THIS Saturday, August 2, the 2020 National Hunger Strike Commemoration will take place online. Saturday will also be the anniversary of the death on hunger strike of Andersonstown man Kieran Doherty. The national commemoration for the ten H-Block hunger strikers, as well as for Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, who both died in English prisons, takes place each August. However, like so many other events this year Covid-19 has disrupted long established commemorations and organisers have had to go online.

I have watched all of the online events and participated in many of them. The organisers are to be commended for their efforts and their ingenuity. They have successfully combined music and song, poetry, news footage of the time, and interviews with friends and relatives to create informative, emotional and uplifting productions.

The online events for the hunger strikers have been especially poignant. The memories come flooding back. The Fermanagh South Tyrone by-election and the election of Bobby Sands. His death and funeral. The deaths that followed of Francie Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine. The general election in the South in June 1981 in which Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew were elected as the first TDs of this generation of republicans.

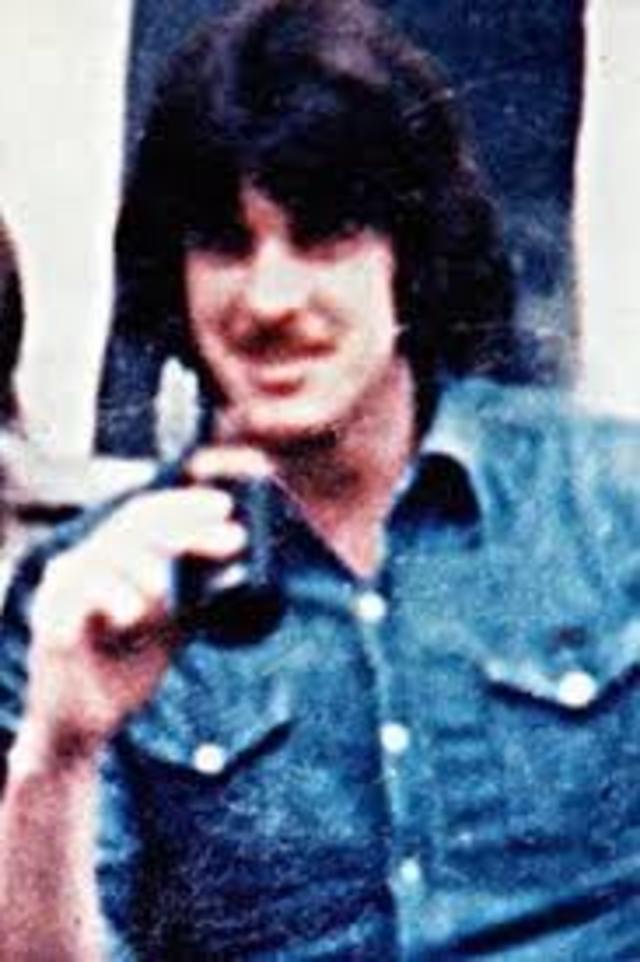

BIG DOC: Kieran Doherty TD who died on this day, August 2, in 1981

The marches, protests, the funerals, and the confrontations with British state forces. The attack on Joe McDonnell’s funeral, the plastic bullet deaths. All against the backdrop of a small number of courageous and amazing human beings taking on the criminalisation and demonisation policy of the Thatcher government.

Prison struggles have always been an important part of the story of Ireland’s long struggle for freedom and independence. From the 1798 Rebellion, to the Young Irelanders and Van Diemen’s Land in Australia, the Fenian prisoners, driven mad by horrendous conditions in English prisons in the 1880s, to the 1916 Rising and Kilmainham, and prisons and prison camps in Ireland, England and Wales. The blanket protest of the H-Blocks and Armagh women’s prison and the resulting 1981 hunger strike, were a watershed moment in this phase of our struggle and of modern Irish history.

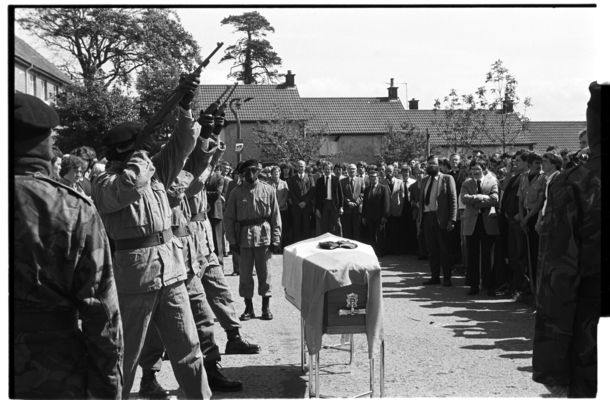

ANNIVERSARY: The family of Kieran Doherty at his graveside in Milltown Cemetery as he is laid to rest

