“…barbarous abodes, ill ventilated, ill drained, old, rotten, and unrepaired; parcelled off in rooms, the windows patched with rags and paper, and yet excessive in the rent. In some of these houses sixteen or seventeen human beings are huddled together in one flat, the clothing insufficient, the air inside impure from the overcrowding of the inmates.”

This horror was the description of the landlord’s dwellings in Smithfield presented in a report to the Belfast Board of Guardians in April 1865, recommending a new urban plan for the entire area. “…first, that it appears to be, if possible, worse than any other in town, in all that tends to produce social and physical wretchedness; that it’s exceedingly central and that here a possibility of applying a remedy seems to exist.”

Reflecting public concern, the News Letter of April 13, 1865 wrote: “It is wholly impossible that a locality such as that which exists between Hercules Street and Smithfield can be allowed to remain in a condition of filth, without sewage, without water, without wholesome air, almost without the light of heaven, and that the public health will not in some measure suffer...”

With Belfast’s dramatic population growth – 122,000 in 1861 to 200,000 in 1876 –pressure for housing and sanitary reform became acute. Three vital pieces of legislation were passed for Ireland, providing the Town Council with new powers to address the problems. The Public Health Act 1866 compelled local authorities to improve sanitary conditions and remove nuisances to public health, while overcrowded residences became illegal. The Artisan and Labourers’ Dwelling Act 1875 gave local authorities powers to demolish slum houses and replace them with improved and healthy housing and the Public Health (Ireland) Act 1878 provided additional powers to address public health and hygiene, clean water supplies, and infectious diseases control.

Not surprisingly the Town Improvement Committee using the powers under the 1875 Act, recommended a first phase with the clearance of part of Smithfield’s dwellings – Hudson’s Entry, Ritchie’s Place, Smithfield Court, Smithfield Place and Hudson’s Court. These entries and courts, like so much of the housing stock in Smithfield, were simply unfit for human habitation. It was agreed that the affected population of 387 inhabitants should be accommodated in new dwellings to be built on new ground adjacent to Ross Street in the Falls Road area. The Town Council approved the plan on November 1, 1876, at a cost of £10,000. The plan included the construction of a new street from North Street to Smithfield Square to improve access for the public and residents – Gresham Street (1879). Later, Hercules Street was replaced with the widened and transformed Royal Avenue (1881).

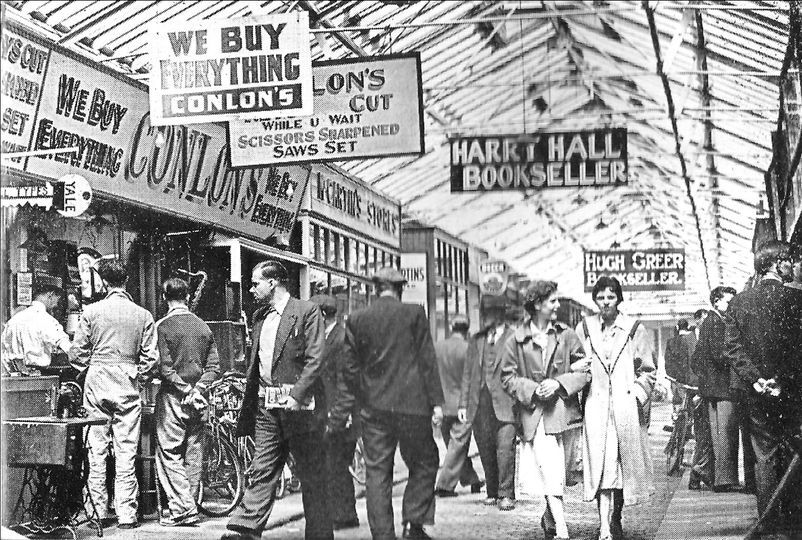

Smithfield Market 1905, W. J Mc Coy &Sons Antiques. Courtesy of NI Historical Photographical Society. National Museum NI.

