A NUMBER of origin stories weave the tale of how a mythic group of seven Irish-born athletes who won 20 medals representing the United States at the 1896-1924 Olympic Games – the Irish Whales – acquired their colourful name.

One account, by US Athletics team official Dan Ferris, describing events aboard the ship which brought the US team to the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, may be the most entertaining.

“Those big fellows all sat at the same table and their waiter was a small chap,” he said.

“Before we reached Stockholm he had lost 20 pounds, worn down by bringing them food. Once as he passed me he muttered under his breath: ‘it’s whales they are, not men.’’’

There was no doubting the massive physical presence of these unique men.

Pat McDonald from Doonbeg, Clare, was six foot, six inches, weighed over 300 pounds, and bore the unlikely nickname of ‘Babe’.

Later in life, he became known as ‘The Statue of Liberty of Times Square’ where he had the position of traffic controller for the NYPD for almost 30 years.

Paddy Ryan from Pallasgreen, Limerick, was only an inch shorter than ‘Babe’ McDonald and a mere five pounds lighter.

The great Matt McGrath from Nenagh, Tipperary, who became widely known as the ‘Prince of Whales,’ was almost as wide as he was tall, and frequently described as ‘a wedge of a man.’

The very first of the Whales to come to prominence, James Mitchell from Emly, Tipperary, was a behemoth of a man with a huge handlebar moustache to match his imposing physicality.

Mitchell first came to the United States with the so-called GAA ‘Invasion Tour’ of 1888 and went onto virtually monopolise throwing events in the country for a decade.

The illustrious group was completed by the imperious Martin Sheridan from Bohola, Mayo, three-times Olympic gold medal winner John Flanagan from Martinstown, Limerick, and Con Walsh from Millstreet, Cork.

With the exception of Walsh and Ryan, all were members of the New York Police Department.

Some suggest that the blue tunics they had to wear as part of their job gave them the appearance of large mammals, another possible creation story for their collective name.

While all the Irish Whales had learned to throw weights in Ireland, to some degree, it was in the red-hot furnace of competitive athletics in the United States that they honed their remarkable skills. And while all were talented throwers, Martin Sheridan, in particular, may have been the best ever athlete produced by Ireland. Sheridan was effectively a decathlete before the term was invented.

When the 1896 Intercalated Olympic Games are included in the roll call of honour, he won seven Olympic gold medals in total. So impressed was the King of Greece by Sheridan’s performance in 1906, he commissioned a statue of the Irish athlete and presented him with a commemorative vaulting pole, still on view in the Martin Sheridan Community Centre in Bohola, Mayo.

The list of the Irish Whales’ achievements is long and illustrious but, perhaps, their greatest hour came in the hammer throw competition at the highly politically charged 1908 Olympic Games in London.

The games, virtually a war by proxy between the United States and Great Britain, were marred by a succession of quibbles between the countries, some real and others imagined.

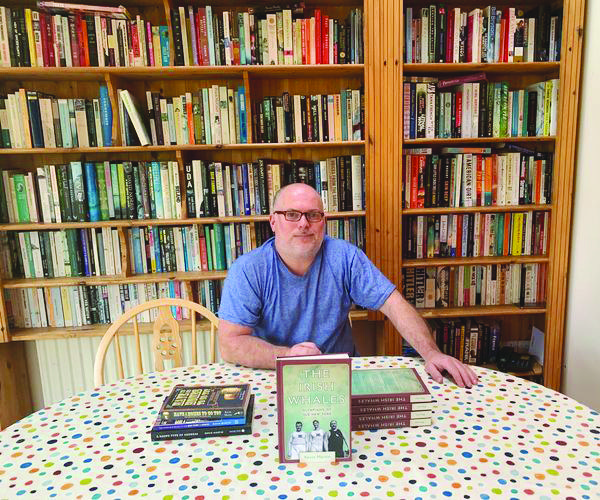

The Irish Whales, super book from Kevin Martin about the 1st Irish Olympians, available now in Tertulia bookshop, we can post, special postage 2.95 email tertuliabookshop@gmail.com and check out our new website https://t.co/lWuAavgFGH #abookshoplikenoother #cuboardunderthestairs pic.twitter.com/EQMNHxOdO0

— TertuliaBooksWestport (@TertuliaBooks) September 5, 2020

Further heat was added to the mix for those Irishmen representing the US and Canada, given as there was no official Irish team. Those who lived in Ireland and wished to be part of the games had to do so under the British flag.

