A new book that sheds a light on the life of a 19th century Irishman’s exciting — and even fantastical — experiences on the American frontier will be launched at An Chultúrlann this Saturday at 1pm.

The bilingual, semi-autobiographical account of the life Eoin Ua Cathail will, for the first time, include English translations of his tales of derring-do in the Indian Wars and as a bear-slaying logger.

Born in Templeglantine, County Limerick in 1840, Ua Cathail emigrated to the United States in 1863 at the height of the Civil War.

After a stint in the US Military and three years as a police-officer in Chicago, Ua Cathail moved to Pentwater, Michigan, where, as a woodsman, he witnessed the impressive and shocking expansion of US capitalism first-hand.

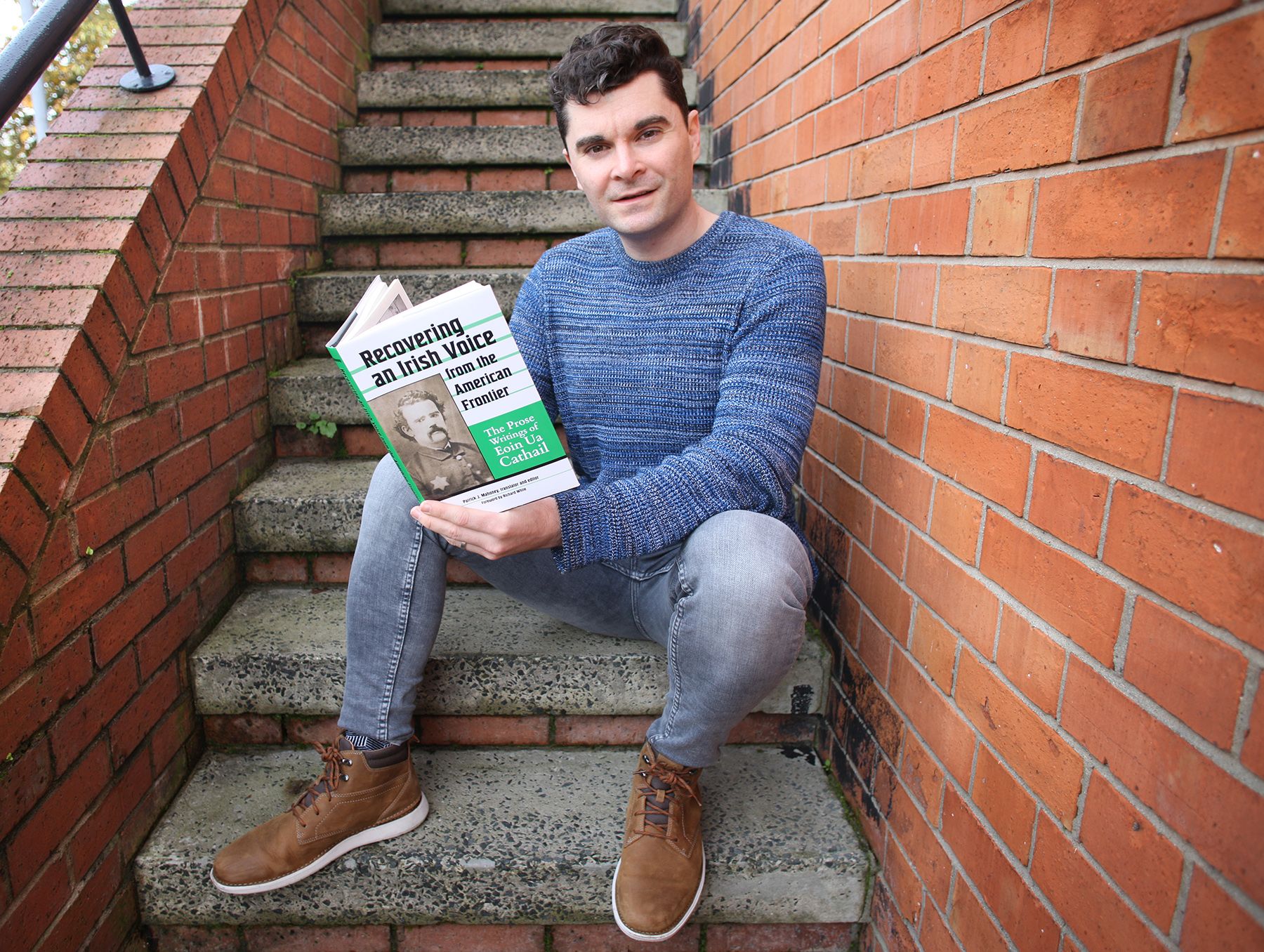

Recovering an Irish Voice from the American Frontier: The Prose Writings of Eoin Ua Cathail, has been written by Galway University alumnus, Patrick Mahony — who himself first learnt Irish from a former blanketman on a Connecticut building site.

