DURING the years 1848 –1850 a pandemic of Asiatic cholera occurred on an international scale, originating in the Indian subcontinent. The Belfast Sanitary Report of November 1848 described Asiatic cholera as a “formidable disease, which, in the vastness of its sway, and fearful rapidity of its attack, is without a parallel.”

In Russia alone between 1847-1851 the cholera epidemic was catastrophic claiming over one million lives.

Ireland suffered approximately 30,000 cholera deaths during1848/49, when the Great Famine ravaging Ireland would claim the lives of over one million people. Belfast had the first recorded case of cholera in Ireland and also the first fatality. The outbreak in the town began in November 1848, extending with increasing severity to October 1849 when the epidemic had largely run its course. The final cholera report for the Belfast Union to 4th October 1849 stated, of 3,524 cholera cases 1,156 (33%) had died.

...one of the inmates was seized with sudden illness. The patient was affected with cramps and vomiting, and his hands and face were as blue as indigo... the other symptoms showed sufficiently clearly that the system was charged with cholera.”

The causes of cholera and its transmission were not entirely understood in the mid-19th century. It was initially thought of as ‘airborne’ – caused by transmission of poisonous vapours due to poor sanitation, the ‘deadly stench’, but it was in fact a ‘waterborne’ disease. Symptoms of cholera were severe dehydration and diarrhoea, vomiting, rapid heartbeat and fatigue. It had a high mortality rate but it also had a significant recovery for many patients. It was caused by bacterium – ‘vibrio cholerae’ which typically spread in poverty stricken over-crowded slum areas with poor sanitation, when human sewage was coming into contact with rivers and the lack of efficient sewage systems meant that drinking water from rivers became contaminated and the disease spread.

Cholera – First Reports

The first recorded case of cholera diagnosed in Ireland was in Belfast and was reported in the Banner of Ulster, November 3rd, 1848. At a meeting of the Belfast General Hospital Committee of 2nd November, Dr S. S. Thompson disclosed that a male patient had been diagnosed with Asiatic cholera the day before (1st November) at the Belfast Lunatic Asylum (Falls Road).

“...one of the inmates was seized with sudden illness. The patient was affected with cramps and vomiting, and his hands and face were as blue as indigo... the other symptoms showed sufficiently clearly that the system was charged with cholera.” He was subsequently believed to have survived his illness. Dr Thompson added, “The Lunatic Asylum was not the place where they would have expected it to occur, but... thought it desirable, without wishing to cause unnecessary alarm, to make it known to the meeting.”

The second reported case was in the ‘Belfast Union Workhouse’ and was reported in the ‘Banner’ on 12th December 1848. This was an Irish pauper named Tiernan who arrived in Belfast from Glasgow. Before arrival he had been living in a house in Edinburgh where two cases of cholera had occurred. At his request the authorities transferred him to Belfast. He was admitted into the Union Workhouse Fever Hospital on December 2nd, where he died of cholera on December 4th. This was believed to be the’ first cholera fatality’ in Ireland at the onset of the 1848/49 epidemic.

The same edition reported a second fatal case at the workhouse when a female pauper aged about 34 died of cholera on 11th December. This was followed by a report in the Northern Whig on Tuesday 19th December 1848 of four cases of cholera among the children in the workhouse on16th and 17th December, when sadly all four children died.

Barrack Street from Durham St, 1913, Courtesy The Deputy Keeper of the Records Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, LA/7/8/HF/3/81

Preparations

Anticipating the ‘invasion of Asiatic cholera’ like that of 1832, the authorities moved swiftly to coordinate ‘preventative measures’ through public awareness campaigns to emphasize personal cleanliness and hygiene, improving public sanitation and expanding medical provision and facilities.

By mid-January 1849 the Belfast Board of Guardians had advanced it plans to acquire additional accommodation to house paupers, if necessary. They had agreed with Messrs Mullholland, the proprietors of Francis Street Mill, for its temporary use as supplementary wards; accommodating up to 800 persons in the event of workhouse overcrowding. Plans were also made with the trustees of the Magdalene Asylum (Donegall Pass) for the use if needed, of unoccupied premises at the rear of the church.

Arrangements were agreed between the Poor Law Guardians and the General Hospital Committee for additional medical support for the treatment of cholera patients. These arrangements were acted on by the 19th January and the old cholera hospital, behind the main hospital buildings in Frederick Street was again put in requisition and fitted out with all necessary refurbishment and equipment. The six medical dispensaries were staffed by medical attendants 24/7 to deal with cholera cases and fully prepared to meet the outbreak. The Belfast General Dispensary was praised by the Northern Whig for “the facilities that its excellent arrangements are now affording for the treatment of cholera.”