Earlier, the 1848 Town Improvement Act ensured the transfer of the old livestock market from Smithfield to a new site named the Belfast Cattle Market. Smithfield Market would transform into the famous and much-loved general indoor market that defined the district for 150 years until its terrible destruction in 1974.

As the Council was grappling with the social and public health issues of Smithfield, the last quarter of the 19th century saw the iconic market grow in popularity, attracting the public in large numbers, drawn to its stores, stalls, nooks and crannies and the many wares and curiosities to be found there. By the early 20th century, its enduring appeal, convivial atmosphere and changeless-ness over time was eulogised in Herbert Moore Pim’s book, ‘Immortal Souls’ (1917), honouring the ‘Soul of Smithfield’. “In this city of commercial success there is something that has remained successful. We have a treasure in our midst, which, in the battle of bricks, lies unprotected, and ready to be ruined. Though built like a gridiron, it is no relic of municipal torturer’s activity…But it has come to us from the past, delicate and full of dust.”

Various memorable characters were associated with the market’s history. In the early 19th century, there was the well-known open-air auctioneer of his day at the cattle market, Jack Jeffer, with his incredible booming voice. In the late 19th century, there was the popular Dan Halliday, a delph trader who attracted customers by entertaining crowds outside his shop, spinning plates in the air, skilfully catching them just as they appeared ready to fall and break into pieces.

Then came ‘Jane the Nailer’, a trader who sang ballads at the market and another eccentric character, a down and out, who apparently lived his life, like Diogenes, in a huge wooden barrel close-by the market. Diogenes (412-323 BC), was a Greek philosopher who made a virtue of poverty and slept in a huge ceramic jar in the market-place of Athens. A Smithfield trader said of the man in 1940: “I remember him well. During the Boer War (1899-1902) they used to joke about him joining the army. Smithfield was a great place for recruiting sergeants in those days. Many’s the Ulster lad took the King’s shilling here, for as long as I mind it had an attraction for young people.”

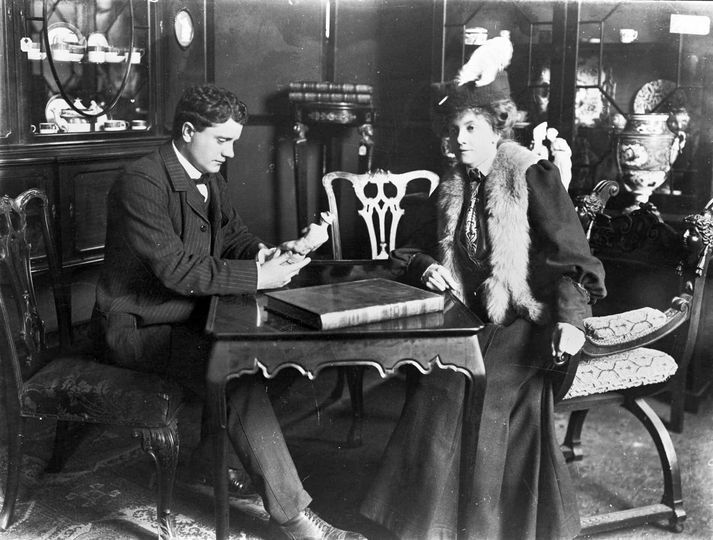

In 1917, Moore Pim described another ‘character’ of that time – Smithfield’s well-known ‘soiled clothes auctioneer’ who had “a large nose on a rather small face and always wore an exceedingly tall silk hat”, “...a glorious goblin like some undertaker shrouding souls as well as corpses, who emerges from licensed caverns and spreads out before him a splendid spoil... And before him he gathers garments of questionable quality, soiled and exquisitely splattered, while round him there rise glorious gnomes*, who presently seize upon such things as they desire...”

(*Traders at the auction with soiled clothes stalls at Smithfield.)

