“Turn down this ‘shy thoroughfare’, which runs past the bank to St. Mary’s Chapel and in a moment, you gain the easy clarity of mind that comes from breathing an atmosphere loaded with the fragrance of the past.” (The Glamour of Belfast, H. A. Mac Cartan,1921.)

BANK Street in Belfast city centre has a fascinating history, with captivating stories of clandestine meetings, conspirators, narrow escapes, famous personalities and famous venues: Kelly’s Cellars, St Mary’s Hall, Bank Buildings, the Provincial Bank and, of course, the wonderfully iconic ‘Fresh Garbage’ clothes shop. It was also a populated street of private houses and families from all walks of life in the 19th and 20th centuries, from surgeon, to shoemaker to labourer, leading to the thoroughfare of Chapel Lane and the Smithfield district.

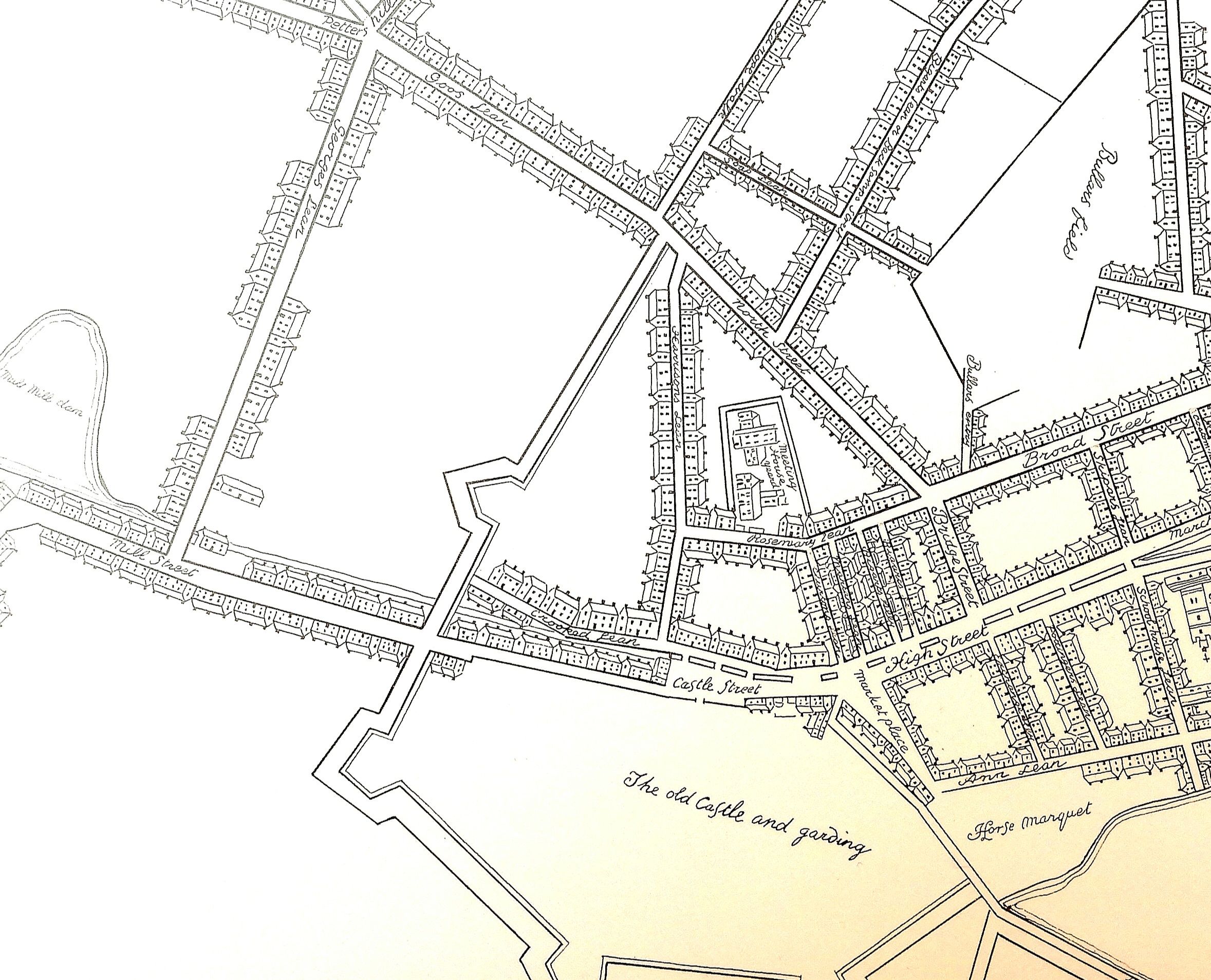

1715 Plan of Belfast showing Crooked Lane

Bank Street: development and famous residents

The 1660 Plan of Belfast showed the settlement as containing six streets and four rows of houses. Bank Lane did not exist then, its later location was shown simply as part of a flowing Farset stream. By 1791, a survey revealed that the number of quays, streets, lanes and entries had increased to 75 and by 1808 further increased to 114 and when Bank Lane first became a ‘populated location’. Some time in the early 18th century it was known as ‘Crooked Lean’ because of its shape.

On the Town Plan of Belfast of 1796, it was simply known as ‘Back of the River’ – a reference to the Farset that flowed along it in the direction of High Street. It’s shown as leading to Chapel Lane, marked on the map as the site of a ‘Romish Chapel’, and opposite the site of a Protestant ‘Meeting House’. Bank Street was known historically by other names including ‘Bank Lean’ and ‘Cunningham’s Row’ from the house and the bank financed by Belfast’s leading 18th century merchant and influential businessman Waddell Cunningham, both located at its entrance. An example of name changes can be seen with the address of the brewery listed in Belfast’s 1807 Street Directory as “William Napier, Brewer, 24 Back of the River” but in the 1819 Street Directory, it’s designated as ‘Bank Lane’.

Waddell Cunningham

Waddell Cunningham was the well-known wealthy Belfast merchant and businessman who settled in Belfast about 1763, living in Bank Lane until his death in 1797. It’s believed the site of his residence was occupied by the Buttle family from the late 1600s. David Buttle was Sovereign of Belfast until 1703.