“In the family of James Ashwood there is a fearful instance of the apathy and carelessness of the poor, with regard to infection...This man’s child, five years of age, was applied to her father as a heater, while labouring under cholera— the child was attacked by the disease, and both were sent to hospital—both have since died.

Likewise the Belfast Sanitary Committee was proactive in carrying out inspections of housing, alleys, lanes and courts making recommendations for sanitary improvements and cleansing, whitewashing, drainage, serving notices for removal of nuisances such as cess-pools containing raw sewage and dung heaps across the town. In December 1848, on recommendations by the health officers, 195 poor houses were cleansed and whitewashed, 266 wretched families were supplied with dry fresh straw bedding, and 27 nuisances removed.

Advance of the Cholera Epidemic

The General Dispensary report for week ending 15th January showed cholera cases were rapidly increasing and had occurred in the following localities: Tea Lane, Maxwell’s Court and Williams Place, off Sandy Row, Fleet Street, off York Street, Lewis’s Court and Cahoon’s Court, off Brown Square, Charles Street, off Union Street, Stephen Street, off Little Donegal Street. The Banner of Ulster of January 30th 1849 reported the total cases of cholera in Belfast Union area at 208, with 83 deaths and illustrated the impact of cholera on one family,

“In the family of James Ashwood there is a fearful instance of the apathy and carelessness of the poor, with regard to infection...This man’s child, five years of age, was applied to her father as a heater, while labouring under cholera— the child was attacked by the disease, and both were sent to hospital—both have since died. Then there remained Ashwood’s wife and her two remaining children... they were reported at the dispensary ill of cholera and immediately visited. The youngest child, two years old, died before the medical attendant left the house and the poor mother was sent to the hospital without delay where she remains, with very little hope of recovery. The remaining child, not ill, was taken into the house of a neighbour, an inmate of which has since been attacked by the disease.”

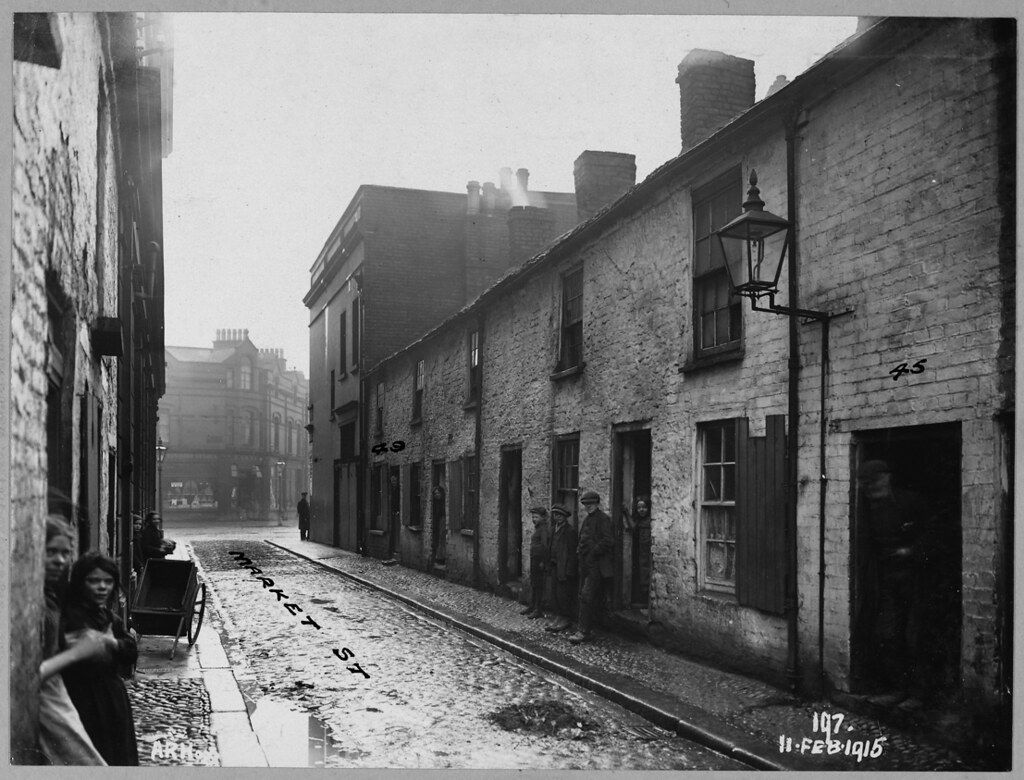

Market St, Cromac District 1915, Courtesy The Deputy Keeper of the Records Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, LA/7/8/HF/4/197

Meanwhile the situation continued to deteriorate; by the19th February total cases of cholera since commencement in the Belfast Union were 515, died 179, discharged 222, remaining 114. The Northern Whig later published a letter from Dr S. Browne of the Belfast Sanitary Committee, expressing his frustration and dismay at the lack of compliance with its guidance from among the poor and the landlords.

