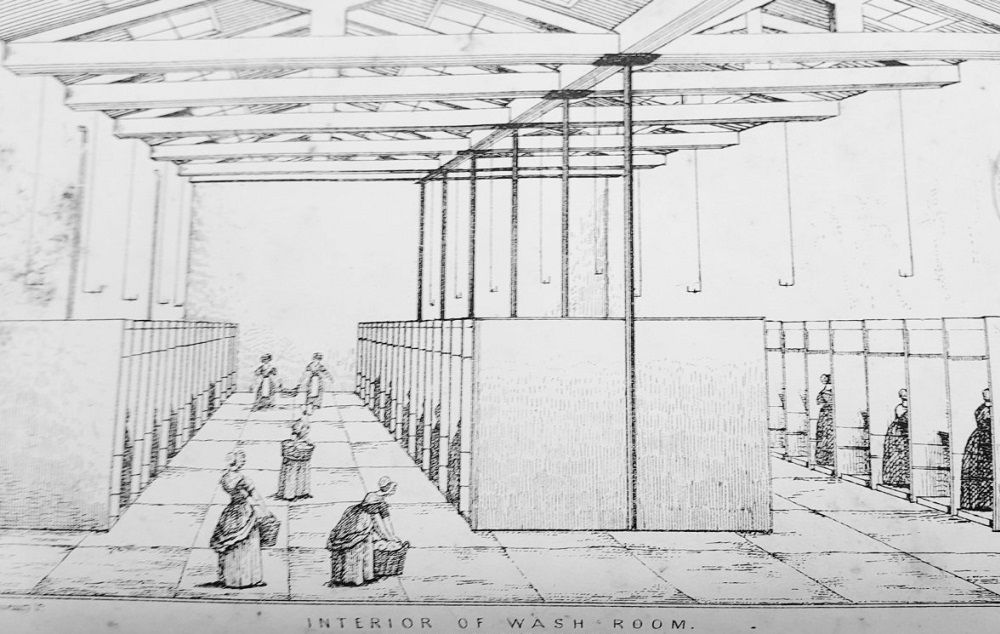

The spacious wash-houses enabled women of the city to do three days work in three hours (Belfast Central Library)

