BOMBING RUN: A seventies Cortina

A DISCUSSION on Twitter this week about the respective city centre locations of hamburger joints Wimpy and Lord Hamill’s caught Squinter’s attention because back in the 80s Squinter used to get his bus outside Lord Hamill’s (which was in Wellington Place, to answer the question – Wimpy was in Royal Avenue).

Early one evening around 1982 Squinter was standing at the bus stop with a few other commuters when a yellow Cortina with a black vinyl roof pulled up. The back kerbside passenger door opened and a bloke stepped out. He was wearing a parka with the hood pulled up and a big pair of Deirdre Barlow glasses. But what really caught the attention was the Castrol oil can with a bomb taped to it that he had in his arms.

Squinter was more intrigued than frightened, truth to tell. Rather than leg it, he watched – along with the other commuters – as the man walked up to the window of the shop next to Lord Hamill’s – Parson & Parsons tailors. He raised the device and hung it on to the wire security grill with a butcher’s hook and then walked back to the door of the car, which he’d left open. Just before he got in he turned to us and said, calmly and without shouting, “That’s a bomb.”

Again, nobody shrieked and fled, rather we all stood and watched as if this was a movie. The back door closed and the car pulled out to enter the traffic stream, at which point Squinter noticed that a UDR Land Rover had stopped and was letting the Cortina out. Still Squinter was oddly detached from the scene, although in retrospect the possibility of chaos erupting and bullets flying was extremely high.

Out pulled the Cortina, unhurriedly, and Squinter couldn’t see whether the IRA driver gave the UDR driver a cheery wave of thanks. The car travelled a few yards before taking a right into Upper Queen Street while the Land Rover continued in a straight line towards City Hall.

Squinter can’t remember what month of the year it was so he’s not sure how bright it was, and while he’s fairly sure it wasn’t night, it could well have been dusk. Whatever the conditions, Squinter had to shake his head at what he’d just seen – a British army mobile patrol coming across a bomb attack and noticing nothing. And it occurred to Squinter that the driver of the Cortina must have been doing a lot more than shaking his head when he looked out and saw Geordie waving him out. Squinter stood around for a while trying to process what had just happened and at some unspecified time the RUC and British army started to appear on the scene, at which point Squinter decided that the best thing to do was to dander round to Castle Street and get a black hack home.

Twenty minutes later Squinter was sitting in the back of the taxi at a roadblock at Divis Tower, the driver being quizzed by a British soldier, another British soldier bending to take a good look at everyone in the back. And then the bomb went off and for a firebomb it made a heck of boom. The soldier staring at us in the back stood upright and said, “What the f**k was that?”

Squinter decided that, all things considered, it was probably best not to tell him.

Cheer up everybody, for goodness' sake. In under three weeks the days start getting shorter.

— Squinter (@squinteratn) June 2, 2020

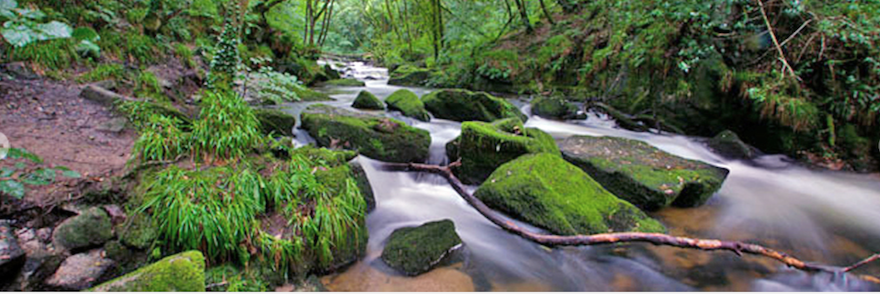

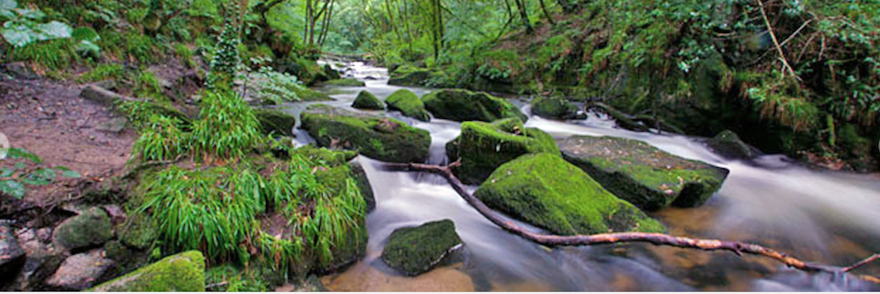

A COLIN GLEN CLIFFHANGER

TO Colin Glen upper with the dog early on Sunday evening for the daily Covid constitutional. Along the shaded path we go, shafts of sunlight dappling the way, stopping to admire the butterflies dancing from one forest bloom to the next. The air is thick and heavy with Squinter’s favourite smell – wild garlic.

