“THE people here mostly live by weaving and mostly all Protestants…Many of the people I met within this district seemed to know well and pride themselves in the fact that they are Protestants, yet it appeared to me that they do not know much of their Bibles.”

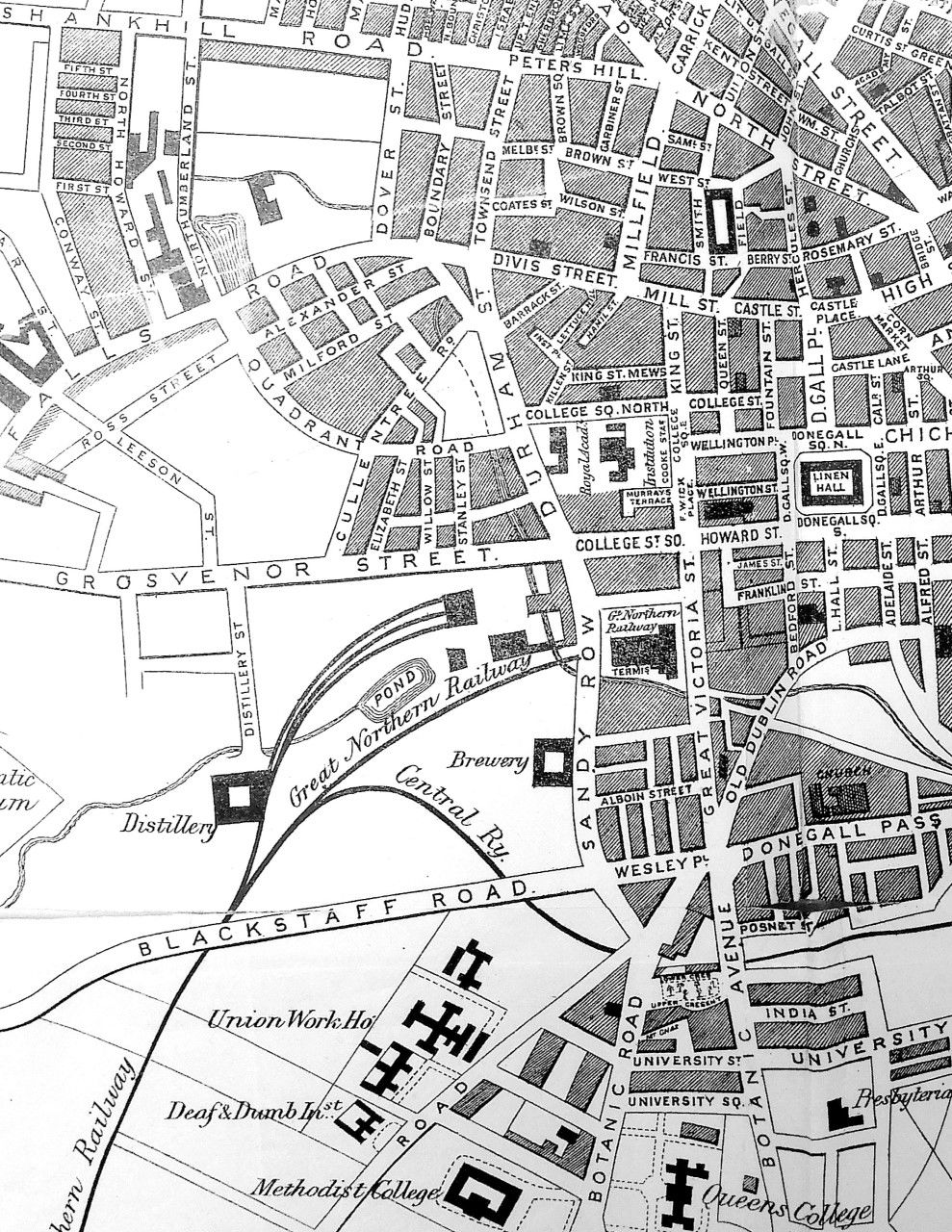

This frank but enlightening observation about the district known as ‘Sandy Row’, was written in the diary of Rev. Anthony McIntyre of the Unitarian Domestic Mission to the poor of Belfast, after his earliest visits there in 1853. One of Belfast’s oldest settlements, a late 18th century map shows it as little more than a small area of fields with some isolated dwellings, its name derived from the sandbank formed by the high-water mark, left with the flow off the tidal waters of the Lagan. Crucially it formed the southside entrance in and out of Belfast, to Lisburn and further afield to Dublin via Durham Street, and across the hills and by-ways of the adjacent ‘Old Malone’.