After Waddell Cunningham’s time, the property was purchased by William Tennent, son of a Presbyterian Minister, in 1808, who replaced the existing property with a magnificent mansion. Tennent, a United Irishman, was imprisoned for his participation in the uprising in 1798. The large grounds attached to the house extended down Bank Lane for 243 feet and northwards in the direction of Berry Street. In the early 20th century, the property was purchased by several Catholic laymen who opened a reading room and library in the house and eventually sold a portion of the property to the Provincial Bank at the end of Bank Lane while the remainder was granted to the ownership of the Catholic Church; thus St Mary’s Hall was designed and opened in Bank Lane during the early 1870s It was Waddell Cunningham who with several others set up a private bank (later known as the ‘Old Bank Building’) at the top of Bank Street in 1785 to facilitate commercial activity with the emerging linen trade and other business activity. In retaliation for his land speculation and evictions in the northern parts of Antrim in 1771 his house in Bank Lane was attacked and destroyed by fire by members of the secret agrarian society ‘The Hearts of Steel’. Later, as preparations were laid for the 1798 Rebellion, Cunningham was prominent among the town's loyalists in volunteering his services to the local yeomanry.

Cunningham had also called a meeting of merchants and businessmen in 1786 to invest in Belfast’s port as a slave trading centre. Thomas Putnam McCabe, a United Irishman and prominent Belfast merchant, being a leading figure in the city's anti-slavery circle, stormed the meeting and stopped plans by the assembled merchants to set up a Belfast slave trading company, famously declaring: “May God eternally damn the soul of the man who subscribes the first guinea!” This put a swift end to any ideas of setting up Belfast as a slave trading port.

St Mary's Hall

Kelly’s Cellars

This two storied white-washed building is popularly promoted as one of the oldest public houses in Belfast, generally accepted as having been established in 1720; the original proprietors from that early period up to the early 19th century are unknown. Nevertheless, it’s perfectly plausible that a tavern has been in continued existence on the same site at the premises known today as Kelly’s Cellars.

