NEXT week will mark 40 years from the end of the 1981 hunger strike. Much has been written this year and many events have taken place to remember those who died. For me Ten Men Dead by David Beresford and Nor Meekly Serve My Time, compiled by Brian Campbell, remain two of the outstanding books of that period. Jim McCann’s 6000 Days is a very welcome and amazing recent addition to these publications. A must read book.

So too with another new book – The Comrades – just published by An Fhuiseog as part of the work of the ‘81/21 Committee’. This collection of reflections provides a rare insight into the 12 republican prisoners who died on hunger strike during the most recent phase of the long struggle for Irish freedom. Pádraic Wilson was the dynamo behind its publication and Danny Morrison edited it.

1981 was a watershed year in our history: the heroic resistance of the women in Armagh Gaol and the men on the blanket in the H-Blocks; and the support of families and communities across this island and internationally who rallied in support of the hunger strikers.

The Comrades deals less with the politics and more with the humanity of the hunger strikers. It is a powerful piece of work. It is a selection of accounts of each of the hunger strikers by those who knew them. The writers were all prisoners and lived through those difficult years. The emotion and memories that The Comrades evokes were evident last week at two events to launch the book. One in the Andersonstown Social Club and the one I attended and spoke at in Tí Chulainn, South Armagh.

Laurney McKeown, who spent 70 days on the hunger strike, writes about Mickey Devine. Paddy Quinn, who was 47 days on hunger strike, writes about Raymond McCreesh. Both were in Tí Chulainn. And because we were in South Armagh I thought it appropriate to focus my remarks on Paddy Quinn and on his comrade Raymond McCreesh, with whom he was captured in 1976. I met Paddy in August 1981 when Owen Carron, Seamus Ruddy and I went in to the prison hospital to speak to the hunger strikers and to tell them that if they chose to end the strike that we would support their decision.

Paddy started the hunger strike on June 15 and he was the 11th hunger striker. During the meeting – which included Laurney – Paddy, who was sitting in a wheelchair, told us that his sight had gone. I went and spoke to him privately.

Paddy said to me: “Ná bac. Lean ar aghaidh.’ (“Don’t bother. Keep going.”)

In an interview Paddy recalled: “I wouldn't give up. Maggie Thatcher wasn't going to criminalise me.”

Paddy explained how painful the hunger strike was. “I could feel this terrible pain. A medical orderly was helping me to breathe, but I was hallucinating. I could hear the noise in my throat, gasping for breath. I was watching the deterioration of my body, thinking, ‘I have to do this; I'm going to keep going.’ It was just pain, day after day. Then one day I went for a shower, I collapsed in the shower, then there was the sickness. That was maybe after 43 days, in and out of consciousness at that stage. I had reached that point that I was looking forward to death. I felt a real sense of contentment. I had accepted I was going to die and I was happy with my decision.

“If the British had succeeded in criminalising us, we would never have got over it,” said Paddy. “If Sinn Féin had remained hard-line and military, then I think the sacrifices made on the hunger strike would have been a complete waste. It was Sinn Féin going into politics that made it worthwhile.”

Paddy subsequently had to have a kidney transplant. His eyesight was damaged by the hunger strike. When asked if he had any regrets he said: “I remember somebody saying to me once, ‘You lost 10 years.’ I said, ‘In those 10 years I probably had more experience than you'll ever have.’”

Original #HBlock 1981 #Hungerstrike poster of the type carried during demonstrations or pasted on walls in support of the prisoners. pic.twitter.com/tOc76BEzbz

— 1981 Hunger Strike - 40th Anniversary (@198140th) March 27, 2021

In his account about Raymond McCreesh Paddy remembers his friend and his decision to go on the hunger strike. “From the start of his protest Raymie had not taken a visit with his family or anyone else because he wouldn’t put on the ‘monkey suit.’… I often think of how hard it must have been for Raymie and his mother, on their first visit in four years when the news he had to convey to her was that he was going on hunger strike… I was in the washroom in the shower when one of my comrades came in. He told me that news had just come through that Raymie had died a short time earlier.

“I was glad I was standing in the shower. It meant that neither the screws nor anyone else could see the tears that I shed for my comrade and friend Raymond McCreesh.”

The Comrades is an evocative, inspiring, emotionally moving account of the lives of 12 amazing men.

Laurence McKeown – a very fine writer and poet – in his essay in the book about Mickey Devine sums up the spirit of selflessness and courage that was and is the story of the 1981 hunger strike: “Regardless of our individual pasts, family histories and the various routes we took that eventually led us to the H-Blocks, we became a ‘family’ in prison. A family of blanket men. We didn’t identify those on hunger strike as being either IRA Volunteers or INLA Volunteers. It didn’t matter who they were, what organisation they belong to, what part of the country they were from, what they were charged with, or how long they were serving. They were blanket men. They were friends. They were brothers. They were Bobby, Frank, Patsy, Raymond, Joe, Martin, Kevin, Kieran, Tom and Mickey.”