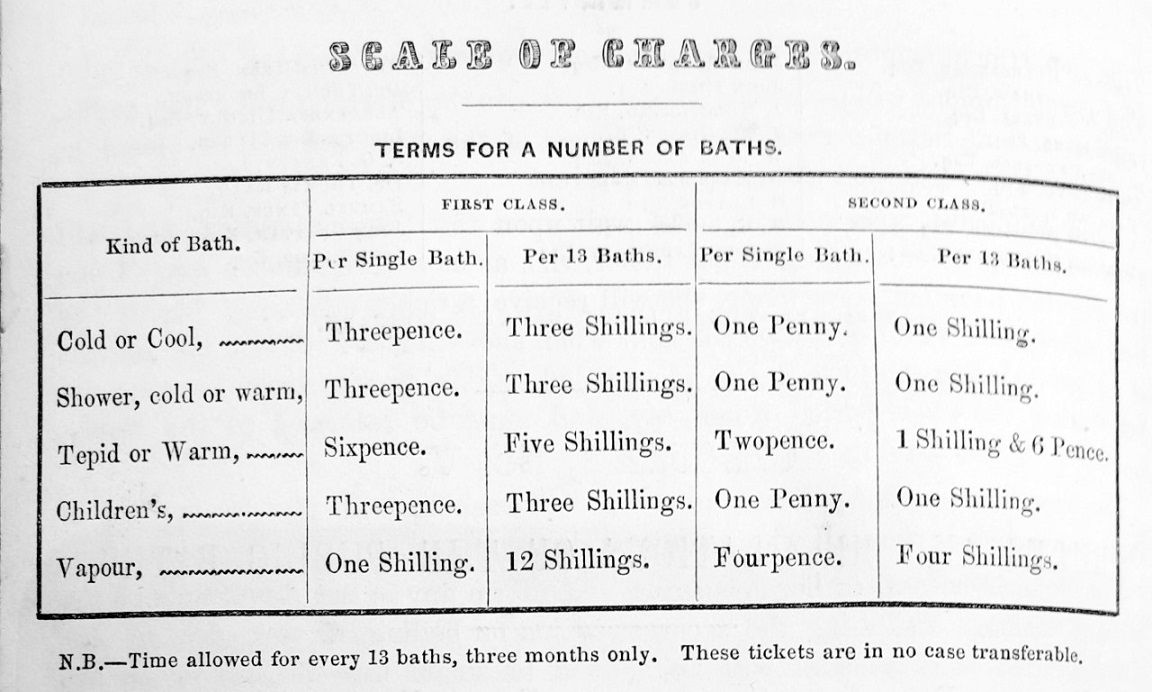

The baths department had 13 baths and could accommodate 400 persons daily. Bath facilities were divided into first and second class. A single first-class cold bath was 3d, warm 6d; second class cold bath was 1d and second class warm bath 2d. The wash houses had 68 washing stalls costing 1d for three hours' use, allowing family things to be washed, cleansed and ironed in a much greater time than normal laborious processes at home. Soap and soda were provided at cost price. About 400 people could use the washing facilities daily “and if a woman makes good use of her time... she may go through more work by the help of these appliances in three hours than she could possibly manage in three days at home.”