Smithfield Market old clothes trader, 1937. North and West Belfast Historical Photographical Society

The buying and selling pursuits that generated the market’s renowned vibrancy and vitality, gleaned from street directories and newspaper advertising, reveals the changing tastes of the public, with the popularity in book, furniture, hardware sales, later electrical goods and vinyl records, and not least the enduring popularity of children’s books, comics and magazines. But they also reveal the face of Smithfield evolving from the most densely populated district in Belfast to a concentrated trading centre of countless shops, small businesses, public houses and entertainments, with Smithfield Market as its beating heart.

The 1870 directory shows furniture specialists numbering 10 and tinsmiths 7, as the main dealers. One book dealer is listed, some clothes dealers, general-dealers and a few specialist traders repairing and creating new wares: coopers, carpenters, shoemakers, a basket-maker. By 1900, furniture dealers numbering 29’and hardware dealers, 15, were the dominant traders, although it’s likely some or even many of the same traders occupied several premises or stalls. By 1920 the range of traders and goods had vastly expanded: furniture dealers, booksellers, locksmiths, hardware and leather goods, antiques, delph, paintings, bicycles, toys/fancy goods, clothiers and with new technology radios and gramophones; one versatile trader, John Shearer, dealt in jewellery, binoculars and electrical goods.

Familiar trading names also began to appear, including Havlin’s hardware and key-cutters, Harry Hall bookseller (later the subject of a painting by renowned Belfast painter William Conor) and Greers, book dealers. Booksellers and furniture dealers now dominated the market and by 1932 booksellers were the leading single item dealers, located at 15 premises, most owned by the Greer family.

Moore Pim wrote warmly of the traders, bicycle dealers and the typically bizarre assortment of wares and bric-a-brac found there at that period. “One there is in Smithfield who gathers about him... crutches and corset-busts, turbines and teapots, sewing machines and Salvation Army tambourines, weighbridges and whetstones, yard-rules, and Yule-logs, zithers and Zulu shields. And beside him are strange old men who stew before stoves, and draw about them tyres and tubes.”

Historically Smithfield’s association with theatre went back to the late 18th century. Cathal O’Byrne in ‘As I Roved Out’ (1946) wrote: “In later times McCormick’s Theatre – where Little Nell died every night to the slow music of a slow drum and one fiddle – enjoyed an enormous popularity.”

Two small theatres were located in Smithfield Square in the 1850s: the Hibernian and the National Theatre, where some of the best actors of the day were said to have performed, the district said to be a centre for the stage in that decade. This image, however, is somewhat difficult to reconcile with the harsh social realities detailed in numerous contemporary accounts, including the Reverend WM O’Hanlon’s famous journal ‘Walks Among the Poor of Belfast 1852/53’ which described Smithfield as “a sort of tumour, a morbid ganglion in the heart of our city.” A district saturated with “drunkeries” and social degeneration.

Smithfield Market, 1950s, Courtesy of NI Historical Photographical Society

Nevertheless, Moore Pim, writing much later in 1917, immortalised the theatres’ importance to the historical fabric of Smithfield market. “...players were drawn to its doors, and actors of note strutted and smiled. And though the theatres are no more, the actors who should have long since died, remain like moths upon some ancient web, living while it lives.”

In 1913, the new era of entertainment saw the Central Picture Theatre opened in Garfield Street. It had one screen, 600 seats and was recalled as being cold, dark and uncomfortable. It later achieved a coup when it presented ‘Dracula’ starring Bela Lugosi in 1932. None of the larger cinemas showed the film, which became a huge hit for the cinema.

Jack Loudon of the Ballymena Weekly Telegraph wrote in August 1940 how, despite the wars years, Smithfield market retained its timeless atmosphere and character,

“You can buy black-out paper, ARP equipment, an up-to-date radio set or the most modern piece of domestic hardware there today. But turn around the next corner to where the women sit before the old clothes stands and you might well be in the Belfast of a hundred years ago.”