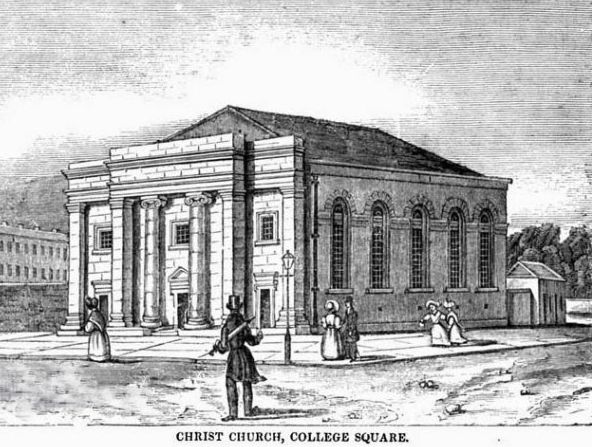

A sparsely populated suburb in early 1800, its expansion and population growth were later driven by industrialization, particularly with the textile industry. Over time it became a staunchly Protestant stronghold, facilitated by migrant labour and the building of Christchurch in Durham Street in 1833, with Rev. Thomas Drew as its first Minister. He later stated in 1868, “If any man ever writes a history of Belfast, he will have a very strange story to tell of the Sandy Row district. I can remember 40 years ago, when a more neglected people would not be found on the face of the earth. No man seemed to care for them, and the poor people were left without religious instruction.”

Later, Sandy Row became a strategic centre for the expansion and influence of Orangeism; its Orange Hall at its southern entrance completed in 1869. Its famous Boyne Bridge crossed the Blackstaff River, north-side with Durham Street. One of its most well-known and ‘infamous’ buildings was the Belfast Union Workhouse, located off Donegall Road. Opened in 1841, it was built to house a maximum capacity of 1,000 inmates; its graveyard in two sections, located behind Utility Street and Abingdon Street. With 19th century industrial development, its most notable manufacturing bases were the Linfield Spinning and Weaving Mills, Richview Brick Works, Royal Irish Distillery, Malone Felt Works, the Ulster Brewery, and Murray’s Tobacco Works.

Christchurch, 1830s, Durham St, 1830s (www.emeraldancestors.com)

A most unusual feature of social and cultural significance for Sandy Row was revealed in Rev. McIntyre’s diaries, observing in 1853 the following peculiarities, “…the people here seem to be under some kind of enchantment about ghost stories…finding money and the like…Many other strange tales I heard.”

This strange phenomena of the “gold diggers” of Sandy Row was also documented by Rev. W. M. O Hanlon, visiting at the same period. He found that groups of men for some years, were regularly digging around the heights and slopes of the Cave Hill at all hours, convinced that chests of gold treasure were buried and left there in haste, as the Danes (Vikings) left their settlements in the North before fleeing to elsewhere in Ireland.

“Night after night…in the midnight hour; Oberon and Titania Puck, Peas-Blossom, Robin Good-fellow…whom Shakespeare has immortalised in his immortal “Dream,” have found willing followers in this neighbourhood, and led them a mystic dance for gold to Cave-Hill.”

Disapprovingly, he said of their character, “…they themselves are tossed and agitated in mind by day and by night – feverish and dissatisfied with a life of ordinary industry and toil. The dream of sudden and inordinate wealth has maddened them, and they are ready, if that were possible to sell their souls for gold.”

The Famine Years

The Great Famine profoundly affected Belfast, particularly its poorest, most vulnerable inhabitants. Sandy Row was part of the College District – one of the town’s six medical Dispensary Districts. On February, 12th, 1847, as the typhus fever epidemic raged, Dr S. Browne, Medical Attendant for the College District, described its levels of destitution, “…the amount of misery presented among the individuals whom I’ve been called on to visit, has been appalling…I have lately seen many families deprived of every necessary of life: devoid of fuel, personal and bed clothing, without beds, whereon to stretch their famished frames and with barely enough of soup to ward off immediate starvation; their houses – such wretched abodes! …a picture of desolation and distress that I have never seen equalled in any part of the world.”