In a final tribute to Mickey Devine, Laurney’s poem ‘Red Mick’ is an appropriate conclusion to the humanity and compassion and love which was as much a part of the prison protests as the politics.

For I believe that in the H-Block you found

Something to love and live for

A place to give what was yours to offer

And not be judged by societal norms,

Exalting the few and damning the multitude.

And you loved and lived that so much

That you loved and lived it

To death.

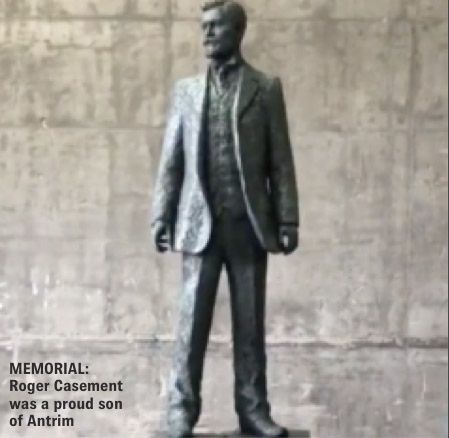

Dún Laoghaire Casement statue a very fitting tribute

LAST week an imposing bronze statue more than three metres in height of executed 1916 leader Roger Casement was lifted into position atop a tall plinth at a new jetty in Dún Laoghaire, outside Dublin. The statue is part of a new works project to refurbish Dún Laoghaire Public Baths. When it is completed a new jetty will have a studio space for artists, a café and a gallery.

Casement was born in nearby Sandycove in 1864. His activism as a humanitarian are legendary. He exposed the horror and brutality of the Belgian King Leopold II in his exploitation of the territory now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. In his greed Leopold murdered more than ten million people and millions more, including children, were maimed. Their hands and feet cut off if they failed to obey the orders of his overseers.

Leopold tried to keep others out of the region but the stories of torture and slavery and abuse gradually emerged. However, it was the work of Roger Casement which convincingly exposed Leopold’s reign of terror and brought it to an end. (He was knighted for this work and his work in Latin America.)

Roger Casement was raised in and around Ballymena in County Antrim. He was a member of an Ulster Protestant family and a British diplomat. He was also a Gaelgeóir who loved the Glens of Antrim. It is very fitting that Antrim’s county ground – soon to be rebuilt – bears his name. He was proud to be Irish. In more recent years gay rights groups have embraced Casement.

In 1913 Casement helped found the Irish Volunteers. He travelled to the USA to raise money for that organisation and was involved in the smuggling of weapons into Howth in July 1914. Casement negotiated with the German government during the First World War for more guns and assistance for the planned rebellion.

However it was his record of work as a diplomat, a senior public servant for the British Empire for which he awarded a knighthood which almost certainly sealed his fate in August 1916. To the British establishment he was a traitor.

Roger Casement was hanged on August 3, 1916. The last 1916 leader to be executed. Although his remains were eventually returned to Ireland in 1965 to be buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, his own wish was to be buried at Murlough Bay on the north coast of Antrim. In his last words from the dock Casement said: “This is the condemnation of English rule, of English-made law, of English government in Ireland, that it dare not rest on the will of the Irish people, but exists in defiance of their will: that it is a rule, derived not from right, but from conquest... I am proud to be a rebel and shall cling to my ‘rebellion’ with the last drop of my blood.”

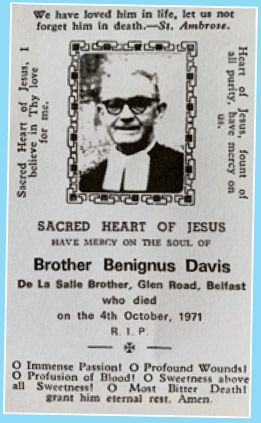

Wanted: Your memories of Brother Benignus (RIP)

A CORRESPONDENT has written to me looking for information on his great uncle, a De La Salle Brother.

Brother Benignus taught in Saint Finian’s Primary School on the Falls Road. I mention him briefly in Falls Memories, one of my books. He was a regular feature at hurling practice in the Falls Park in my youth, long into his retirement. I also recall him, a tall angular figure, walking along the Falls and Glen Roads.

But he never taught me so I am appealing to any older Saint Finian’s boys who may have been taught by Benignus or who were in his hurling teams to get in touch with the Andytown News, who will pass it on to me.

This is a long shot. Brother Benignus was born in 1889 in County Laois. He died in October 1971 in Belfast. Joe Kelly, who I have lost contact with and who taught in Saint Finian’s, or some of the older Naomh Gall lads or someone from the La Salle Order may have some scéal.