“Unhappily, there seems to have been a considerable amount of incredulity in the public mind and sanitary reformers were regarded as mere visionaries. Not only have the occupants of those places, which it was told would suffer most, turned a deaf ear to remonstrance and advice... but the proprietors of these localities have either by direct or negative resistance, very much retarded the benefits which it was hoped would accrue from the sanitary movement of the bygone year...

“Take for instance, Lennon’s Court, off Smithfield. There the disease had spread most rapidly and with great fatality. And what are the circumstances of that court? It is a cul de sac, narrow and confined. Without ventilation, or back outlet out to the houses—the surface saturated with excrementious matter and reeking with effluvia only to be borne by persons habituated by them. Shall we wonder, then, if the wretched in habitants of the horrid den were decimated, nay, entirely cut off, by the epidemic invasion?”

The Town Council meeting on 1st February (reported in the ‘Banner’ on the 2nd), discussed a major problem exacerbating the cholera epidemic – the forced repatriation of large numbers of Irish paupers from Scotland to Belfast. During the late 1840s Irish paupers were subjected to compelled repatriation to their place of origin in Ireland and it was the responsibility of the Poor Law Union of their home destination to provide support for them. Scotland however deported them to the ‘nearest port’ which was normally Belfast, even if they belonged to counties in Connaught or Munster or elsewhere.

“Though it has been severely felt... we will hope that its existence has not been without its use... that it has been the means... of teaching the masses the intimate connection between disease and imperfect sanitary regulations

This placed enormous pressures on Belfast’s charitable organizations and medical facilities to provide care and support for them, including many paupers who were suffering from disease including fever and cholera. The Council was concerned at the financial pressures of supporting their own poor with food and medical care without having this additional burden; revealing that from December 1st 1848 to end of January1849 907 paupers had arrived in Belfast from Scotland. It was stated, “The consequence must be, if a bold step be not taken, that the town will suffer severely.”

The Belfast Newsletter was enraged at the practice of the Scottish authorities. The notoriously anti-Irish ‘Times’ newspaper in London mocked Belfast authorities for their objections to repatriation. On 30th March the Newsletter paraphrased the Times, ‘Glasgow alone, it is said, has paid more than £75,000 this last year, for the relief of Irish vagrants, illegally forced on its parochial institutions’ and ‘to make the matter still worse, Belfast, the metropolis of Ulster, has itself taken the lead in the unnatural work of pauper deportation, shipping off its own perishing poor, and casting them by thousands on the bare quays of Glasgow.”

The Newsletter took grave exception to this, condemning it for its “malignity, fraud and falsehood”.

Meanwhile reports continued throughout the first half of 1849 of localities in Belfast hardest hit as cholera spread and cases and mortality rates increased. By 23rd April the total diagnosed cases was 1,555 of which 454 had died. The Belfast Sanitary Committee of 1st October referred to areas most affected with cholera – Sandy Row, Pound Street, Lettuce Hill, Falls Road, Ritchie’s Place, Millfield, Charlotte Street, Little Howard Street and Green Street. The Cromac and Durham Street areas adjacent to the Blackstaff and Pound Burn rivers were particularly badly hit where “the cholera told fearfully”.

Inevitably the cholera epidemic would run its course; officially announced at an end on October 12th 1849 by the Belfast Board of Guardians. Of 3,524 cholera cases 1,156 had perished. The authorities believed their measures had succeeded in reducing the spread of the disease and prevented a much higher death toll. Other locations in Ireland such as Dublin and Cork had significantly higher mortality levels.

The lessons for the advancement of sanitary reform in Ireland were not lost sight of.

The Sanitary Committee on 1st October was addressed by Dr A Malcolm, who reflecting on the epidemic and its outcomes stated:

“Though it has been severely felt... we will hope that its existence has not been without its use... that it has been the means... of teaching the masses the intimate connection between disease and imperfect sanitary regulations — and that, if it should please the great Disposer of Events to let loose its power upon us, at a future period, its lessons now will have brought us to appreciate and realise in this locality, the saving principles of sanitary reform.”

Brendan Muldoon ©2021