There was no shortage of gramophone records, but a real shortage of musical instruments: mouth organs, French fiddles and mandolins, which were mainly made in Europe. The book dealers were trading well, some of their best customers were soldiers stationed in Belfast in search of light reading, second-hand books or even rare editions. The traders conveyed to Loudon how strong the attraction Smithfield had stayed for children and remained so during the war years. “Generations of schoolboys have ‘raised the wind’ there by selling their old books and youthful collectors still haunt its stands in search of bargains.”

During the 1950s, ’60s early ’70s the vast array of wares continued to feature and sell at Smithfield’s stalls and shops. The market traders began to spread out around the square, occupying premises in the adjacent streets and lanes, such as Marcus Musical Instruments, Harry Hall’s Books, Kavanaghs, ‘I Buy Anything’, Rod ’n’ Wheel and street vendors’ fresh fruit and veg stalls. The 1960s were a particularly vibrant and exciting decade around the market when teenagers searched out the latest pop music and listened to the sounds piped out from such as Mary Byrne’s or Mrs Moore’s record shops.

Smithfield in ruins after the fire, May 1974. Picture, Kenneth Mc Nally, UTV

Gresham Street, well known for its book and record shops, bicycles and jewellery stores, had Cecil Creighton’s famous pet shop, originally founded in 1884, and Montgomery’s Pet Stores as its visual centrepiece and attraction, providing for the public the ‘gateway’ to Smithfield.

The popularity of bookstores like Harry Hall’s or Greers, and sales of children’s literature – books, magazines, comics and annuals – was another facet of Smithfield market’s allure across these decades. Numerous new and second-hand book stores and stalls were found there for excited and curious children to eagerly browse through. The Eagle, Dandy, Beano, Bunty and Mandy were standards and the enduring popularity of Enid Blyton’s adventures, the Famous Five, Mallory Towers, the Nancy Drew mysteries, and countless others. DC and Marvel comics featuring the famous superheroes like Superman, Batman or Spider-Man were highly popular and so for a period were the American horror comics – Creepy, Astounding, Tales from the Crypt and others – before eventually being withdrawn.

The tradition of Smithfield characters certainly remained, not least with Joseph Kavanagh. whose shop sign brazenly announced the claim, ‘I Buy Anything’. He brought a court action in 1954 against another trader, Peter Maginn, who decided to use the title ‘I Buy Anything’ above his own premises adjacent to Kavanagh’s shop. Kavanagh claimed the wording was associated in the public mind with his business for over 16 years, so much so that he even received post simply addressed to, ‘I Buy Anything, Belfast.’ Maginn’s action, he insisted, would mislead the public and affect his business. In January 1955, the High Court found that Kavanagh had “gained an interest” in the words for his business over time, entitling him to prevent any other person from using them in business there. Maginn was ordered to desist from using it.

During the 1950s Kavanagh, seeking maximum dramatic publicity, hired an airplane and pilot to fly low across the skies of Belfast trailing a huge banner through the air proclaiming ‘I BUY ANYTHING!’ Interestingly, Conlon’s general dealers in Smithfield market during the late 1950s and ’60s subsequently used the trade line with their shop name, Conlon’s, ‘We Buy Everything.’

Tragically Smithfield market was destroyed by incendiaries on May 7, 1974. The traders and the wider public were devastated. Onlookers at the scene openly wept. 200 tenants and staff of the 90 stores there lost their livelihoods. Joseph Kavanagh aptly described the old Smithfield market as having been “a living museum” in the city. The old market with its history, atmosphere and character was an irreplaceable cultural icon. A Belfast newspaper captured the psychological impact of its loss: ‘The Heart of Belfast Has Gone.’

Moore Pim, reflecting on the allurement, mystery and charm of the old market in the early 20th century, wrote: “Smithfield has its sentinels and skirmishers; it has its gates and its guard; it is as a walled city whose battlements are reared to heaven so that its virtue may remain inviolate. And to this day the curfew chimes the closing of its gates and the extinction of its fires; and then, dark and full of slumbers, it spreads out beneath the Ulster skies.”