In 1847, almost 1,000 were suffering from fever in the College District; half of which came from just ten localities, including several parts of Sandy Row and adjacent streets – Durham Street, Pound Street, Hamill Street, and others. On February 13th, 1849, the Northern Whig published Dr Browne’s letter – ‘Cholera and Sanitary Reform’. “...wherever the disease has been, there have I found pent up drains, poisoning the surrounding air, cesspools filled with disgusting nuisance, and a total disregard to every sanitary principal and regulation…there has the disease been more frequent, and much more fatal in its attacks...Take for instance, Lennon’s Court, off Smithfield. There the disease had spread most rapidly, and with great fatality. Again, let us look at Tea Lane and Sandy Row. In both, cases of cholera have been numerous, and, in many instances fatal: both of these localities are notorious for filth, and its sure accompaniment, disease!”

Sectarian Conflict, 1864 Riots

Sandy Row had a reputation for aggression and its association with sectarian conflict with neighbouring Catholic/nationalist districts, notably around the Pound-Loney; the worst riots occurring in 1835, 1843, 1857, 1864 and 1872. Even the Rev. W. M. O Hanlon stated of his pastoral visit to Sandy Row in 1852:

“This locality in not unknown to fame…I confess it was not without at least, a momentary trepidation that we ventured into this region. I had heard of its bludgeon men, and, even though on a peaceful mission, I thought it just possible we might fare ill among men of blood…”

The divisive nature of the religious and theological movements within the Catholic and Protestant churches were well known and understood, as with politics in mid-19th century Ireland. The Catholic Church, recognised supreme papal authority in matters of spirituality and governance, promoted especially by Dr Paul Cullen (1803-1878), Catholic Archbishop, later the first Irish ‘Cardinal’. Conversely Belfast became the centre of the ‘1859 Protestant Evangelical Revival’, also termed the ‘Second Reformation’. A place for powerful and influential Protestant preachers beginning with Dr Henry Cooke in the earlier 19th century, later followed by fiery Protestant ministers, including ‘Roaring’ Rev. Hugh Hanna and Rev Thomas Drew, fanatical believers and preachers of the Pope as the ‘Anti-Christ’ and infamous for stoking the flames of sectarian passions.

‘Immediate trigger events’, amidst traditional religious and political antagonisms of both communities, were usually the focus of newspaper reports of the riots, but often differed significantly in their accounts of the causes and responsibility for the violence. The 1864 August riots in Belfast, lasting several weeks, were widely reported in the press as probably the most vicious conflicts experienced between Protestant Sandy Row and adjacent Catholics districts at Barrack Street, the Pound district, Smithfield and Millfield. Many hundreds were involved in gun battles, street riots, hand to hand fighting, arson, countless wrecked homes, with fatalities and scores severely injured.

The Londonderry Standard, August 17th, 1864 described Belfast as in “A State of Civil War”, with fatalities and numbers of severely wounded during riots of “gigantic proportions.”

A Daily Express reporter was quoted in the Kilkenny Moderator of August 17th, stating of the riots, that much of the blame lay with the violent proclivities of the Catholic inhabitants of the ‘Pound District’, whom he branded as the “Pound Street Mob.” Whilst the Orange Order and other ‘respectable inhabitants’ in town, he alleged, did all in their power to prevent the violence, blaming the riots involving Sandy Row on the surrounding Catholic/nationalist localities in the most disrespectful and slanderous manner,

“… unfortunately exists a gang of low, ruffianly, ignorant millworkers, who, with little or no acquaintances with the principles or practices of the faith they pretend to profess…To this class of persons must be attributed the disorder that brings the name of Belfast into disrepute. The scum of these people live in localities known as the Pound Loney, Barrack Street, Mill Street, Millfield and Smithfield…remarkable for and differing from the remainder of Belfast in being the dirtiest and least improving as regards not only their appearance but their inhabitants. These are essentially the quarters in which the low Roman Catholic population live.”

In reality, it was the Orangemen and Protestants of Sandy Row who incited wide-spread violence in Belfast, also known as the “Orange Riots”, after the massive event in Dublin on August 8th, 1864 planned by Dublin Corporation – the laying of a foundation stone for a memorial to be erected in honour of Daniel O’Connell, the ‘Liberator’; celebrated by nationalists from across Ireland.

In contrast he praised, “…the far-famed Sandy Row, of undeserved ill repute, the only crime of the locality being that the inhabitants are almost all Protestants.”

In reality, it was the Orangemen and Protestants of Sandy Row who incited wide-spread violence in Belfast, also known as the “Orange Riots”, after the massive event in Dublin on August 8th, 1864 planned by Dublin Corporation – the laying of a foundation stone for a memorial to be erected in honour of Daniel O’Connell, the ‘Liberator’; celebrated by nationalists from across Ireland.