As well as containing three private letters and a dictionary written by Ua Cathail, the book is largely comprised of 14 semi-autobiographical stories that marry the Irish language with the 'dime novel' fiction of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In that fashion, Ua Cathail’s stories offer an exaggerated, but undeniably exhilarating, look at life on the American frontier.

“It’s just fascinating because there are (stories about) native Americans and fighting along the plains, and then there were these stories about working in the woods in Michigan as the country is expanding across the continent, and he’s talking about the effects of hyper-capitalism and deforestation at the turn of the 20th Century,” Mahony said.

“So in a lot of ways he’s kind of ahead of his time. Once I saw that all that stuff was there I figured I had to get these stories out to the public and bring them to a wider audience.”

As well as boasting their own literary merit, Ua Cathail’s writings are a rare example of Irish language literature penned outside of Ireland in the 19th and early 20th century.

“Even though there are a million Irish speakers who emigrated around the time of the Famine, not a lot of them left accounts of their lives in Irish,” Mahony explained.

“I learned my Irish in America as well. Eoin Ua Cathail was from a Breac-Ghaeltacht - or broken Gaeltacht - in west Limerick, and in one of his letters he actually writes about learning his Irish in the US – even though he would’ve had some Irish as a kid.

“He gives this account of who the other Irish immigrants were who would’ve spoken Irish with him and taught him things in Irish, even to read and write. I had some sense of solidarity with Ua Cathail in that regard. It’s fascinating the way he put language together, and it’s more extraordinary that he even managed to write these stories exclusively in Irish.”

Despite being a “fascinating figure”, Ua Cathail is also a controversial one who espouses much of the settler-colonial views typical of America at that time. This includes many negative attitudes towards Native Americans - who are the subject of several violent encounters – as well as a general support for the aims of a nascent US imperialism.

Adds Mahony: “I think he offers a window into debates that are going on at the moment - and I suppose that are always going on in Irish society - around the relationship of Ireland to imperialism. That’s currently being fleshed out in academic and popular discourse.

“Eoin Ua Cathail is fascinating because he’s an Irish speaker, he’s a Gaelic Leaguer, he’s very much a nationalist, but then at the same time when he speaks of American imperialism he’s almost a champion of that. He’s very enthusiastic about the Spanish-American War, and even on the subjugation of Native Americans, which he touches on, he doesn’t have a large amount of sympathy for them.”

Mahony also pointed to the connection to be found between US expansion and the Fenian movement.

“Wherever US expansion went there was a Fenian circle of soldiers,” he said.

“Although they’re expressing anti-colonial views in terms of the Irish situation and even far flown – they talk about the Maori, the Cubans and the Greeks – but they have no sympathy for the Native Americans who they’re in close contact with. It's kind of a case of ‘the grass is greener’ when it’s far away.

“I think Ua Cathail’s views probably area reflection of his own experience but also the wider culture in the U.S. at that time.”

Mahony does not attempt to skirt the controversial aspects of Ua Cathail’s writing.

“I try to contextualise it historically and show him as a man of his time and show where he fitted into a wider American culture of settler-colonialism and where he was problematic,” he stated.

“People are complex, so there are things you can admire about them and things you don’t admire,” he said.

“What’s interesting about his stories as well is that when he’s talking about his time on the plain that’s where you see the stories about massacres of Native Americans, but when he’s talking about his time in the forests in the Midwest, he has Native Americans who are his friends and hunting partners.”

During his own lifetime, Ua Cathail began corresponding with Conradh na Gaeilge founder, Douglas Hyde, who attempted, without success, to have his writings published.

“He sent them back to Ireland to Douglas Hyde to be published, and that was the kind of literature that was popular at the time, and it was popular even in Ireland at the time – these kinds of settler-colonial narratives.

“If you look through the newspapers of the early 20th century in Ireland there are loads of stories saying things like "I was friends with Buffalo Bill Cody and we got attacked by native Americans" – all these kinds of fanciful stories are filling the columns of newspapers.

“Ua Cathail probably thought he could make a buck off writing these stories in Irish.”

Recovering an Irish Voice from the American Frontier: The Prose Writings of Eoin Ua Cathail will be launched at An Chultúrlann on 27 November.

The book, published by University of North Texas Press, is available online here.