A camera clicks in Squinter’s head and there’s a vivid snapshot of the past: Squinter at 12 years of age with a group of mates noisily proceeding along this very route. The boy stops to pick wild garlic, pulling apart the waxy leaf and rubbing his fingertips on the torn part to cover them with the distinctive odour. Squinter used to do that so he could still smell it on the way home and he stops and does it now, as he always does.

DOWN THE GLEN: Cliff challenge

The bird choir’s volume increases with every passing minute as the singers start to think about roosting and Squinter occasionally lays down his stick and puts his binoculars to his eyes, but finding a bird is tricky in the lush green canopy overhead.

Presently he’s brought to a halt by the Colin River. The old wooden bridge has gone, the only reminder that it was ever here the still sturdy supports on the bank. To the left is the mini-cliff which gave Squinter his fear of heights. Or perhaps that should be deepened his fear of heights (or heightened his fear of heights) because that was a pre-existing phobia that had just never been tested to this extent.

First time we arrived at this spot Squinter wasn’t unduly worried. One or two of his friends stepped across the stones and began messing about at the bottom, but the rest of us remained on the bank, looking for spears. Yip, spears. We were rarely to be seen in the great outdoors without a slender, four-foot branch sharpened and hardened by fire at the tip. And when we weren’t carrying them we were on the look-out for them.

But gradually the numbers on Squinter’s side of the river dwindled as more showed an interest in the small group now about 30 feet up the cliff and determined to make the summit. It was at this point that Squinter got worried because the newcomers had also joined in the ascent and the mass excitement was growing, with shouts and laughter echoing off the rugged cliff wall.

Before long, Squinter stood alone at the bottom, a few of his friends having made the summit, the others in various stages of ascent. Heart pounding, he considered his two options: 1) skirt the cliff and take the path leading up to the top; 2) suck up the fear and climb it. And anyone who ever knocked about in a sizeable group of children knows that the first option was never a goer, the shame and humiliation would have been too much to bear. So up Squinter went, following the kid just above him, searching for handholds and footholds which appeared to have the lowest degree of difficulty. The higher he got the more regular became the waves of terror surging along the back of his legs up his spine. His heart was threatening to burst out of his chest, such was the work being required of it and he had no idea whether that roaring sound was blood pumping in his ears or the river below. All the while he imagined what the sensation of falling would be like when it inevitably came, and he wondered whether landing on the river boulders below would kill him straight away or whether he’d be left a mangled mess. Then the breathing started to go, fading away to short, jerky gulps that seemed to come from the base of his throat rather than his lungs. And the more he wondered why these things were happening to his body, the more adrenaline coursed through him and wrought its physiological havoc.

After a while, the stones and the dirt showered on his head from the boys above him stopped and Squinter knew he was the last one on the cliff face. He had to rely on this clue alone because at no time until the final five feet did he look up, concentrating his attention on the single next move alone.

Then the straight line of the cliff began to curve just a little towards the top, but when Squinter realised this was the final stretch, he realised both how high up he was and how sickeningly tragic it would be if he were to fail so close to the goal.

And suddenly Squinter was finding handfuls of vegetation and soil instead of rock. Relief flooded over him, but only until he realised that he had no longer anything to pull himself up by. After what seemed like a lifetime of desperate that was probably all of two seconds, he brought a foot up so high it was nearly touching his behind, found a foothold, tested it and propelled himself forward on one leg. Scrabbling at the earth and roots and grass he wriggled forward on his belly and dragged himself to the blessed sanctuary of flat ground and grass. Rolling on his back, Squinter stared up at the sky and waited for the frantic rising and falling of his chest to slow.

You may or may not be surprised to learn that Squinter made the ascent perhaps another four or five times with his pals, the fear always intense, but tempered a little more every time by experience and familiarity with the route. He did manage, though, to avoid the climb on the vast majority of visits to Colin Glen by peeling away from the main group with a few friends before the cliff hove into view on some pretext or other.

Squinter now rather suspects the kids willing to join him on the breakaway welcomed the chance to avoid the cliff too. Dissidents they might have called us in another era.