The map of 1715, designed by John Maclanachan, clearly shows the approximate position of several premises in ‘Crooked Lean’ and the two buildings at the bottom left row, whilst their purpose in undesignated on the map, clearly indicate the exact position of today’s Kelly’s Cellars bar.

The proprietor of Kelly Cellars at the early 20th century was Hugh Kelly. The 1819 Street Directory provides the address of ‘Hugh Kelly, Publican’, as 12 Berry Street and under the heading of ‘Belfast Taverns and Publicans’ he’s listed under the same address. In the Belfast Street Directory for 1841 the address is listed as ‘36 Bank Lane, Hugh Kelly & Co, Wine and Spirit Merchants.’ The Belfast Telegraph on April 14, 1961, announced that Kelly’s Cellars had been sold for £43,000.

The new owners were Messrs O’Kane, owners of the Glenshesk Inn at the corner of King Street and Castle Street. Bob Wilson was Manager of Kelly’s for 40 years up to 1961.

The United Irishmen

Historically the United Irishmen had various associations with Bank Lane, including that of the aforementioned William Tennent who lived there, and there were quite possibly connections with Kelly Cellar’s Bar as a meeting place for its members, but it remains historical speculation in the absence of official records or written memoirs of those perilous times.

It’s reputed that the United Irishmen’s leader, Henry Joy Mc Cracken, fled into Kelly’s Cellars and hid behind the bar to escape the pursuing yeomanry, successfully evading capture. Whilst possible, the recurring word in modern references is ‘reputed’ rather than ‘known’ to have occurred and the story is likely tempered with historical romanticism, but it contains a certain cultural and a romantic appeal as a great story with its association to the old bar for its patrons.

The Escape of William Kean

However, most famous of all is the well documented story of the incredibly audacious and heroic escape of the United Irishman William Kean through the Bank Lane subterranean sewer galleries. The Farset had been largely culverted over from Bank Street to the end of High Street by the mid-1780s. This beguiling tale of escape offers an alluring theory for the importance of Bank Lane and Kelly’s Cellars for the United Irishmen.

After the ’98 Rebellion the Donegal Arms Inn, located in today’s Castle Place, was taken over by the authorities for use as a prison for political prisoners. It was described in the memoirs of a contemporary as “crowded with officers and soldiers as well as the suspected and the doomed.” It was there that William Kean, friend and comrade of Henry Joy Mc Cracken, after participating in the Battle of Ballynahinch was imprisoned after his capture. He had previously been a staff member of the Northern Star, the United Irishmen’s newspaper in Belfast. He had been imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol along with Henry Joy McCracken and others and released in 1797.

The Town Sergeant, Dick Moore, was based there, and he was known for his sympathies for the plight of the prisoners and it’s suggested from recollections of a contemporary that he provided assistance in the famous escape of the condemned prisoner William Kean.

Kean had clearly prepared a well-designed escape plan. That night in his secured confinement he managed to climb through an open window at the rear side of the building, dropping down on to the roof of an adjoining house and making his escape crossing over several more roofs, finally scaling down into Hercules Street (today’s Royal Avenue). From there he crossed quickly in darkness into Bank Lane to carry out the next stage of his plan.

Part of the Belfast sewerage system through which William Kean made his daring escape in 1798

At the bottom of the street, opposite Kelly Cellars, he opened a hatch cover and gained access to the sewers and subterranean passages that spanned the length of Bank Lane, across into High Street with diversions to the vicinity of Cornmarket and Ann Street adjacent to the countless entries there. He likely had some form of bound oil rushes that when lit cast enough light and flickering shadows to help him proceed at pace through the sewer network, knowing this meant life or death, for he was within days of execution. One can only imagine those moments for Kean as he made his way along the darkened interior with the sounds of his footfalls on the stone footwell at the side of the sewer, echoing in the chamber with the sounds of rushing waters as he made his bid for freedom underground.