That same night up to 5,000 Sandy Row Orangemen and supporters held a provocative counter-event, making a huge mocking effigy of O’Connell, which they burned on the Boyne Bridge. This provocation was the ‘first incident’ that sparked many subsequent nights of rioting in the College District. The next day the same crowds procured a coffin and led by a man mimicking a priest, placed the ashes of the burned O’Connell effigy in the coffin and proceeded in a vast mocking funeral procession to Friar’s Bush Catholic cemetery to ‘bury’ the coffin, but were prevented from doing so by armed caretakers at the cemetery who refused to open its gates.

The mob returned to Sandy Row, hurling the coffin over the Boyne Bridge into the River Blackstaff; the final contemptuous insult to the Catholic population of Belfast. Subsequently many nights of ferocious rioting ensued, between Sandy Row and the Pound and neighbouring Catholic districts with appalling outcomes on both sides – severe displacement of families and workers, widespread destruction of homes, with 3,000 military and 1,000 police placed in Belfast to restore order. The official Inquiry on 30th November revealed 316 civilians injured, including 98 of gun-shot wounds and 11 fatalities.

The Sandy Row Orange Hall

The foundation stone laying ceremony for the building of Sandy Row Orange Hall occurred on 4th July, 1868; the official opening ceremony of the completed building took place on 24th September, 1869. Speeches were made by high-profile officials, including the Rev. Thomas Drew at the former and the Rev. Henry Henderson of the Presbyterian Church of Ireland, at the latter. The Rev Thomas Drew ended his speech with his own ‘poem’ attracting the attention of the nationalist journal ‘The Nation’, (July,11,1868).

“The Orange lodges…seem very much in the same plight as the London Music Halls; they have been the cause of much singing and yet they have not produced a single poet”. Quoting Rev. Drew’s final verse, ‘The Nation’ stated, “It is a pity we have no better troops for our Protestant garrison in Ireland than fanatics and fools of this description”-

“Oh, Sandy Row! Oh, Sandy Row!

My heart is there where’er I go;

The rivers they shall cease to flow,

Ere I forget thee, Sandy Row.”

Along with standard rhetoric about ‘civil and religious liberties’, the Boyne, popery, and the Reformation, key issues emerged within the speeches indicating how Protestant preachers and the Orange Order viewed the vital and strategic importance of Orangeism. A critical issue was the imperative of keeping Protestant working class men and women closely aligned to the Orange Order, its lodges and halls, to exert an unyielding, powerful cross-class Protestant/Orange alliance for maintaining the political Union and the advancement of Protestantism and its influence. At the foundation stone laying ceremony, Stewart Blacker, Chairman, described Orange Halls as places, “...where we can utter loyal, and proper sentiments; and they will not be lost, for they will go forth through the length and breadth of the land and I should be glad if the whole length and breadth of Ireland was one Sandy Row. We would have no Fenians then”. (Loud cheers and laughter).

Sandy Row Orange Hall. Photo by Brendan Muldoon

Significantly the ceremony’s ‘dignitaries’ included a deputation from the ‘Belfast Orange & Protestant Working Men’s Association’. Formed in 1868, this organisation was designed to thwart the development of a united working-class labour and trade union movement that could overcome Belfast’s traditional religious and political divisions, the great fear of Orangeism. Likewise at the 1869 opening ceremony, the Rev. Henry Henderson of the Presbyterian Church of Ireland, stated: “So long as the fair women of Ulster are attached to Orangeism there is no doubt of its ‘stability and prosperity’…in the demonstrations of last July, tens of thousands of them…appeared commemorating the time-honoured anniversary of the Glorious Twelfth.” (Cheers).

The Rev E.J. Hartrick concluded the ceremony, ‘generously’ stating that the Orange Order had no desire to expel the Papists from Ireland, “but that they should convert them to Protestantism…their duty was to bring the truth before every Romanist, leading them from darkness to light.”

In ‘Walks Among the Poor of Belfast’ (1853) the Rev. W. M O’Hanlon, outlined his hopes for the future of Sandy Row, “Let secular and religious education be provided for the people, and Sandy Row will soon have another sort of celebrity than that unenviable one which it has hitherto possessed. Belief in magical arts and incantations, digging in the night for Danish gold, club law, political brawls, and other evil works of this description, will give place to intelligence, domestic quiet, sober and industrious habits, moral and religious worth; and the very aspect of the people and of their dwellings will whisper the change, in no doubtful accents, as the stranger passes along to learn and study the form and features of their social situation.”

Brendan Muldoon©2022