Martin Sheridan, who held particularly strong nationalistic views, encouraged the Irish athletes on the American team to win it for the native sod. Sheridan’s imprecations were answered in the best manner possible when Irish-born athletes completed a clean sweep in the hammer throw.

John Flanagan took his third consecutive gold in the event, becoming the first athlete to do so in any discipline at the Olympic Games. Matt McGrath took the silver, while Con Walsh, representing Canada, took the bronze.

In a discipline requiring strength and finely developed technique, this was a declaration of intent.

The great Martin Sheridan took two golds for discus throwing, one in the conventional version and the second in the subsequently discontinued Greek throwing style.

The 1908 London Olympic Games are also known for a then-unique diplomatic breach.

As the American Olympic team passed King Edward VII in the Royal Box during the opening parade, the flag carrier, Ralph Rose, did not dip the US colours. Who said what to whom has long been an issue of debate. What is not disputed is that the flag did not dip, much to the annoyance of the British.

The story goes that one of the Irish American athletes told Rose to withhold the gesture with the order: “This flag dips to no earthly king.”

Whether or not the immortal words were uttered by Matt McGrath or Martin Sheridan, as has been variously claimed, the action set a famous precedent.

Central to the success of the Irish Whales was the role played by the Irish American Athletic Club of New York, subsequently known as the IAAC.

While the famed organisation, originally established in 1904 by Limerick man PJ Conway, did not confine itself to those of Irish ethnicity, it provided a platform for Irish emigrants to develop their talents in a collegial environment when they were only grudgingly accepted in such knickerbocker/WASP bastions as the New York Athletic Club, if allowed past the portals in the first instance.

Jewish athletes Able Kiviat and Myer Prinstein were prominent members of the IAAC, while Celtic Park was also the home ground of John Baxter Taylor Jnr, the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal.

The IAAC had its home in Celtic Park in Queens. Its symbol was a winged fist adorned with American flags and shamrocks under which the club motto Láimh Láidir Abú (Strong hands forever) was detailed.

Tragically, on March 27, 1918, Martin Sheridan died on the eve of his 37th birthday, most likely as one of the very first victims of Spanish Influenza, a global pandemic which killed more people than World War One and took the youngest and fittest first.

At the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Matt McGrath set a world record mark in the hammer throw, which lasted for 24 years. Moreover, McGrath was to go on and win a silver medal at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris at the remarkable age of 47, still the oldest athlete ever to win an Olympic medal in track and field, a record unlikely to be broken.

The Paris Olympic Games were to prove the swan song for the Irish Whales, but the hammer throwing torch was passed on to Dr Pat O’Callaghan, who went on to win gold in the hammer throw at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam and again at the 1932 iteration of the championship in Los Angeles.

Fittingly, John Flanagan, who returned to Ireland to take over his family farm in 1911, helped the Cork native in his preparations. Flanagan had added to his long list of achievements by taking the Irish hammer throw title in 1911 and 1912.

The Irish Whales were emblematic of the success that hard work and self-discipline could help Irish Catholic emigrants achieve. They were role models for an ethnic group gradually acculturating and assimilating into American society.

Their story was part of the warp and weave of the Irish emigrant/immigrant story. They were fine representatives of their native country when a ‘cult of masculinity’ was sweeping America.

The Irish at the time also famously had considerable success in the sports of baseball and boxing, but the ‘Irish Whales’ were unique because they strode a global stage.

While their chosen sport did not bring economic self-advancement in the way that professional sports did later for others, their success added to the cultural capital of the American nation.

The records set by the ‘Irish Whales’ in their respective disciplines have long been surpassed. They have largely faded into the mists of time. Though they may have become more mythical than real, their likes will never be seen again. We should never forget them.

Kevin Martin, an Ireland-based cultural historian, is the author of several works. ‘The Irish Whales’ is published in the US by Rowman & Littlefield and is available online from Amazon and Barnes & Noble