In the Ann Street/Corn Market vicinity he was able to emerge from the tunnels and enter one of the populated entries there, where it’s believed he was further assisted by Dick Moore’s family to affect his escape from Belfast, travelling by night by horseback across backroads and woods, sleeping in barns or forest camps to evade capture. Later the military search extended beyond Belfast and across Ireland after the Dublin authorities had been informed. Eventually, over time and with great tenacity, he reached Dublin to board a vessel where he successfully escaped to America.

The possibility that suggests itself from this event is that Kean was familiar with the entry and exit points of the Bank Lane and High Street sewers and the directions and interiors of the passageways. Is it possible that some of the United Irishmen had already been using the subterranean passageways as a means for communicating between meeting points, secreting themselves underground when necessary to travel to other rendezvous points at night in order to avoid detection by the authorities and their secret service agents? It seems inconceivable that he hadn’t prior detailed knowledge of these passageways before his escape.

Is it possible Kelly’s Cellars could have been a meeting place for the United Irishmen, entering, if necessary, the sewer tunnels as an effective means of concealing their movements to get back to Corn Market and High Street or to the ‘Four Corners’: North Street, Bridge Street, Waring Street, Rosemary Lane and Donegall Street, with their maze of entries and narrow courts where there were other established meeting-places?

Taverns of refuge

The Crown Tavern, located in Crown Entry off Ann Street, is reputed to have been the birthplace of the United Irish Society. It was there that its basic principles were believed to be discussed and agreed by the ‘secret committee’ in 1791 referred to by Wolf Tone. Other meeting places were Peggy Barclay’s Oyster House in Sugar House Entry between Waring Street and High Street. They met there under the guise of ‘The Muddler’s Club’. The Thatched House Tavern became the next meeting place when Peggy Barclay’s became too dangerous; it was located to the right of Sugar House Entry in Waring Street. There was another ‘thatched tavern’ in Frederick Street (Brewery Lane), also a meeting point for the United Irishmen. The home of United Irishman Thomas McCabe, known as the Vicinage and located in the grounds of what later became St Malachy’s College, Antrim Road, was a meeting place for its members, watched by the authorities and attacked by yeomanry in March 1793.

Bank Street in 1924 (courtesy of NI Historical Photographical Society)

Whilst speculative and without supportive documentary evidence, if there is a possibility of a real connection between the United Irishmen discreetly meeting at Kelly’s Cellars, at a safe distance from their usual meeting places, the truth may be found here – that the underground sewer galleries may have been used if necessary as an established communication network to move secretly around the town, evading the authorities in the darkened Belfast evenings to places where clandestine meetings were held in safety by its leaders without detection.

There is some additional anecdotal evidence to support this theory. John Smyth, writing in 1869 of his memories of Belfast during 1795 to 1810, related the story of Bank Lane, where Kean effected his escape, as being located “in this favoured locality”, i.e. favoured and well known to Kean and his comrades in the United Irishmen’s Association. There are other considerations. The British intelligence network in Belfast, Dublin and elsewhere was highly organised and had recruited a network of spies and informers to disrupt the United Irishmen’s organisation. They had been successful in planting a spy, Belle Martin, as an employee in Peggy Barclay’s Tavern in Belfast to spy on the leader’s movements there. They had also been regularly detecting and raiding meeting houses and carrying out arrests elsewhere. For example, in 1794 the Tailors; Hall in Back Lane in Prince’s Street, off High Street, was attacked by police, their meeting dispersed, members arrested and papers seized. They were precariousness times for the conspirator and revolutionary and they were under considerable pressure to avoid detection given their intentions and planning.

Whatever the merits of this proposition, Kelly’s’ Cellars retains the allure of history and mysteriousness – stories yet to be unearthed and revealed from its origins long ago.

In 1921 H.A. Mac Cartan wrote eloquently of this public house: “For this place is interesting not only by virtue of its chaotic and leisurely atmosphere, eloquent of comradeship and long quiet hours, but because of its human associations. Strip a few years away and you are in the midst of as jolly a set of impecunious optimists as Montmartre ever housed, poets, painters, playwrights, penny-a-liners and mere philosophers... Bohemians all, blown together by some lucky wind, scattered widely by an ill-natured breeze, to meet again, one hopes, when the tortured dream of life is over.”