EOGHAN Daltun is Dublin born and bred, but he got the call of the wild. He soon became convinced that he wanted to move his family out west, and during one family holiday in Cork’s Beara peninsula in 2009 he found what he’d been looking for. A farm clinging on to the Atlantic.

“Within seconds, I knew with absolute clarity that this was where I wanted to spend the rest of my life. It was a case of love at first sight,” he writes in his acclaimed book published a fortnight ago, ‘An Irish Atlantic Rainforest. A Personal Journey into the Magic of Rewilding’.

The farm in Bofickil was made up of 73 acres of largely forgotten land. But for Eoghan, it was a piece of heaven. Getting this for the price of a small house in Dublin felt like “a heist”.

“I’d never before laid eyes on anything like this wild, verdant and primeval landscape, and had no idea that such places existed anywhere in Europe, never mind Ireland,” he says.

He thought it belonged more in a tropical jungle than our own wind-blasted island. He felt like he was in the Mediterranean, with endless azure skies meeting wide-open sapphire seas.

Even the rain that used to get him down in Dublin didn’t bother him here, where there’s much, much more. “All the forms the weather takes just seem part of the natural rhythm and essences of the place.”

But although things looked good from afar, they were far from perfect up close. The land was in an awful state and the main culprits were goats and sika deer which roamed wild. It was, he admits, an ecological car crash.

What trees existed were being eaten to death, they had tops but you could see through them because there was no growth to block your view. The goats were “walking streamers – desert makers”. And so the first job to recreate his forest was to fence it off. And then the metamorphosis began.

“In the years after the deer fence went up, I was privileged to be witness to the most stunning, magical transformation of the land inside.” He soon realised what he was restoring wasn’t just native woodland, it was rainforest. Not tropical, as found in Latin America, but the far more rare temperate rainforest, which covers one-tenth the space across the globe. Later, after the death of his South Africa-born mother, he visits her homeland and finds forests there that shared many of the plants he had at home – they too were temperate forests.

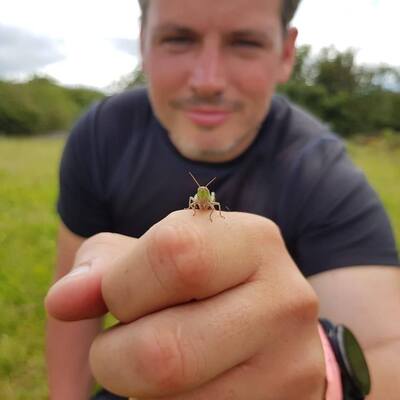

The defining species of rainforests are epiphytes: plants that grow on other plants – generally trees – without being rooted in the ground, living off moisture from the air. And they were everywhere in Eoghan’s forest.

His decade-long journey creating an Irish forest was a revelation. And he’s come out the other side with a stark message for an Ireland in the midst of what can be called ecocide, the destruction of a whole ecosystem. That message is: let nature grow.

And the best way to do that is just to do nothing, which is unfortunately one of the most difficult things to ask of any human. We love to control and manage. But Eoghan says the land is best determining its own state, rather than that state being dictated by us.

When you think about it in those terms, even planting trees is an admission that conservation has failed. Plants will naturally seed where in areas best to their liking: willow and alder in wetter places, oak in stony spots, rowan on higher ground. Not where we think they look best. Leaving nature to get on with it is the heart of rewilding.

And that doesn’t mean we can’t visit these forests – we just can’t take stuff out, Eoghan says. Resist the temptation to even tidy it.

“Nature has never needed, and generally still doesn’t need, human stewardship or management,” he writes.

All his trees are self-seeded, so were probably descendants of a genetic lineage in the area stretching back thousands of years. And they looked so different from the planted trees he had been familiar with.

“No two are alike in Bofickil,” he writes of his townland. “Straggly storm-battered oaks haven’t the characteristics people desire in trees. Those ones are tamed, cultivated, de-natured versions of their wild ancestors.”

It’s like comparing a poodle to a wolf. The Irish wolves, of course, have vanished, along with a host of other creatures, including many of the birds of prey that would have kept everything in sync. And we replaced them with farmland.

“Government proclaim their deep concern about the plight of nature, while maintaining policies that are actively destroying it,” he writes, pointing out that 6,000km of Irish hedgerow – the last refuge of nature – is ripped out every year.

Old, wild features with hundreds of species are being reduced to just two imports: a fast-growing grass and sheep. He calls it ecological amnesia -while we still consider the resulting countryside natural because we’re conditioned to think that’s how the countryside should appear.

“Despite the green image that is so carefully protected, Ireland is actually one of the most ecologically trashed and dysfunctional places on earth,” he says. It’s superficially green but in reality a sterile emptiness.

Even a good scheme like the national bee pollinator plan that allows grass verges to grow “is taking teaspoons to problems that are unfolding on the scale of tsunamis.”

Eoghan says that in Ireland “flat monocultural banality is the ideal always strived for. And there is practically unlimited mechanised power available with which to impose it. Everywhere, the ancient forms and features that tell the story of the land, and make it special and rich, have been – and are being – erased forever at a savage rate”.

And Dúlra certainly recognises what Eoghan says is the downside of being aware of this “great dying” – he too has a heightened consciousness of how we are still destroying what remains of nature. One expert wrote: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” So true.

Even the land around the outskirts of Belfast has taken an ecological battering in the last couple of years as hedgerows are pulled out and soggy fields turned into dead green pasture.

Eoghan says this knowledge “can bring a heavy and at times lonely anguish... even worse when you realise how hard it is to change and that so many people are oblivious to it.”

The rich habitat of Eoghan’s land once covered 80 per cent of Ireland. Today our forest cover is increasing, but instead of native trees, they’re battalions of imported spruces planted as investments. These terrible plantations account for 90 per cent of our ‘forest’ cover, while it represents just three per cent in Europe. And the contrast between natural forest and a plantation “really does have to be experienced at first hand to be fully appreciated. They are entirely different entities,” says Eoghan.

Inside Eoghan’s wild forest signs of past human life linger, however – abandoned stone buildings and signs that land was used to grow crops. He says it’s a post-apocalyptic landscape that’s been rewilded much like the land around Chernobyl was. Because Beara was once thronged with people before the Great Famine – its 1841 population was 39,000; today it’s just 6,000.

But even with fewer people, today we have the means to beat nature into submission. Eoghan says his 73-acre ecosystem is self-regulating. “Remember that all ecosystems – and their global sum, the biosphere – did that perfectly well for hundred of millions years before we came on the scene,” he says. The aim of rewilding is not to turn the ecological clock back in time, but to allow it to start ticking again. He hopes the plethora of missing Irish species, including birds of prey and eventually beavers and wolves, will be allowed to return as they are cogs that are missing from that ecological clock.

And he warns against trying to focus on the plight of a single species. Trying to save nature one piece at a time doesn’t make much sense, even if we had all the time in the world – which we certainly do not. It’s best to save the whole ecosystem. “Strange as it might seem, what birds, bats, bees and everything else really need isn’t boxes stuck on trees or fence posts, but actually wild habitat,” Eoghan says.

Eoghan hopes his Beara forest will act like a pebble thrown into a pool, rippling out awareness of Ireland’s lost rainforests that are lying dormant under our feet.

They just want to be allowed to grow.

• An Irish Atlantic Rainforest by Eoghan Daltun is published by Hachette and is available in all good bookshops and on Amazon.

• If you’ve seen or photographed anything interesting, or have any nature questions, you can text Dúlra on 07801 414804.