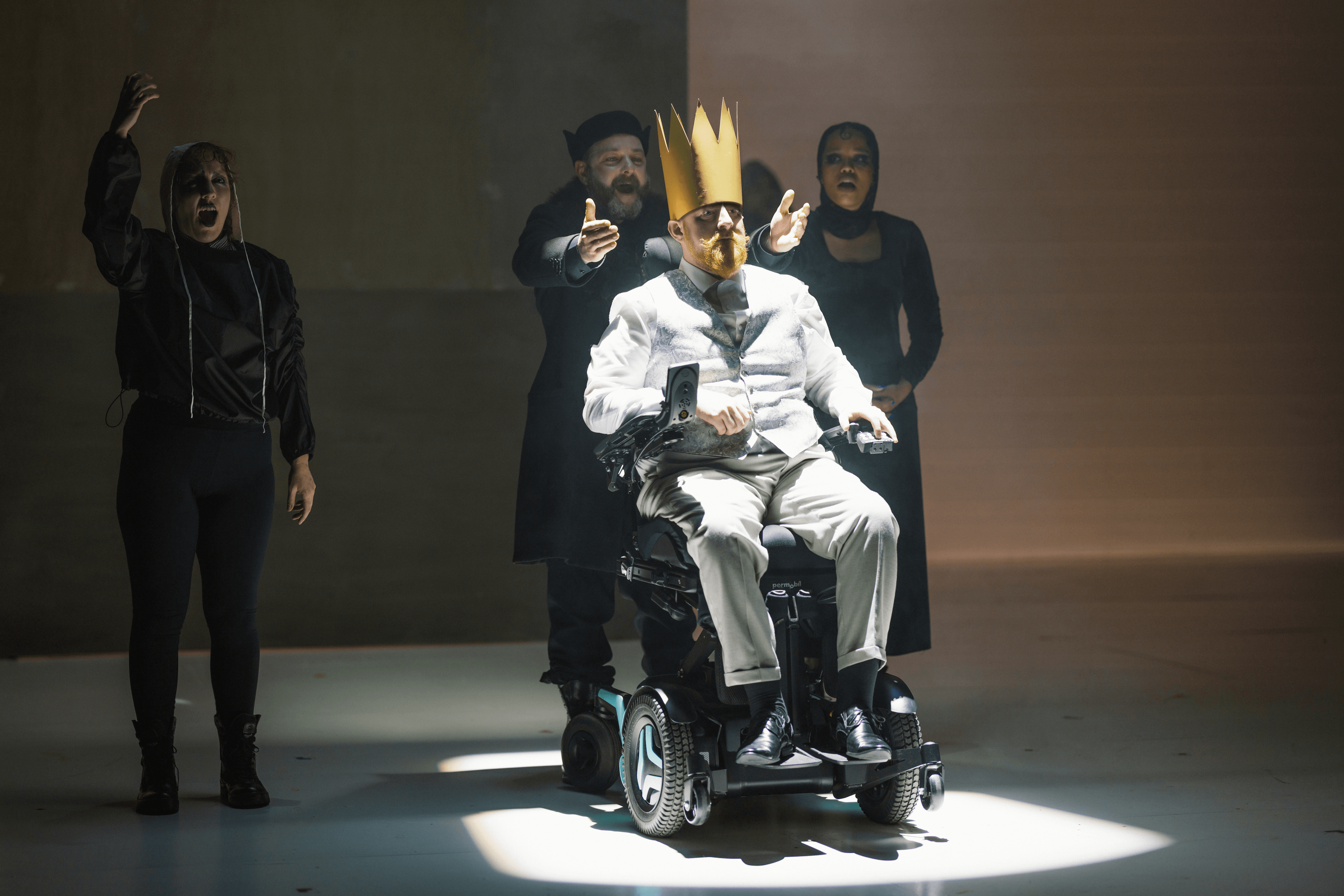

A MONARCH in an electric wheelchair wearing a Burger King cardboard crown. The Wars of the Roses fought with pikes and pepper spray, swords and perspex riot shields. Bodies dumped in a wheelie bin, royal ladies in Doc Martens.

The arrestingly hybrid style of The Tragedy of Richard III, which opened at the Lyric on Wednesday night, is hardly the first time a production of a Shakespeare tragedy has swapped or traded lavish costumes and exaggerated courtliness for gritty modernism and urban argot, but it’s triumphant confirmation that the Bard’s eternal themes can be given added zest and relevance when yanked from their castellated comfort zone.

Michael Patrick takes the lead role of the savagely ambitious would-be king, embittered and enraged in equal measure by his disability, traditionally manifested in the malignant cliché of withered arm, hunchback and ostentatious limp, but here represented simply by Patrick’s wheelchair. It’s a much more common and altogether less melodramatic symbol of disability, but its very familiarity allows us to see better the emotional carnage behind the physical facade. It’s an opening that Patrick grabs with both hands, particularly in the final scene.

To describe the set as spare would be to seriously underplay its eyebrow-raising simplicity. A roughly painted plywood tower with deliberately visible supports and wheels; a large set of wooden of steps. And that’s it. Oh, apart from a blink-and-you-miss-it, rapidly-deflated bouncy castle in the opening scene.

DRAMATIC: The battle scene gripping and highly stylised

While the tower simply looms hulkingly over the action, blocking light and allowing it in according to mood, the steps are a theatrical Swiss Army knife: Now a seat, now a bed, now a table, now a gallows – now even... a set of steps. Around these, the players rolled out Shakespeare’s brutal and poignant family drama, perhaps slowly and a touch uncertainly at first, but building in confidence and pace until they dragged us by the scruff with them into the middle of the climactic and magnificently stylised battle scene.

The ensemble delivers a deeply satisfying mélange of drama, comedy and tragedy as around Richard the plotting and counter-plotting of the York and Lancaster camps play out – at times traditionally formal, at times camply pantomimic, but always engaging.

ARRESTING: Chris McCurry as Stanley and Ciaran O'Brien as Clarence

Special mentions to Paula Clarke as the sign-language serial killer Tyrrell, who veers dizzyingly between low comedy and dark menace to keep us constantly off balance; Ciaran O’Brien, who grabs us by the lapels with his Clarence – an ever-intriguing portmanteau of Will o’ the Wisp and manacled, pitiful victim; and Charlotte McCurry, who manages the not inconsiderable task of investing one woman with a bewildering range of characteristics on a spectrum which arcs from strong-minded to vulnerable. (Declaration: Charlotte’s my niece. But did I tell you she’s wonderful?)

Director Oisín Kearney has taken a technically difficult work and laid it out in an accessible, entertaining and affecting form, managing at the same to platform disabled players and themes without a trace of tokenism. The sense of drama and doom is built carefully and skilfully, crescendoing thrillingly with the considerable aid of an ambitious reliance on fairly heavy percussion, which proved in the end an adept choice.

A standing ovation and a double curtain call from a packed theatre was the Belfast verdict on this sumptuous order of Burger King Richard.