THE mid-nineteenth century witnessed the development and acceleration of the sanitary reform movement in Belfast. This was led by dynamic pioneering individuals within the medical provision such as Dr A.G. Malcolm with his ground breaking research and reports in 1848 and 1852 for the Belfast Social Inquiry Society on the ‘Sanitary State of Belfast.’

It was also advanced through many charitable and self-help groups active in communities and advocating the case for public health and sanitary reform, including the Belfast Working Classes Association (1846), in which Dr Malcolm was also central as its President and Secretary. Its objects were the “general improvement of the condition and character of the working community of Belfast and to increase the knowledge and elevate the condition of the working classes”.

Dr Malcolm’s reports provided alarming revelations on the sanitary and public health circumstances of Belfast. Between 1817 and 1847, 62,000 people had suffered from the epidemics of typhus fever, of whom 6,000 had died. Next to Dublin no other town in Ireland or any comparable town in Britain had been so severely affected. The most shocking disclosure was that the average age at death in Belfast by the mid-1840s was just nine-years-of-age.

The Working Classes Association launched the monthly ‘Belfast People’s Magazine’ in January 1847, writing regularly thereafter about the importance of public health and sanitary reform. Early that year they began by completing a detailed inquiry into the health and sanitary state of the New Lodge district, a ‘suburb’ of Belfast.

