Bloody Sunday 1920 earned its name. Unlike the Bloody Sunday of 1972, there were two bloodbaths occurred on Sunday 21 November 1920.

In the morning the first batch of killings were carried out under instructions from Michael Collins. A hand-picked group of IRA Volunteers assassinated fifteen members of what was known as the ‘Cairo Gang’ – undercover British intelligence agents, living in and working from South Dublin. When news of the killings filtered through, several other British agents in the Dublin area fled to the security of Dublin Castle.

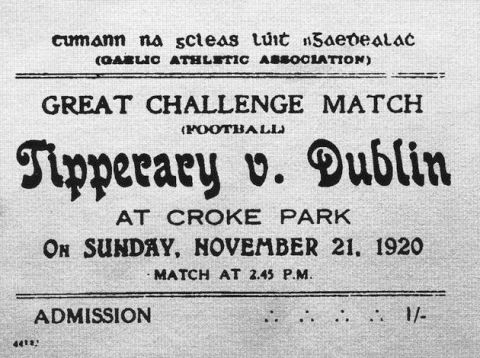

In the afternoon, the second round of killings happened. These occurred at Croke Park that afternoon and are often referred to as ‘retaliation’ by the British forces for the elimination of the Cairo Gang in the morning. However, on its website last week the BBC claimed that “The British authorities suspected some of the gunmen had disappeared into the crowd at Croke Park, so armed police were deployed to block all the exits and search thousands of spectators.”

I haven’t heard that explanation before. If it’s true, it shows the British authorities were more than a little dim. How did they hope to locate their suspects among the thousands of spectators, and what did they think the thousands attending the game would have been doing while they conducted their search?

Whatever the thinking, following a flare signal from a small spotter plane overhead, the British military fired into the crowd and at players on the field. In all, fourteen people were killed, including three schoolboys aged 10, 11 and 13, and one player on the field, Mick Hogan, after whom the Hogan Stand in Croke Park is named.

There are those who see the morning and afternoon events as providing some kind of gruesome balance: the IRA killed British agents, the British military shot people in Croke Park. But that’s a false equivalence. The British agents killed were British spies in Ireland, working to kill IRA Volunteers. In contrast the killings in Croke Park were random, as the deaths of the three boys clearly indicates.

In the film Michael Collins, the IRA men chosen to carry out the assassinations are shown as having to nerve themselves to go through with the killings. Most of us understand that – the taking of human life is a terrible, final thing. But once a society or country commits to war, that’s what people do. The Cairo Gang were part of the British forces in Ireland, intent on crushing republicans and Ireland’s drive for independence.

In contrast, those in Croke Park were overwhelmingly people not involved in the military conflict. They were innocents, mowed down while they attended a sporting event in their own country.

Judging by the number of TV and radio programmes devoted to Bloody Sunday 1920, I would guess people in the south of Ireland are still horrified by the slaughter at Croke Park and see the elimination of the Cairo Gang as a justified act of war. How odd, then, that so few in the south appear to see the Bloody Sunday events of 1972 as equally monstrous.

Again in 1972, armed British soldiers fired into a crowd of innocent Irish civilians and killed fourteen. In the south there is, naturally, sympathy with the families of those killed; but there is no demand that those who ordered the killings and/or carried out the killings should be charged with murder. On the British side, there is even indignation that any of those guilty be held responsible.

Which is astonishing, when you think of it: nearly fifty years after Derry’s Bloody Sunday, not a single British soldier has been charged, let alone punished for what happened. Yes, David Cameron squeezed out an apology after more than thirty years, but how absurd is that? Supposing your neighbour came into your house one afternoon and killed several of your family, lied that your family was armed when they were totally defenceless, and eventually, decades later, confessed that it was a bad act he had done and says very sorry. No charge, no jail sentence for the killings.

Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised. The history of British involvement in Ireland, including Bloody Sunday 1920 and Bloody Sunday 1972, shows that British forces in Ireland can kill at will, secure in the knowledge that their superiors will always find a way to protect them.