Regrettably, there have always been those in the media and political establishment in Ireland who enthusiastically joined the chorus of condemnation of republicans by the British. It served their narrow self-interests. In particular, the use of abusive and sectarian language, of describing political opponents in terms that make them less than human, was used for generations by the Unionist government at Stormont to justify discrimination and repression against nationalists. It was also a fundamental part of the counter-insurgency strategy of successive British and Irish governments to defeat republicanism. British governments in colonial wars after 1945 demonised their opponents to defend the use of concentration camps in Kenya or torture and shoot-to-kill tactics in Oman, Malaya, Aden, Cyprus and Borneo or the creation of counter-gangs to facilitate collusion between state forces and state-sponsored terror groups.

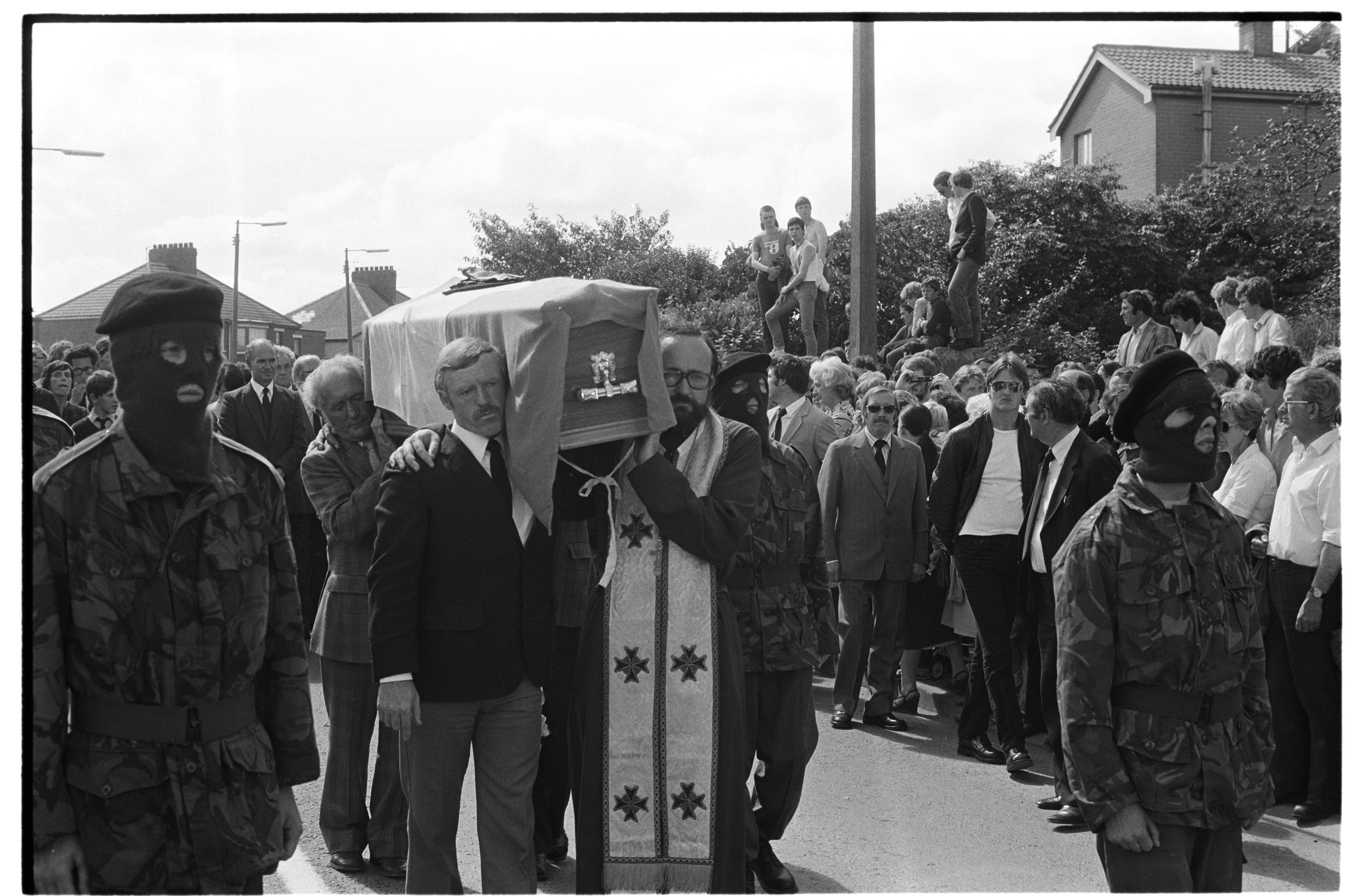

FINAL JOURNEY: Kieran's sisters Mairéad and Siobhán McKenna and sister-in-law Betty Doherty carrying his coffin on the way to Milltown Cemetery

The use of racist language to dehumanise people has been consciously used to excuse and justify slavery, the exploitation of native peoples, of women, and the ill-treatment and abuse of others. The English media of the 19th century regularly pictured the Irish as ape-like. One Punch satirist described the Irish who fled to England after the great hunger as “a creature manifestly between the gorilla and the negro” which sometimes “sallies forth in states of excitement and attacks civilised human beings that have provoked its fury”.

