Dan O'Neill was one of the brightest artistic stars West Belfast ever-produced.

And yet his once stellar reputation and his very much still-stunning paintings have languished in the shadows since his untimely death in 1974.

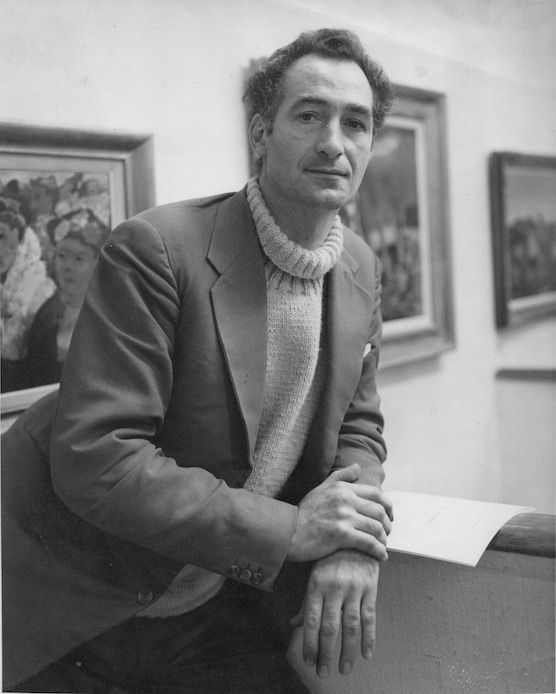

It wasn't always thus: In the fifties and sixties he was feted with George Campbell and Gerard Dillon — a Clonard neighbour – as the boldest of the Belfast Boys, a posse of local artists bringing their own unique Ulster sensibility to the burgeoning Irish arts scene. O'Neill stood six feet three inches tall; every room he entered was lit up by his presence and his striking good looks, every brush he touched to canvas sprung to life with soaring imagery.

Self-taught, his training was as far from the Slade School of Art and as socially distant from the Ufuzzi Gallery as you're likely to get. He took inspiration from the great masters of the renaissance via the Central Library book stacks and honed his burgeoning talent on the back of his Belfast City Tramcar wages card.

And yet, the works he produced were ethereal, evocative, sensual, radiant and ravishing. While Dillon, a gay man in the suffocating stranglehold of Northern unionists and their censorious clerical counterparts in the Free State, dared only to signal his regard for the male form, Dan O'Neill romanced the canvas.

In the view of family and friends, he loved women. And it showed both in his passionate portraits of the three women who shared his life over three decades and in his reverence for his female 'sitters'.

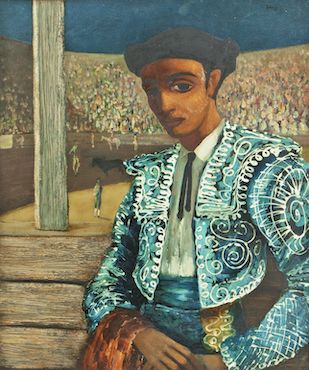

MOURNFUL: 'Oh Danny Boy' by Dan O'Neill

Coming of age in the Belfast Blitz, he knew what it was to witness a city in flames and when the city exploded again in 1969, he responded both by painting Bombay Street alight and by attending meetings supporting the civil rights struggle.

How could it be otherwise? After all, his home in Dimsdale Street abutted Mackie's Factory. Famously, Protestant employees had to pass the homes of Catholics to clock in daily at a factory which didn't allow Papishes about the place.

In her revelatory new book, 'Daniel O'Neill Romanticism & Friendships', Karen Reihill saves the blushes of the West Belfast community which has all but wiped Dan O'Neill from its memory. In this the centenary year of his birth, she recalls his formative years, his thirst to paint, his chronic and debilitating alcoholism which surely shortened his life, his frequent hospitalisation following bouts of depression, his prolific output and, mo léan, his death in penury.

#MustRead...#Dan O’Neill ... enjoy Karen Reihill’s new tome on Northern Ireland artist Dan O’Neill. Karen spent 10yrs researching this book. Enjoy. @colin_davidson @shonacunningha4 @MiriamOCal @mandy_mcauley @Donald_Teskey pic.twitter.com/pPy9GJc3o8

— Eamonn Mallie (@EamonnMallie) November 28, 2020

If there is a Book of the Year award in West Belfast, Reihill's monograph would win hands-down. Not just for its thorough telling of the tale of Dan O'Neill with only meagre historical resources to draw on but also for reproducing scores of mini-masterpieces by the artist, including his later moving self-portraits depicting himself as a tearful clown.

Everybody loves a drink but nobody likes a drunk goes the cruel old saw. His behaviour to others did not always merit an A-Star.

So perhaps that's why there is no Dan O'Neill Gallery in West Belfast to match his sparring partner's Dánlann Gerad Dillon in the Cultúrlann; no Dan O'Neill bridge across the renovated Springfield Road dam (as close to his old stomping ground as you're likely to get) to help the weary cyclist heading to the John Luke Bridge over the Lagan. Jesus, they even have a restaurant in Co Antrim — the magnificent Clenaghan's — dedicated to that artistic sun god Sir John Lavery who preceded O'Neill by half a century. Could we not rise to a Dan O'Neill coffee house?

Failing that, can we put him on the A Level syllabus or have a Dan O'Neill painting school during the summer Féile?

After a turbulent and uneven career - including a decade in exile in London in the swinging sixties — Dan O'Neill returned home to a city torn apart. He ended up, haunted by the drinking demons, living alone in an Eglantine Avenue flat, and, though exhibiting as late as Christmas 1973 in a group show, died without two farthings to rub together. After, apparently, a night on the tiles, he choked on a chicken bone and died on 9 March 1974, at the age of 54 - that period of mid-life when the truly great artists are only hitting their stride.

There was, of course, a lot going on in Belfast in 1974. So let's forgive the generation or two which came before us for being too busy with the affairs of life or death to spare a thought for the genius of Dan O'Neill. But the continued amnesia in a community which understands how God-awful hard it was for a guy from Dimsdale Street to rise to the top of his artistic trade; A community which in recent years has prided itself on paying homage to those who moved among us and then left their mark — good to see you again, Mr Connolly.

FORGOTTEN: Dan O'Neill's 1949 'The Matador'

That disgraceful omission, that's on us.

So moore power to Karen Rehill then. Not only has she penned the first biography of this brilliant Belfast Boy but she has also given us the opportunity to put right a fifty-year injustice to the memory of our grandest portraitist.

For with her diligent sleuthing into the life of Daniel O'Neill, Karen Reihill inspired the curators at the Farmleigh Gallery in Dublin to mount an exhibition of his works - delayed due to Covid, of course but surely it will rise again.

And then, what shows in Dublin can, surely, exhibit in West Belfast?

Karen Reilhill's masterpiece Daniel O'Neill Romanticism & Friendship is available from An Chultúrlann bookshop, An Ceathrú Póilí, price £22.

STRIKING: Artist Dan O'Neill