SOME things happen by chance. In 1985, two men, one from Japan and the other from Donegal, were awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine for the discovery of the anti-parasite drug ivermectin. That was in 1978, but it was a few years later before the two men met.

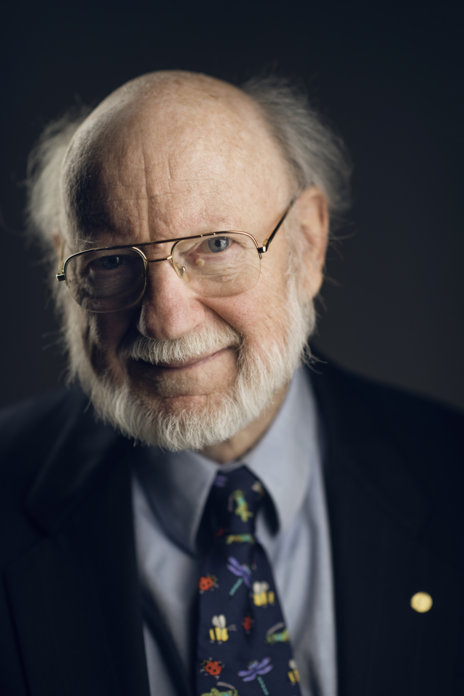

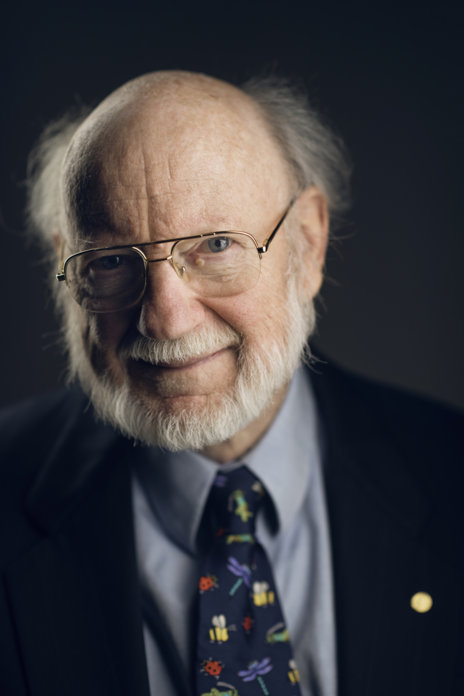

Nobel laureate William Cecil Campbell (known as Bill) was born in Derry in June 1930 and grew up across the border in Ramelton, County Donegal. He tells the story that there was no maternity hospital in Ramelton so he arrived in the occupied part of the land and grew up in the Donegal town.

DONEGAL'S GREATEST SON: William Campbell

His father had a run-in with the local school principal and hired a teacher to educate his sons at home. At the age of 13 he attended Campbell College as a boarder. During World War 2 the college was relocated to Portrush and Campbell boarded there for two years. When Campbell, the college, resited to Belfast, Campbell the boy returned to a Ramelton.

An early interest in livestock may have been sparked by his father, a farm supplier who kept cattle and sheep, but a turning point came at the age of 16 on a trip with his boarding school to an agricultural fair. He returned with a fascination for parasites and worms and their removal from farm livestock. Bill studied zoology at Trinity College, Dublin, graduating with a first class honours degree in 1952. He then gained a Fulbright scholarship to study in the USA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he earned his PhD in 1957 for his work on liver fluke, a parasitic infection in sheep.

Campbell went straight from university to a job at Merck Institute for Therapeutic Research, which grew into a 33-year career, during which he became a US citizen in 1964. At Merck one of his first discoveries, through trial and error, was how to successfully freeze parasitic worms for experiments, which saved scientists having to keep livestock to gain fresh samples. He became one of the leading researchers at Merck.

Near the tenth tee on a golf course outside Tokyo there is a plaque which tells waiting golfers that a lump of clay retrieved nearby may have saved the sight of millions. It was here that Satasho Omura was waiting to tee off in early March 1975. He opened his wallet and took out a small plastic specimen bag. He filled it with soil and sealed the bag which he placed in his golf bag, took out a one iron and proceeded to continue to play his round of golf.

He was a Kitasato University Professor Emeritus from 1973. Earlier he was a visiting professor at Wesleyan University in USA where he consulted the chairman of the American Chemical Society, Max Tishler, at a Canadian international conference for sponsorship. Finally, they succeeded in acquiring research expenses from Merck & Co., a leading American research company and he returned to Japan to continue his research.

Bill Campbell takes up the story.

“On 9th May 1975, there was a mouse in a mouse-box in a laboratory. It had been purposely infected with worms—but not enough to cause illness. On that day its diet was altered—some liquid was stirred into its regular food. And the mouse ate that food for almost a week. Then its normal diet was restored. And about a week later it was discovered that its worms had gone! From that moment a train of events was set in motion. It would lead, some years later, to an advance in medical and veterinary science, and that, in turn, would lead to practical changes in the management of parasitic disease. To a very large extent the drug ivermectin was brought about by simple science. It was not conventional science; it was not obvious science; but it was simple science.”

The liquid that had been added to the diet of that mouse had been fermented by a bacterium that was one of hundreds of microbes that had been sent to Merck & Co. Inc. by Satoshi Ōmura and his team of chemists and microbiologists at the Kitasato Institute in Tokyo. This led to the development of ivermectin which was used to control heartworm in dogs and various worm infections in horses and other livestock.

But this was not the reason Bill was chosen for the Nobel award. He realised that ivermectin might work for humans too and carried on its development successfully.

In 1987, nine years after the latter discovery, he convinced his employer Merck Research Laboratories that since they had made a fortune from veterinary pharmaceuticals, they should distribute the human drug free of charge as countries in Africa and South America could not afford it. This led to saving millions of lives in the developing world in the process. As a result, the World Health Organisation moved from treatment to elimination of river blindness, a parasitic disease which afflicted much of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Omura and Campbell’s discovery has contributed dramatically to reducing the number of people plagued by “stigmatising and disabling symptoms” of river blindness (intense itching, skin discoloration, rashes, and eye disease often leading to permanent blindness) and elephantiasis (a gross enlargement of an area of the body).

Campbell’s 90th birthday was celebrated last weekend at a small family gathering in Boston, but it also coincided with publication by the Royal Irish Academy (RIA) of his memoir ‘Catching the Worm’ – a story of the discovery of ivermectin for veterinary use in livestock to eliminate parasites, and then its subsequent adaptation in 1978 for use in humans.

A bronze statue was to be unveiled in Ramelton but that has been postponed due to the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic.

But the story doesn’t end there. Australian research has found that the drug could greatly inhibit the replication of the virus and clinical trials are currently being conducted by Australian universities. Daniel O’Donnell and Packy Bonner might have to move aside if Bill Campbell becomes Donegal’s best known man.