HUGE pressures on public health followed the rapid population increase of Belfast, increasing from approximately 25,000 in1808 to almost 100,000 in 1847.

Large numbers lived in severely overcrowded, unsanitary, poorly ventilated slum tenements. High levels of disease and sickness were prevalent with low life expectancy and high levels of infant mortality; the average age at death being nine years of age in 1850.

Consequently public health became the primary concern with the medical profession in the mid-19th century, as the effects of industrialization, housing conditions, fever and cholera epidemics and the ravages of the Great Irish Famine took their toll.

The highly polluted open Blackstaff River was the outcome of appalling public sanitation, and the absence of waste and sewage disposal networks in the town.

“The Abomination of the Blackstaff” was a term used by a contemporary newspaper to describe the sanitary evils, disease, illness and deaths inflicted on the population.

Originating in the Black Mountain the Blackstaff emerged at the Bog Meadows heading along the line of today’s Boucher Road in the direction of the Broadway roundabout, then towards the railway station at Great Victoria Street in the direction of Linenhall Street towards the later Ormeau Gasworks site, finally discharging into the Lagan.

The river became a notorious public health hazard in mid-19th century Belfast having become an open cesspool for raw sewage, toxic waste from factories, textile mills, hospitals, and used for dumping anything and everything by the inhabitants from house-hold-rubbish to, human excrement, dead animal carcasses and more.

