A NEW book that tells the story of Belfast’s 1932 Outdoor Relief riots will be launched at the MAC theatre next Tuesday.

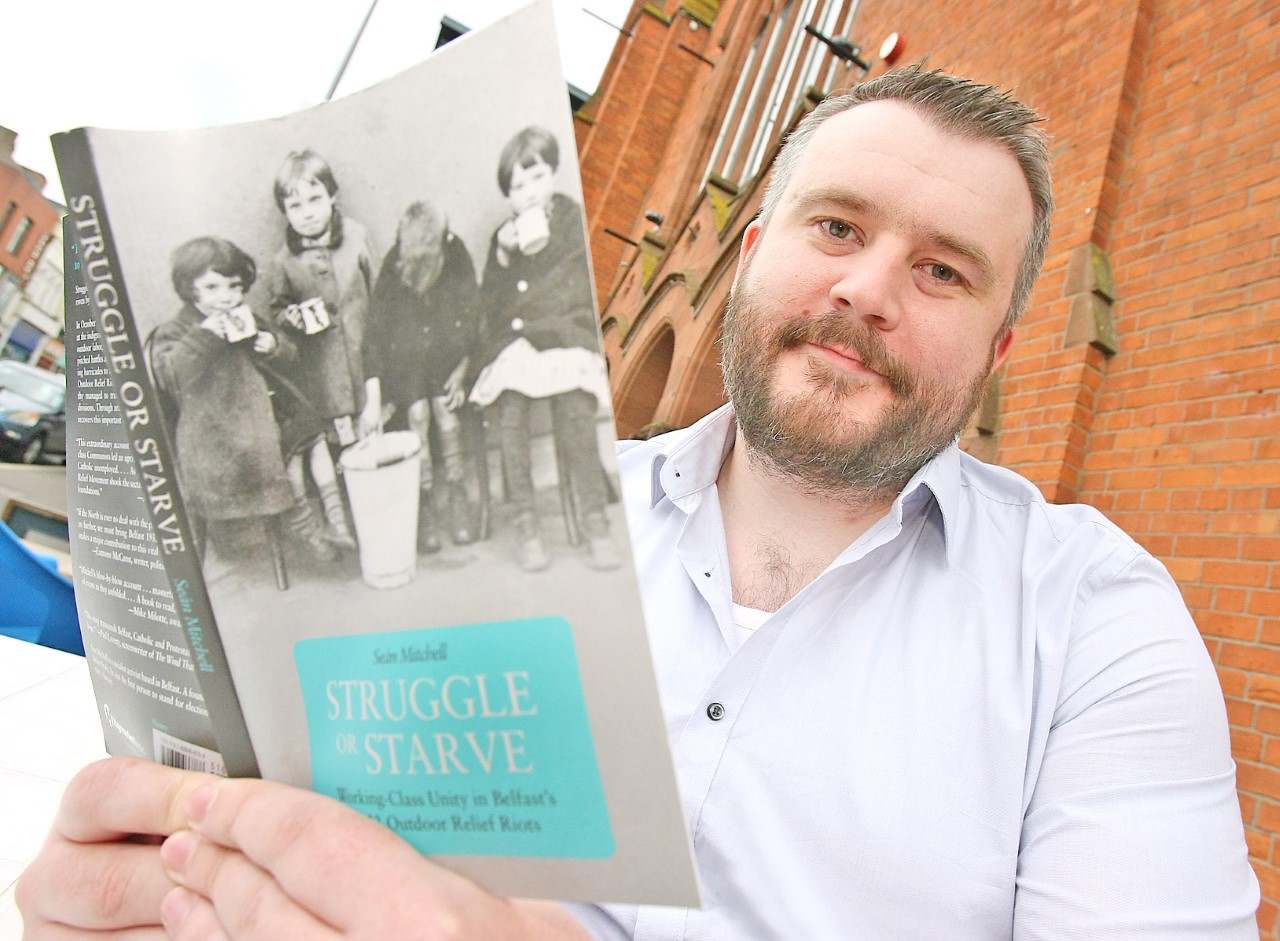

Written by Andersonstown man Seán Mitchell, ‘Struggle or Starve’ documents the fascinating events that took place during a time that saw working class Catholics and Protestants unite to oppose the government’s draconian Poor Laws.

The riots unfolded against the backdrop of abject poverty and widespread hunger. The Poor Laws enforced by the sectarian Northern government did not distinguish between the tens of thousands of workers, both Catholic and Protestant, who were driven to the brink of starvation.

With unemployment levels in the six-counties reaching a staggering 40% in 1932, a group of communists called the Revolutionary Communist Group (RCG) organised a mass campaign of strikes and demonstrations that would eventually lead to two days of rioting.