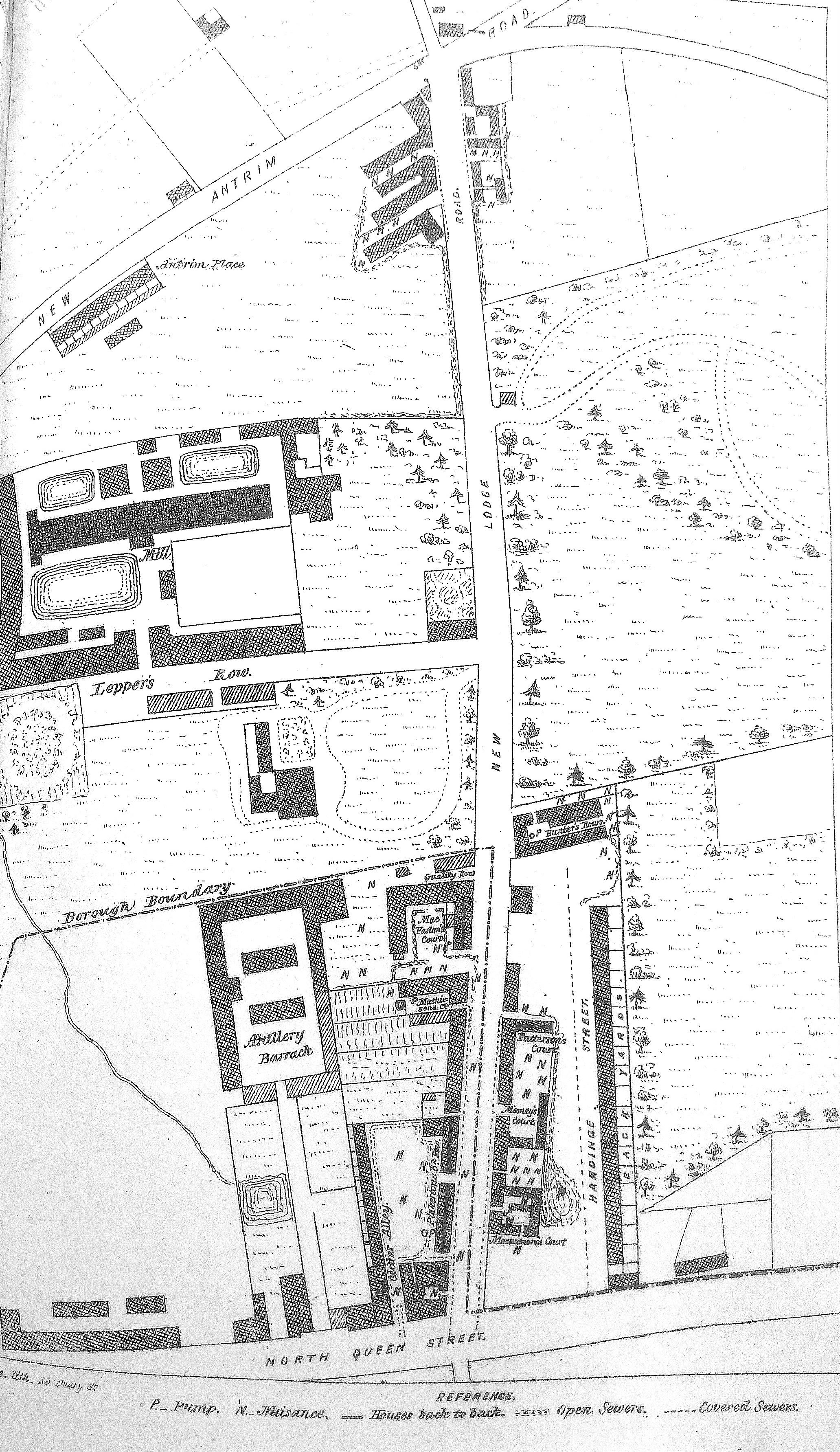

It stated, “the locality…occupies a space of about 280 furlongs, situated at the N.W. boundary of the town upon a gentle slope, with a S.E. aspect. The main street – in part of a road – runs through its entire length, rising from North Queen Street to the New Antrim Road, in a westerly direction. The locality may be characterised by a number of detached clusters of houses on each side of this main line, and surrounded at considerable intervals by open spaces and public buildings.”

The inhabitants worked mainly as general labourers, tradesmen, ‘dealers’ and mill workers. There were 312 dwellings based around three main streets with 157 houses, seven lanes and alleys with 48 houses, eight courts with 101 houses and four entries with a total of six houses. Some of the place names are familiar to this day, and others long gone: New Lodge Road, North Queen Street, Lepper’s Row, Harding Street, Gutter Alley, McFarlan’s Court, Pinkerton Place, Turnpike Street, Thompson’s Row, McNamara’s Court, Patterson’s Row, Hunter’s Row and others.

FIELDS AND HOMES: Map of the New Lodge district, 1847, Belfast Peoples' Magazine, Francis Joseph Bigger Collection, Courtesy of Belfast Central Library

Above Artillery Barracks was a school and north of Lepper’s Row was the Cotton Factory built in the early 1800s and for a period the largest cotton textile mill in Belfast, McCrum, Lepper & Co, employing in 1820 about 300 operatives, many locally. It was a massive structure at 200 feet long and five storeys high. The district was surrounded on its eastern side by fields and tree lines. Their New Lodge investigations supported the findings of the medical profession on the causes of sanitary and health problems to be found generally in the poorest districts of Belfast, and they provided as typical of the locations of habitation there, the following two descriptions:

“Gutter Alley, with nine houses situated at the lower end of Pinkerton’s Court, though accommodated with two small sewers, terminating in the North Queen Street main, seems to be a regular rendezvous for all the filth that can find its way from the large sloping area adjoining, and is always, more or less, covered with accumulations.”

“Pinkerton’s Place, enclosed by 41 houses; and yet, we venture to affirm, nowhere can there be found a greater accumulation, over its whole surface, of filth and corruption. Its surface is most irregular, and manure heaps are seen in every direction, with tiny streams issuing from all parts…No one thinks of their removal, and the poor residents must suffer a constant nuisance before their very doors. There is one covered sewer at its lower end, which, however, is wholly inefficient…”

The manure problem was a notorious sanitary evil affecting Belfast in the mid-19th century. In November 1846 ‘The Banner of Ulster’ sent its reporter around the streets, and lanes of the town to assess the Town Council’s work in cleansing and public sanitation. The subject of investigation was ‘dung heaps’, and the emerging picture was far from flattering. The reporter counted 1,392 dung hills left on the streets which were to be disposed of. The newspaper later stated that this was likely an underestimate of the true figure if a more extensive inspection could have been achieved and that it was more realistic to estimate the “public thoroughfares contained ‘six thousand’ dung heaps – a heap of filth for every three families.”

The inquiry of the Belfast people’s Magazine concluded that in the New Lodge district, where there were substantial differences in the dwellings as constructed and laid out, there were to be found significantly different health outcomes for the inhabitants. Comparisons with the examples of Leppers Court and Hunter’s Row in 1847 supported this conclusion.

Dr R.F. Dill, Medical Attendant for the Hospital District of which the New Lodge, formed a large part, when asked by the magazine for his assessment of the health and sanitary conditions of the New Lodge, wrote: “With a few exceptions, the houses are constructed in a wretched manner; a large number of them consist of double rows clapt together…the occupiers having no yard to their dwellings, having no proper sewers, or drains, running from them, are obliged to throw slops, refuse, &c,, before the door…The whole surface of this neighbourhood is constantly kept in a filthy, and most abominable state, covered thickly over with heaps of manure and every kind of nuisance, which when rain falls penetrates the earth, finding its way into (and poisoning and polluting) the very springs and foundations from which the inhabitants are obliged to draw water for drinking…The crowded state of these habitations increases the evil tenfold. The poverty and its usual accompaniment, filth, in which so many of them are steeped, tend still further to aggravate their wretched condition.”