BRUTISH

For centuries the Irish were depicted as brutish, drunkards and stupid. The poverty and destitution, the forced emigration and cyclical famines were blamed on the Irish character, not British colonialism. The recent years of conflict saw British cartoonists and newspapers repeat this racism. In the 1980s one writer in a mainstream British newspaper described the Irish as “extremely violent, bloody minded, always fighting, drinking enormous amounts, getting roaring drunk” and said that IRA violence tended to make them “look rather like apes – though that’s rather hard luck on the apes”.

Even today there are some in the media, in academia and in the political establishments who believe it is still okay to use degrading and insulting language when describing Sinn Fein and our voters. A column last week in the Irish Times referred to the need to detoxify Sinn Fein, and of the party needing to be “house-trained”, is a recent example.

It’s at times like these that the heroism of the hunger strikers and the words and deeds of Bobby Sands, Kieran Doherty and their comrades, and of Mairead Farrell and hundreds of others, shine through.

So, on Saturday evening as you sit down to watch the 2020 National Hunger Strike Commemoration on Facebook, on YouTube and Twitter, remember the courage of Kieran Doherty and his comrades.

39 years ago at around 7.15pm on the evening of August 2, Big Doc died. He had been on hunger strike 73 days. He was just 25 years old. Kieran was first arrested as a 17-year-old and interned. He spent seven of the last ten years of his life in prison. Big Doc’s remains arrived at his family home at Commedagh Drive in Andersonstown in the early hours of the following morning. Two days later thousands followed his cortege to the Republican Plot in Milltown Cemetery where he was laid beside Bobby Sands and Joe McDonnell.

SHADOW OF HIMSELF

I knew Big Doc. The last time I met him was a few days before he died. I was visiting the prison hospital to speak to the hunger strikers. After speaking to Tom McElwee, Lorny McKeown, Matt Devlin and others I walked into Big Doc’s cell. He was too weak to join the others. I had known Big Doc on the outside but there in that prison cell he was a shadow of himself.

Doc was propped up on one elbow, his eyes unseeing. He looked massive in his gauntness, as his eyes, fierce in their quiet defiance, scanned my face. I spoke to him quietly and slowly. I sat on the side of the bed.

ÓMÓS: Monsignor Ó Ceallachain from Toronto helps shoulder Kieran Doherty's coffin.

I told him that he would soon be dead and that if he wanted I would leave the blocks and announce that the hunger strike was over. He paused momentarily, and said: “We haven’t got our five demands and that’s the only way I’m coming off. Too much suffered for too long, too many good men dead. Thatcher can’t break us. Lean ar aghaidh. I’m not a criminal.”

After that we talked quietly for a few minutes. As I left his cell we shook hands, an old internee’s handshake, firm and strong.

“Thanks for coming in”, he said, “I’m glad we had that wee yarn. Tell everyone, all the lads I was asking for them and…”

39th Anniversary of Hungerstriker Kieran Doherty TD. Cyclists send solidarity to Basque Political Prisoners with another 140km to 3,000,000km challenge #IsanBidea. #FreeThemAll @sortuEH withFormer Irish Olympic 1972 protestor and ex prisoner, Cyclist Brian Holmes, . @cllrconlon pic.twitter.com/m5M43YoOQN

— Caoimhín MGM (@caoimhinmgm) August 1, 2020

He continued to grip my hand. “Don’t worry, we’ll get our five demands. We’ll break Thatcher. Lean ar aghaidh... For too long our people have been broken. The Free Staters, the Church, the SDLP. We won’t be broken. We’ll get our five demands. If I’m dead, well, the others will have them... I don’t want to died but that’s up to the Brits. They think they can break us. Well they can’t. Tiocfaidh ár lá.”

Big Doc was right. Thatcher was beaten. The political prisoners won their five demands. And today because of their self-sacrifice and that of countless others, Sinn Féin is the biggest party on the island of Ireland. We refuse to allow anyone to delegitimise or criminalise the hunger strikers or our struggle. Kieran Doherty put in well in those final moments before we parted. “Lean ar aghaidh” – Go ahead.