THE First Minister has suggested Northern Ireland’s centenary could provide an opportunity to examine the creation of a single education system in the region. "2021 can be an opportunity to re-examine the past decisions that shaped Northern Ireland," she said. “Lord Londonderry’s early proposals to create a common education system were not implemented. Is 2021 the time to re-start that debate?”

The first Ulster cabinet was modelled on Westminster. It had six ministers. Sir James Craig was Prime Minister. Born in Belfast, educated in Edinburgh, he had been a stockbroker, a military officer and had held minor posts in the Westminster government. He was competent, a strong Protestant and a stronger Unionist. Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, Edward Archdale, a native of Fermanagh; Minister of Finance, Hugh Pollock, viewed as able and moderate; Minister of Home affairs, Sir Dawson Bates, seen as an unashamed bigot; Minister of Labour, John Andrews, a wealthy landowner who would succeed Craig as Prime Minister only to be undermined; Minister of Education, the Marquess of Londonderry.

“I have 109 officials, and as far as I know there are four Roman Catholics, three of whom were civil servants turned over to me whom I had to take when we began.”

Sir EM Archdale, the Minister of Agriculture, former Grand Master of the Irish Orange Lodges, had probably the most narrow pro-Protestant viewpoint. He said on 31 March 1925: “I have 109 officials, and as far as I know there are four Roman Catholics, three of whom were civil servants turned over to me whom I had to take when we began.”

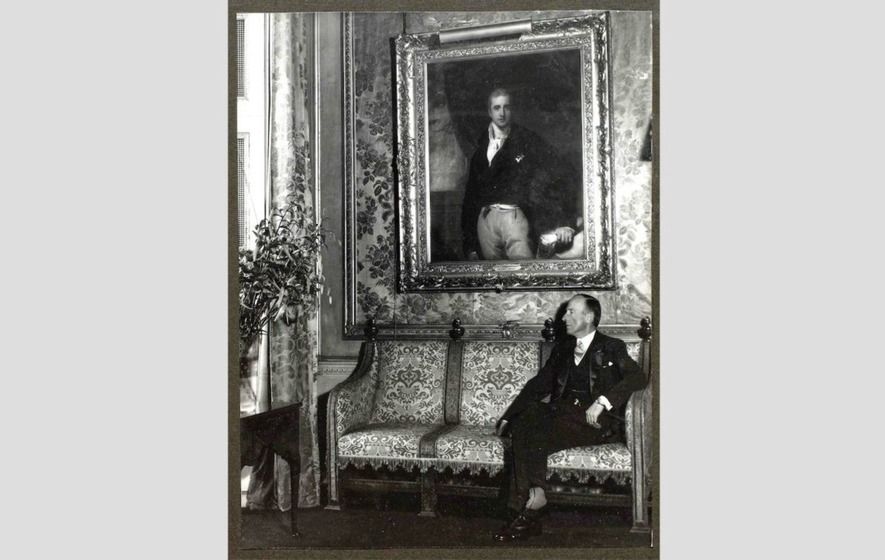

Given the lack of style in the other cabinet appointments, the presence of Charles Stewart Henry Vane-Tempest-Stewart, seventh Marquess of Londonderry, was sensational. Educated at Eton and Sandhurst, with a career in the Royal Horse Guards, he had held a minor cabinet post in Westminster. Why such an aristocrat should wish to serve in a provincial government baffled many. It was certainly not for economic reasons. He became a member of the Senate and Education Minister while representing Northern Ireland in the House of Lords.

However, it might be argued that Londonderry had too many irons in the fire. He had to oversee the family coal mines in Durham and properties in England and Ireland while acting as spokesman for Ulster in the House of Lords. He was absent from Belfast for long periods of time meaning that decisions were often made by senior civil servants. The newly formed state had inherited the National School system. Formed back in the 1830s, the intention was that children of all denominations were to be taught together in the same school with separate religious instruction. In effect, parents chose to send their children to schools catering for children of heir own religion.

CONTROLLED FROM DUBLIN

Lord Londonderry wanted to create a non-denominational system with local education committees controlling schools rather than managers. He instructed Robert Lynn to set up a committee and put forward proposals for a new education system.

