It does not feel as if history is being made in Scotland. Not on the streets, anyway.

In just three weeks the country goes to the polls. At stake is the very future of the United Kingdom.

How so? Because the ruling Scottish National Party is trying to achieve an overall majority and what it sees as mandate for a second independence referendum.

Yet with Scotland only slowly emerging from a coronavirus lockdown, this campaign is deceptively low-key.

There are no live hustings, no rallies, no marches, no protests and few unscripted pavement encounters between candidates and voters.

Even photo opportunities are suitably sanitised and socially distanced: in this election babies are going unkissed.

What a wonderful morning!

— Sarah Masson (@_sarahmasson) April 20, 2021

☕️ Coffee,

🧁 Cake and

🤩 @NicolaSturgeon

(Maybe even worth rescheduling a much needed haircut for 😜)#BothVotesSNP #TeamSNP #MassonForEdWestern pic.twitter.com/xkpOaNMWj7

There has been some action: leafleters claim to be suffering from more dog bites than usual, thanks to all those pets bought during the pandemic; animals which are not used to gaudy election material being pushed through their letterboxes.

And there are, occasionally, flags, to remind us of Scotland’s competing nationalisms, its rival or overlapping national identities. Saltires are blue-tacked to tenement windows and Union Jacks run up poles in the back gardens of suburban semis.

Boris Johnson, remains toxic in Scotland. The Prime Minister is staying away from the Scottish campaign. But it will be Mr Johnson who has to decide whether to try and block Ms Sturgeon’s demand for indyref2.

What is this election about?

FIVE times I asked @Douglas4Moray to spell out the democratic path to holding #indyref2@Channel4News

— Ciaran Jenkins (@C4Ciaran) April 19, 2021

pic.twitter.com/LMnEu5zPnr

Scottish politics can be bitter and polarised. But there is one thing all sides agree on: the current campaign is about whether there should be another independence referendum or not.

It is six-and-a-half years since the SNP and their allies lost a first big vote, the so-called indyref. The score was 45 per cent for independence and 55 per cent for union.

Swing voters were nervous about issues like currency and European Union membership. They still are. But now they are also worried about Brexit. And that has changed the electoral maths.

As in Northern Ireland, the UK leaving the EU has challenged old certainties. Independence now routinely polls just ahead of union.

But the election on May 6 for Scotland’s devolved parliament, Holyrood, is far more than an opinion survey. It is the biggest test since the 2016 Brexit referendum of the strength of Scotland’s pro-EU nationalism.

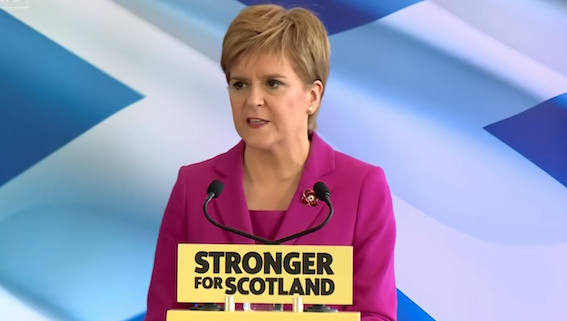

Nicola Sturgeon, the SNP leader and first minister, has set out a clear offering. Launching her manifesto last week, she said she was seeking a mandate to hold what in Scotland has become known as indyref2 by 2026.

📜 King @RobertTheBruce endorses the @AlbaParty.

— ALBA Party (@AlbaParty) April 11, 2021

As in 1314, it will be the 'Sma Folk' who will win the day for #Scotland in 2021.

For the independence #Supermajority, make your #ListVoteALBA pic.twitter.com/bVAJvyFWoy

She has ruled out a new vote during the pandemic, saying it would be a "dereliction of duty" not to focus on Covid.

However, she added: “But it would also be a dereliction of my duty as First Minister - my duty to this and future generations - to let Westminster take Scotland so far in the wrong direction that we no longer have the option to change course.”

Ms Sturgeon’s sometimes allies, the pro-independence Scottish Greens agree. Three unionist parties - the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats - oppose any independence referendum, at least any time soon. But they do not shy away from Ms Sturgeon’s proposal being the issue of the election.

The Tories’ new leader, a football linesman and MP called Douglas Ross, hopes to mobilise the unionist base with what amounts to a 'Scotland Says No' message.

But this stance has problems too. This week, challenged by Channel 4 News, he could not or would not answer a simple question about what the democratic means for Scottish independence would be.

His Westminster leader, Boris Johnson, remains toxic in Scotland. The Prime Minister is staying away from the Scottish campaign. But it will be Mr Johnson who has to decide whether to try and block Ms Sturgeon’s demand for indyref2.

Who will win?

QUESTION ON MOST MINDS

Barring a miracle, the SNP will form the next government and Nicola Sturgeon will be first minister. The question on most minds is whether Ms Sturgeon can secure an outright majority, as the SNP did under her predecessor Alex Salmond in 2011, sparking the 2014 indyref.

Scotland’s electoral system makes it very hard for any party to take more than half the seats in Holyrood.

Everybody over 16 - including resident foreigners - gets two votes. The first goes on a first-past-the-post (FPTP) constituency. The SNP will win most of those. The second goes to chose a party on eight regional lists, proportionately. The results of the list elections are adjusted to reflect the results of the FPTP ones. That means it will be much harder for the SNP to pick up seats on the second vote. But it may well need to do so to get its majority.

I asked @NicolaSturgeon whether she has conducted an analysis of the economic consequences of independence pic.twitter.com/qI8YdJNl2z

— Ciaran Jenkins (@C4Ciaran) April 15, 2021

The latest poll, for the Sunday Times, suggests it will get the magic 65 seats. Other are not sure.

But there is a further complication: Mr Salmond, Ms Sturgeon’s predecessor and one-time mentor, has set up a rival pro-independence party. It is called Alba, the Scottish Gaelic for Scotland. And it is urging its supporters to vote SNP on the first vote, but for it on the second, to secure what it calls a “supermajority” for independence.

What impact will Alba have?

Scotland’s big politics story for early 2021 - aside from the pandemic - was over how the SNP and its government handled an investigation in to alleged sexual misconduct by Mr Salmond when he was first minister.

The one-time SNP flag-bearer was last year acquitted of criminal sex offences, which he has always denied. Some of his supporters allege he was framed, though they have failed to produce any evidence for this. But a government probe in to #metoo allegations was botched and, a court ruled, “tainted by apparent bias”.

INDEPENDENT WATCHDOG

Unionists had hoped the row over Mr Salmond would end Ms Sturgeon’s career. It has not. She was cleared of breaking the ministerial code by an independent watchdog.

Her approval ratings remain high. Mr Salmond’s are below those of Mr Johnson. He has his fans, however, including voters who believe Ms Sturgeon’s independence proposals lack urgency.

Alba could, even if it only gets five or six per cent of the list vote, collect some MSPs. Or it could just do enough to take a few votes away from the SNP and rob Ms Sturgeon of her majority. Or it could have no impact at all. This matters. Why? Because it will be much easier for Mr Johnson to put barriers in the way of indyref2 if the SNP, on its own, fails to secure a clear majority.