The stark conditions that contributed to the riots of 1932 and the events themselves are undoubtedly fascinating, but Mitchell said that their significance has often been overlooked – a factor that inspired him to write the book.

“I was vaguely familiar with the outline of the outdoor relief riots and I knew that it was a period where Catholics and Protestants were said to have come together for a mass strike, but what I discovered when I started the research was that it was a far more significant event than what people might presume,” he said.

“It was an event that included mass scale rioting, the erection of barricades, gunshots, death, and effective martial law on the streets of Belfast. There were 17 people who were shot during the riots and yet there are no murals, no statues, no annual commemorations for the event, and some of it happened here in West Belfast, on the Falls Road, and various other places around this city, so there was obviously a void that needed to be filled – that’s partly why I wrote the book.

“I think that events only tend to remain in popular memory if some force or group has an interest in keeping them alive. That raises the question: in whose interest would it be to keep the memory of the 1932 Outdoor Relief riots alive? It’s not particularly in the interests of unionism to keep it alive, and it’s questionable whether it is in the interests of nationalism to talk about it.

“Obviously we have always had a very small socialist movement here, but I don’t think the Outdoor Relief riots were ever part of the narrative of the two main traditions and therefore nobody kept it alive – the story had to be retold.”

Seán noted that the neglect of Belfast’s shared working class history can also be reflected by the little-known stature of the leader of the Outdoor Relief Strikes, Tommy Geehan.

“One of the important things about the book is that it rediscovers the name of Tommy Geehan and shows his stature,” he stated.

“If you think of Jim Larkin for example, he is world renowned as the leader of the 1907 dockers strike and the 1913 Lockout – Tommy Geehan did everything that Jim Larkin did in a sense, and maybe even more because the strike that he was the leader of was actually successful – Jim’s wasn’t so much a success.

“Yet again there are no murals or statues of Tommy Geehan, very little is known about him, but he is a remarkable figure. He began his life in the republican movement and eventually became part of the communist movement. He led a life that should be of interest to anybody.”

Far from being from a simple statement of facts, Mitchell’s new book offers an historical materialist analysis of the Northern state and its society that exposes the deep-seated, systematic sectarianism that has divided the working class.

“You have to understand the Northern state and indeed the southern state as something that emerged from the counter revolution in Ireland,” Mitchell explained.

“Both were, to some degree, mirrored states; you had a conservative, right wing Orange state in the north, and a conservative, right wing Catholic state in the south. The Northern unionist state set out to use sectarianism to strengthen its position and to enforce partition, but also to divide the working class and to strengthen the new state’s position as a leader in industry.

“Partition allowed the elites to divide Ireland, but it also allowed the industry elites to divide those in the shipyards and those in other workplaces that might oppose them. The events of 1932 have to be understood against the backdrop of 12 years of sectarian agitation from the elites to keep people divided. Understanding that backdrop allowed you to properly access the significance of the event.”

While ‘Struggle or Starve’ brings an important piece of forgotten history to life, Mitchell hopes that the history book can also serve as a practical lesson for the working class of today.

“There are no easy and fast historical analogies that can be made between then and now, but there are obviously echoes of the Depression era today,” he said.

“I talk about this in the book, but if you think about the way that the unemployed were treated and constantly degraded, how unemployment was described as an individual’s problem – that unemployed people are lazy or unqualified – then you can draw parallels with today when you think of benefit cuts, welfare reform and the way that the unemployment problem is described by the right wing.

“The events of 1932 are unlikely to be repeated in the exact same way, but there are lessons to be learned about the way in which people were treated by the government and also about the way that those people organised and resisted.

“I don’t think levels of poverty or levels of deprivation dictate working class struggle. Struggle usually emerges because people’s level of expectation rises. If people expect that they should be getting a better deal or that there is an injustice occurring, then there is always the possibility of that struggle emerging, regardless of whether they are living in abject poverty or not.

“The question is: can we raise people’s expectations and can we show that people’s conditions can be improved or that the way that society currently runs can be changed. If you think about the rise of Jeremy Corbyn for example, it’s predicated on the idea of some basic changes such as free education and proper healthcare – what he has done is he has raised people’s expectations. What happened in the 1930s was that a small group of communists raised people’s expectations of a better life.

“The fact that this book reveals a different style of politics, a different past and maybe a different future, shows that these things need to be highlighted. It is presumed that all history is of the orange or green narrative, but these events show that there is another thread to our past and the more we draw that out the easier it is to build that future.”

The ‘Struggle or Starve’ book launch at the MAC will take place at 7pm on July 4. Event includes video footage and dramatic readings from the period as well as light refreshments and a short introduction from the author.