Lynn was a prominent Orangeman, Unionist MP for West Belfast and editor of the Northern Whig, a strongly unionist daily newspaper. This was in September 1921 when all educational affairs were still being controlled from Dublin.

Between 1936-38 Unionist Lord Londonderry made 6 visits to Nazi Germany & attracted the popular nickname of the "Londonderry Herr" meeting Hitler, Hess, Goering, Himmler, Papen, Ribbentrop and many other senior Nazis of the time-here’s Nazi gift on display at Mounstewart today. pic.twitter.com/M48P4yNh1H

— Seán de Náipír (@Seanofthesouth) May 8, 2020

Despite several requests the committee was shunned by Catholics, which was hardly surprising given that a civil war was raging throughout the north. When we reflect on the imposition of various Special Powers Acts permitting home searches without warrants, summary jurisdiction given to magistrates and the introduction of the death penalty, you cannot with any credibility treat a Catholic citizen as a potential traitor and simultaneously convince him that the law-enforcement system is impartial.

The Protestants viewed the Catholics as traitors, the Catholics saw the Protestants as oppressors. In the Protestant view the Special Powers Acts were objectionable only to those who were contemplating rebellion or disloyalty, so the Catholics in opposing the Special Powers Acts had affirmed their guilt.

]Lynn declared that he would honour the views of Catholics but many doubted this. In May 1923 as the final report of his committee was awaited he told the Northern parliament his views on teaching Irish: “Teaching Irish in schools is purely a sentimental thing. None of the people who take up Irish ever know anything about it. They can spell their own names badly in Irish, but that is all. I do not think it is worth spending any money on it.”

The Lynn committee had extensive representation from both Church of Ireland and Presbyterian authorities. Religious instruction was included. “The churches should prescribe the programme of religious instruction for their own children either separately or in agreement amongst themselves. It is hoped that a common scripture programme can be agreed upon for the religious instruction of children belonging to all Protestant denominations.”

The Presbyterian delegation singled out one subject other than religious instruction as being pernicious – history – “owing to the difficulty of having unbiased history taught in primary schools, the subject should be forbidden”.

LYNN REPORT

Published in June 1922, the Lynn interim report formed the basis for Lord Londonderry’s educational reform act. They identified three types of school. Class I schools would be elementary schools built by local rates in combination with the Ministry of Education grants and existing schools handed over by their previous managers to the local primary educational committees. They would be entitled Public Elementary schools and referred to as ‘transferred’. Class II elementary schools would be those schools for which special school management committees were formed composed of two representatives of the local primary school committee and four representatives of the school patrons. They became known as ‘four and two schools’. Class III schools were to be those schools whose managers wished to remain entirely independent of local government authorities. Class II and III schools became known as voluntary schools.

All of the schools were to continue to have the salaries of the teachers paid. Class I schools had the cost of furnishing, heating, maintenance and repairs paid from the local rates. Class II schools were to have half these costs paid from the local rates while Class III schools were to receive no aid from local rates.

This classification endured until after the prorogation of Stormont In the 1970s Lord Londonderry moved at speed. His draft bill was discussed at cabinet in February 1923, introduced to parliament in March and on the statute books by mid-October. He ignored parts of the Lynn report. In a letter to the Church of Ireland Bishop of Dromore he wrote: “And now let me come to that other type of instruction which I shall call for the sake of clearness, not religious but moral instruction... Such teaching must by necessity be absolutely undenominational... It cannot include reading from the pages of the Bible itself.” The 1923 act also prohibited the religious affiliation of a teacher being taken into account when they were being considered for a post.

It was only then that representatives of the main Protestant churches looked closely at the bill. Under pressure Craig relented and allowed amendments in 1925. Londonderry resigned in 1926.

The church authorities persisted and in 1930 clerical representation on committees was permitted. Under section five of the Government of Ireland Act the state could not endow any religious body and as such the new system had to be non-denominational. I don’t know what Mrs Foster has in mind but it strikes me that the present Minister of Education will be able to bring in whatever reforms are required now that he is no longer preoccupied with this year's selection procedure.