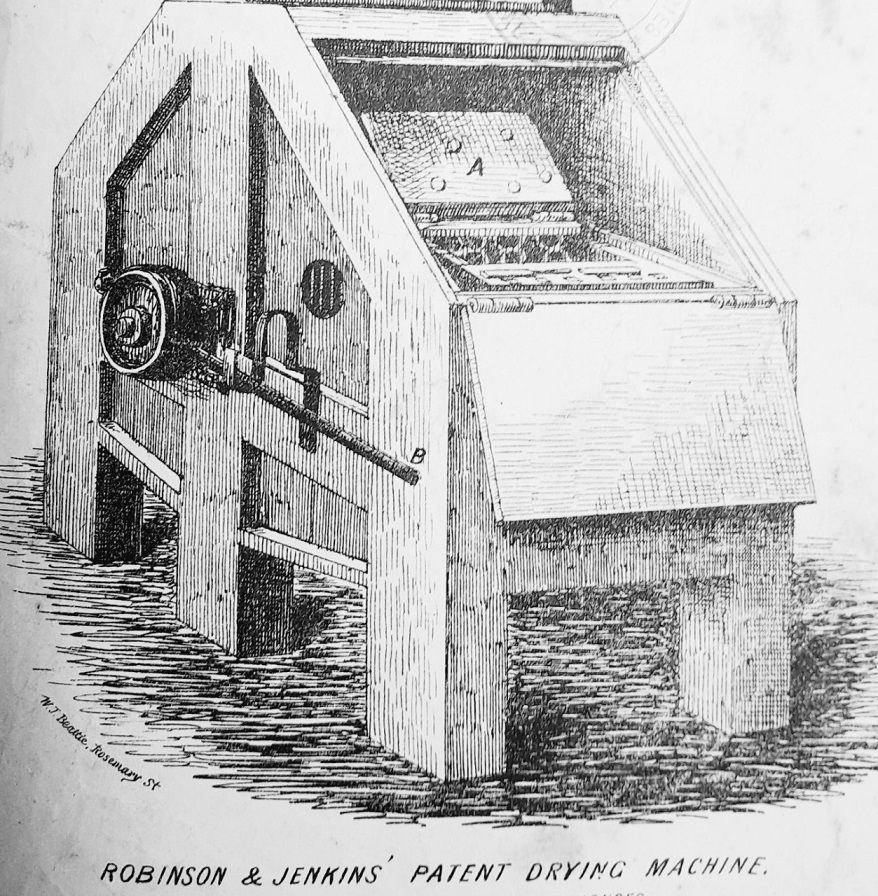

A new machine for partially drying clothes was installed – the state-of-the-art ‘Robinson & Jenkins Drying Machine’, replacing the common task of wringing by hands, allowing even the heaviest articles to be wrung in a few minutes without damaging the texture of the material in any way. Clothes could then be placed on drying rails and a few minutes of the hot blast drying apparatus completed the process and they were ready for the heated ironing tables where irons were provided.

The baths and wash-houses were initially welcomed by all sections of society and enthusiastically received by the Belfast press as hugely important for social progress and their obvious benefits for public health, although the issue of its financial sustainability would soon surface as contentious and problematic.

Its enthusiastic reception was also matched by the numbers using its facilities. In the first nine days to June 2, 328 people took baths and 6,158 articles of clothing had been washed.

The various views expressed summed up the hopes and expectations from its sponsors and supporters: improved health and well-being, protection from disease, self-respect and moral elevation among the working classes, all tending to a more stable harmonious society in Belfast. The News Letter on April 30, 1847, commented: “We trust this institution will be extensively resorted to by the class for whom it is intended, as cleanliness of person and apparel will do much to prevent the increase of those contagious diseases which are so prevalent in town.” On May 7, the same newspaper predicted the ultimate prize in the waiting: “...we don’t affirm too much in saying that the erection of the public baths and wash houses will affect a social revolution of the happiest kind in the ‘Athens of Ireland.’”

Robinson's and Jenkin's Drying Machine (Belfast Central Library)

From a different perspective, the Banner of Ulster, May 7, 1847, wrote approvingly of the progressive and enlightened views of sanitary reform and the baths and wash-houses successfully eclipsing an underlying wariness and resentment felt by elements of the dominant and influential class towards the elevation of the labouring poor: “Much abuse is sometimes showered upon the working classes by one section of the body politic, who frown upon them as beings ever... discontented with their condition... if they find them taking the initiative in any movement calculated to elevate them in the scale of social existence... fearful of too sudden a transition from filth to cleanliness, from disease to health and from a miserable existence to one of comparative comfort and respectability, [the dominant are] quite contented to allow things to remain as they are.”

Later, it was this section of the town’s social and civic elite, whose interests were represented on the Town Council, who would ultimately decide the fate of the baths and wash houses.

The total activity at the Baths and Wash-Houses for the eight months ending January 20, 1848, was reported as follows. The baths department had attracted a total of 17,258 bathers and the washing department had a total of approximately 207,000 articles of clothing washed, dried and ironed.

Despite this high level of activity, the facility’s potential and future became seriously compromised, as at that point it was not sufficiently self-supporting financially, although substantially more income could have been generated by the larger facilities initially designed and planned but ditched as unaffordable. Ultimately its health and sanitary benefits for the town were undermined by the failure to realise the anticipated transfer of ownership from the Society for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Working Classes to the Town Council. The Society never intended to manage the facilities permanently; its capacity directed mainly at a range of other activities for the working classes.

In 1848 the Town Council rejected the use of the powers of the 1846 Act to buy out the baths and wash-houses from the Society and a long-running dispute commenced from the late 1840s to have the decision overturned. Andrew Mulholland explained at the meeting held of the Town Council on January 1, 1848, that their Society strongly anticipated that when the advantages and success of the institution would be practically realised, there would be no difficulty in securing the local application of the Baths and Wash-Houses Act by the Council, stating emphatically: “Originated as the design was by a large and influential town meeting, they were not prepared for the opposition which has been latterly organised with a bitterness and perseverance for which I am at a loss to account.”