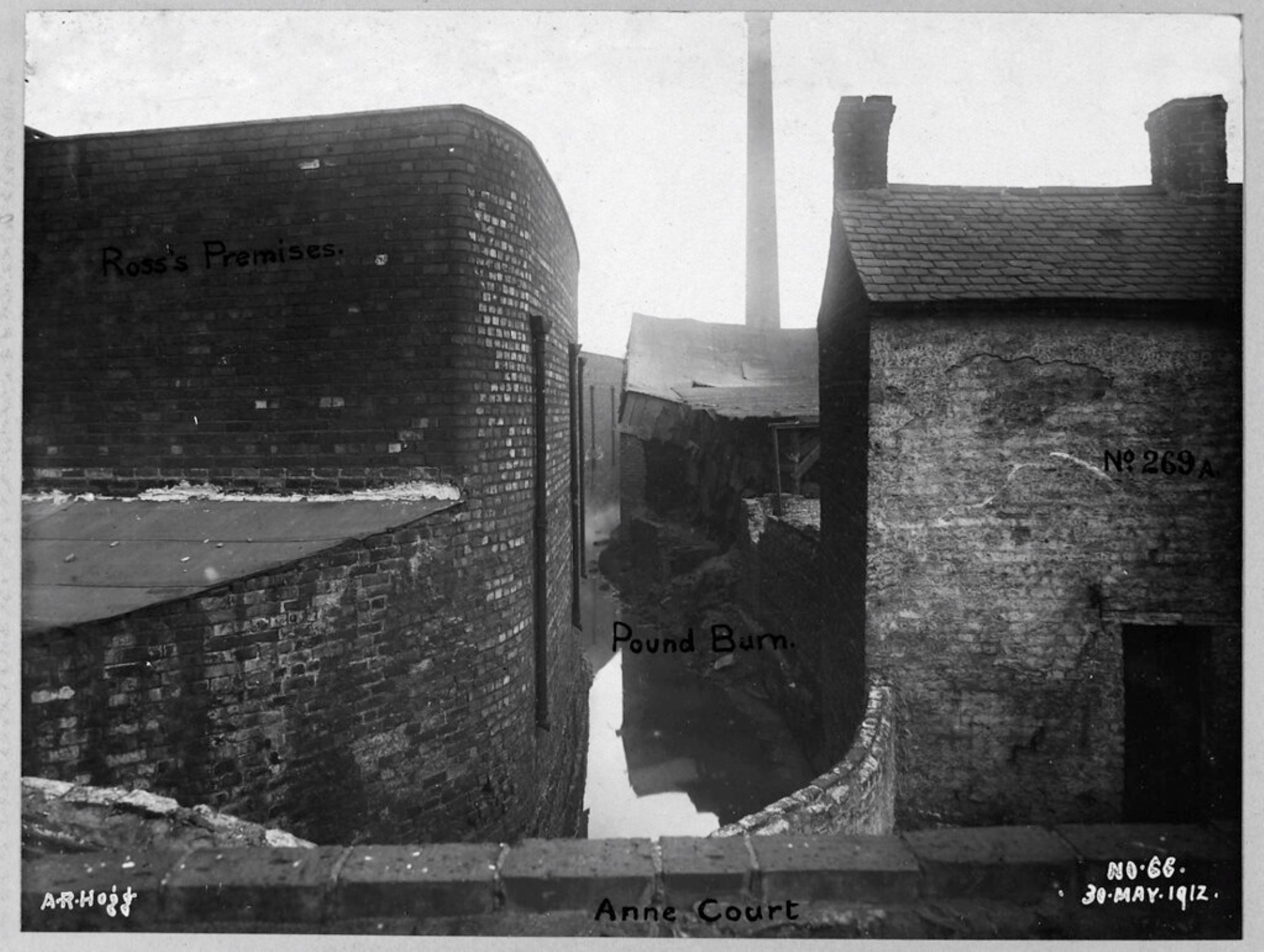

It was made worse by a well known tributary stream, the Pound Burn, which connected with it at the end of Durham Street, flowing from Barrack Street and the Falls Road direction. It likewise was polluted with toxic waste from mills and raw sewage and rubbish from the inhabitants of adjacent districts who habitually pitched everything into it, including human excrement and dead carcasses.

One contemporary observer in 1854 claimed to have seen one day “13 dead cats and a suckling pig floating down the stream.”

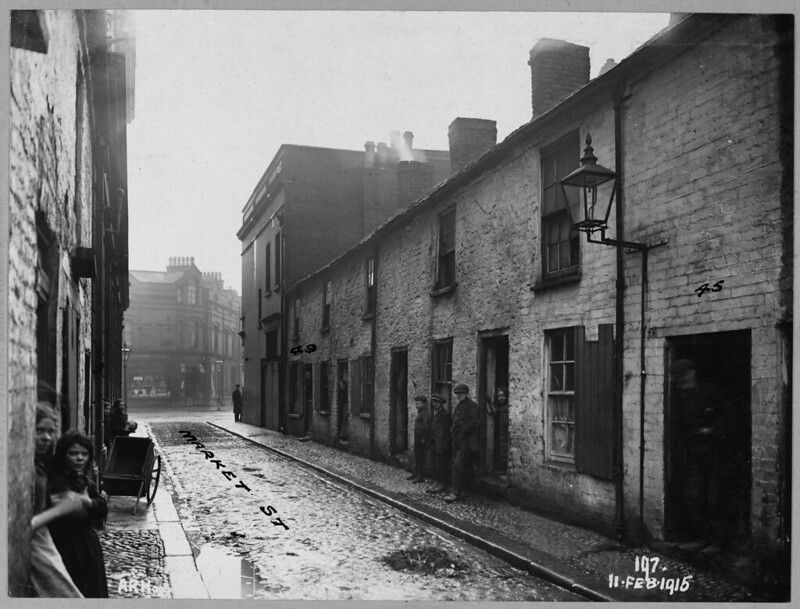

Hamill Street Area. Anne Court. Pound Burn Stream, Ross's Mill, 1912 Courtesy The Deputy Keeper of the Records Public Record Office of Northern Ireland LA/7/8/HF/3/66

These practices made for the greater spread of contagion and disease of typhoid, dysentery and periodic epidemics of typhus fever and cholera. In his ground breaking report, ‘The Sanitary State of Belfast; With Suggestions for Its Improvement 1852', Dr Malcolm stated: “Through a populous and comparatively central portion of the town flows a black, foul, and filthy stream, a parallel for which will not be found in Ireland — Thick with decayed animal and vegetable manner, odorous with the foulest stench, it rolls along its abominable loathsome flood, tainting the air with deadly poison, and spreading round the seeds of disease on every side. The fatal potency of this devil’s broth is known from the fact that, whenever epidemic fever breaks out in our town, its greatest virulence is found to exist in the neighbourhood of the filthy Blackstaff...”

The neighbourhoods referred to were contained within the College Ward (Durham Street, College Square areas) and Cromac Ward. The health impact of the Blackstaff on both areas was such that they had the greatest number of deaths from ‘all causes’ in 1849 and in the months of June, July and August, 1849, when the cholera epidemic was at its worst these same districts had the ‘largest mortality rates’.

On the final part of its journey the Blackstaff flowed towards the Joy family’s Paper Mill which was particularly problematic in the 1840s-50s. The Mill’s dam and weir could interrupt the natural flow of the river to the Lagan outlet with its tidal waves, causing blockages and build up of raw sewage and toxic waste and the creation of a large toxic cess pool by the river when its banks overflowed due to the obstruction.

Toxic fumes and gases from the cesspool were highly injurious to the heath of the inhabitants in the nearby Cromac district, which also suffered from terrible flooding during the winter as the Blackstaff burst its banks from the seasonal rains. The flooding of the Blackstaff was a characteristic feature of town life bringing hardship and sickness to the homes of the poorest inhabitants that could be immersed in flood water up to three feet deep for many hours.