Belfast had been particularly hard hit during the Famine by outbreaks of epidemic disease of typhus fever in 1847 and cholera in 1849; “two epidemics of unexampled severity.” The General Dispensary Report for May 1847 stated of the Hospital District, covering the New Lodge and adjoining areas, “Fever, dysentery, small pox and measles were prevalent. A very considerable number of fever patients cannot be admitted to hospital, owing to the want of sufficient accommodation.” It revealed that in 1847 there were 1,103 fever cases, with 616 of these supplied by just ‘twelve’ streets including, New Lodge Road, Pinkerton’s Row, McNamara’s Court and Hunter’s Row. The Dispensary Report for the entire Hospital district in 1849, when the cholera epidemic struck Belfast, showed that 3,108 patients were treated.

Earlier in February 1847, Dr E. Lamont, Medical Attendant of the ‘Hospital District’ including the New Lodge area, revealed the horrors of the impact of famine and disease on the families there, stating, “…poverty, in its most horrifying form, is seen in the most wretched dwellings of the poor alone. It is there, when all means of sustenance are gone, and cold and hunger and disease, are striving for the mastery, that you see misery indeed.”

“How often have I been sent for, during the last two or three months, to visit such cases, (and they are still rapidly increasing), where there was not an article of furniture left in their miserable apartment, not even a stool to sit upon, and their bed a grain of straw – laid on a damp earthen floor…

In Lepper’s Row with 209 inhabitants, there was three rooms for every four persons, 18 cases of severe illness occurred there in the previous 12 months, five were fever. Five deaths occurred in that time, all from pulmonary consumption (tuberculosis). In marked contrast Hunter’s Row had just under 200 inhabitants and the proportion of accommodation was three rooms for every nine inhabitants. There were 77 cases of severe illness in twelve months of which 61 were fever, with 22 deaths, all from fever.

“Frequently have I seen them, in these dismal abodes, without a spark of fire; and when such a luxury is there, it rather excites a feeling of chill in the visitor, by reminding him of what it really ought to be – for round this fragment of a fire the cold and famishing children are huddling close, that not a single ray may spend itself in vain. I have often been obliged to write my lines for medicine… against the door or wall of the apartment, no article of furniture being in the room on which I could lean, for that purpose; and when visiting in the evening, I have sometimes found the family without a candle, and have been obliged to borrow one from a neighbour, to enable me to see the patient, and write my prescription.”

He suggested, to those who doubted how bad the state of the poor had become with the Famine and typhus fever epidemic, to visit the lanes and alleys of Carrick-hill, North Queen Street or New Lodge Road, “…and they will see sufficient…to blanch the cheek with horror, or moisten it with the tear of pity…”

The inquiry of the Belfast people’s Magazine concluded that in the New Lodge district, where there were substantial differences in the dwellings as constructed and laid out, there were to be found significantly different health outcomes for the inhabitants. Comparisons with the examples of Leppers Court and Hunter’s Row in 1847 supported this conclusion.

In Lepper’s Row with 209 inhabitants, there was three rooms for every four persons, 18 cases of severe illness occurred there in the previous 12 months, five were fever. Five deaths occurred in that time, all from pulmonary consumption (tuberculosis). In marked contrast Hunter’s Row had just under 200 inhabitants and the proportion of accommodation was three rooms for every nine inhabitants. There were 77 cases of severe illness in twelve months of which 61 were fever, with 22 deaths, all from fever.

They observed that greater proneness to sickness and epidemic disease with higher death rates was much higher in dwellings where more people lived, crowded in less and smaller rooms. Likewise, poorer health outcomes were found in dwellings without backyards; consequently, having much less ventilation and fresh air and outside space for refuge storage. With earthen floors they were more likely to be damp and filthy as opposed to tiled floors. These same courts and lanes usually had deficient supplies of clean drinking water nearby or water for washing or cleansing; were usually without proper drainage and sewage disposal and in close proximity to accumulations of fifth, foul streams, cesspools and manure heaps. Unfortunately, this was the case with Hunters Row in almost all these instances.

Lepper’s Row by contrast had the advantages of greater room space and size per inhabitant, ventilation, fresh water supplies, backyards and refuge disposal, drainage and sewage networks and flagged ground floors that were dry and allowed for regular cleansing. It was clear that poor health, and high levels of premature death could be explained by local causes, which in large measure could be addressed by effective sanitary legislation, housing and sanitary reform.

The Belfast Peoples’ Magazine concluded their inquiry, “…we must state that, taken as a whole, the New Lodge Road district is lamentably low in a sanitary point of view…We ask, is such a state of things to continue longer? Are we to allow death and disease to maintain a quiet possession of this ill-fated locality? We solemnly believe, that every person who feels as we do in this matter, and who yet withholds his support and influence in the cause of sanitary reform in our own town, must consider himself deeply culpable. Such a sanitary state as we have depicted, is a disgrace to us all.”

Brendan Muldoon©2022