Scale of Charges Belfast Baths and Wash-houses, 1847

The majority of the Town Council were concerned about municipal finance issues, with additional levies seen as a burden on the ratepayers, combined with doubts about whether the baths and wash-houses could generate sufficient income to make it a viable self-financing business. Other concerns raised were whether the paupers were able to afford access to them. Others suggested it was more viable for the Council to construct their own baths and wash-houses at convenient sites in town accessible to the poor for cheaper building and running costs. These were formulated in a set of amendments for further investigation, voted in favour of by 15 to eight; the matter was deferred for consideration at a later date. In February 1849, the Baths and Wash-Houses Committee in desperation launched a public appeal supported by local newspapers to rescue the premises from closure, as it had an outstanding debt of £2,700 to pay towards initial total expenses of £3,900 incurred in the construction and overhead costs of the facility.

These financial difficulties, according to the Banner of Ulster, were in large part created early on, when after contributions from the general public were pouring in enthusiastically (£1,240), the momentum stopped when news emerged that the Town Council were applying for powers under the new 1846 Act to finance the baths and wash-houses. However, when the Council withdrew their application, it was almost impossible to re-energise the initial momentum of public donations.

In 1851, the Society organised a petition, signed by over 1,300 people including 88 doctors, to ask the Corporation to buy the baths from them. By 1853 there was considerable public concern at the threat of closure. An increased entrance fee was charged in an attempt to reduce the debts. The case went to Chancery, and the Corporation eventually agreed to buy the enterprise for a price of £950, once it had established a special rate for the purpose, but it later reneged on the promise. In January 1860 the Society put the baths up for sale, hoping to find a commercial buyer, with no success, and eventually sold the building in 1861 for just £200.

The Ironing Room (Belfast Central Library)

The plan of the Society for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Working Classes, was intended as a ‘first phase’ driven by ‘voluntary’ efforts and based on an ‘assumption’ that the Town Council would take transfer of ownership and financial control after the necessary legislation was passed (the ‘Public Baths and Wash-Houses Act’ 1846).

Such expectations were arguably premature without first securing a firm commitment from the Town Council for such an undertaking. Secondly, it indicated a certain lack of insight into the forces at play among certain sections of the town’s civic elite. Within the Town Council there existed a certain friction between advocates with progressive views of social and sanitary reform, desirous of maintaining a healthy social fabric among the town’s population, and those with conservative views, who measured social justice and progress against financial outlays and profit margins. The Banner of Ulster clearly understood this reality, commenting at the time: “Merchants and manufacturers, however opulent and charitable, will not contribute hundreds of pounds until they are fully satisfied that the project... is feasible and calculated to prove advantageous. Hence it is that the numerous schemes of zealous but imprudent social reformers have been but slightly considered and that the various sources of disease almost peculiar to the labouring portion of society resident in large towns have been almost totally neglected.”

It was not until September 25, 1879, that the next Baths and Wash-Houses, erected by Belfast Corporation, was formally opened at its new location at Peter’s Hill and Old Lodge Road. The town’s Mayor, Samuel Browne, in a long congratulatory speech acknowledged many people’s assistance over many years for the achievement and talked up the potential benefits for the health and well-being of the working classes. It was not insignificant that he made no reference to the Society for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Working Classes or the original Baths and Wash-Houses established at Townsend Street.

Given this, it’s important to remember how the story began, for in 2012 a statue of Kitty Wilkinson was unveiled in the Great Hall of St George's Hall, Liverpool – the first woman to be so honoured. Kitty is featured in one of the Cathedral’s famous ‘Noble Women’ stained glass windows in the Lady Chapel in Liverpool Cathedral, where she’s commemorated as ‘Helper of the Poor’.

It was later written: “She was the widow's friend. The support of the orphan. The fearless and unwearied nurse of the sick. The originator of Baths and Wash-Houses for the poor. ‘For all they did cast in of their abundance; but she of her want did cast in all that she had, even all her living.’ (St. Mark, 12:44).”