The Belfast Sanitary Committee in December 1849 revealed the public health dangers; 200-400 houses (literally thousands of family members) were subject to its winter floods two to three times annually of a,“...filthy semi fluid matter of the most offensive description; and in summer hundreds of people are sent to a premature grave from the effects of the noxious effluvia which exhale from the accumulated filth which has been collected by the obstruction of the free course of the river by the weir at the Paper-Mill.”

Picture 1935. The Belfast Gasworks as seen from the bottom of the Ormeau Road, with the Blackstaff River on the left. Anonymous Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Town Council was responsible for dealing with town planning and sanitation issues but it was mainly represented by individuals with strong commercial and industrial interests. With their positions they represented a ‘new form of class power’ in the town that raised questions about whether their conflicting personal interests and civic duties of office allowed for council business conducted in the best interests of Belfast and all its citizens.

Two Town Improvement Acts were available to address the problems of the Blackstaff River and tributaries including the Pound Burn stream. The 1847 Act allowed for the compulsory purchase of land for drainage and the abatement of the Blackstaff problem for up to three years. The 1850 Act allowed the Council up to two years for diverting and culverting the Pound Burn and Blackstaff and authorised the council power to borrow £15,000 for the purpose so long as the work was done within the two years. Both came to nothing as all parties could not come to any agreements.

Criticism of the council became a recurring theme in these years for its apparent ineptitude with resolving the ‘Blackstaff Nuisance’. The Newsletter on 21st April 1854 asserted that the failure to abate the Blackstaff problem was due to the town council’s “mismanagement”, their failure to utilize the powers of these Acts effectively and their failure in negotiations with the Joy family over the purchase of the Paper Mill dam and weir.

On October 30th1854 the public took a case against the Town Council for being responsible for turning the Blackstaff River into a cesspool, an open sewer and a public heath danger. Belfast Magistrates upheld the town council’s right to use the Blackstaff as an outlet for the town’s sewage as it was granted a right to do so by an Act of Parliament. The Town Council did not deny the outcomes to public health but argued that the Act of Parliament entitled them to make sewers “into any river or water course” and that they complied by making the sewers into the river Blackstaff and Pound Burn, astonishingly adding, “in as much as they had ‘only killed off the unfortunate inhabitants who were poisoned during the visitation of cholera by the fumes of their corporate stenches’, in accordance with the Act of Parliament, they were not amenable to a prosecution.”

An entirely new approach was taken in April and May of 1854 to deal with the public health dangers of the Blackstaff and Pound Burn by the Town Council. On April 28th the council generally agreed that the two issues to be addressed were the Pound Burn Stream and the Blackstaff through the construction of additional sewers and to prevent the dumping of toxic waste from neighbouring factories, mills and the Workhouse Hospital, where fever and cholera patients were treated, into sewers that discharged into both water courses and to address the discharge from the Pound Burn at its ‘point of connection’ with the Blackstaff.

A plaque marks the spot where the Blackstaff enters the Lagan at the Gasworks site

It transpired that of fifty parties owning property adjacent to the Blackstaff not one consented to the council proceeding with attempts to resolve the problems associated with the river. The Council meeting of May 12th agreed to deal with ‘wider issues’ of sewage and sanitary improvement across the town rather than negotiate with leaseholders and land owners around the sites of the river Blackstaff and the Pound Burn, bearing in mind the enormous costs and conditions asked for by Messrs Joy for the Paper Mill weir and land and other property owners.

Most of it was later culverted and built over in the later nineteenth century when Belfast developed from town to city status in the 1880s. Decades later the plans for the diversion of the polluted Pound Burn had still not happened, the reasons being unclear, although there were suggestions of inertia over a long period by the Town Council, and resistance to diverting the course of the Pound Burn away from the Black staff and alterations to the River Blackstaff because of a loss of water supply to their industry.

A significant cause of the pollution of the Blackstaff had been addressed in the late 1850s and after by diverting the immense polluting discharges from the Workhouse away from the Blackstaff and into the Lagan; this together with new drainage tunnels and improved sewerage networks across the town.

Dr Malcolm’s 1852 report had been pessimistic for the future of sanitary reform in Belfast, “Any permanent improvement of this extensive locality cannot be attempted with propriety until this monster grievance be removed. But the cost of remedial measures deters from action; and the difficulties of a mutual settlement as to the amount of claims prevents anything being consummated,” adding, “No; the sanitary cause, to be effectual for its object, must be continuously agitated; AND SANITARY OPERATIONS MUST NEVER STAND STILL, AS THE SOURCES OF SANITARY EVILS ARE INCREASINGLY AT WORK.”

Brendain Muldoon© 2021