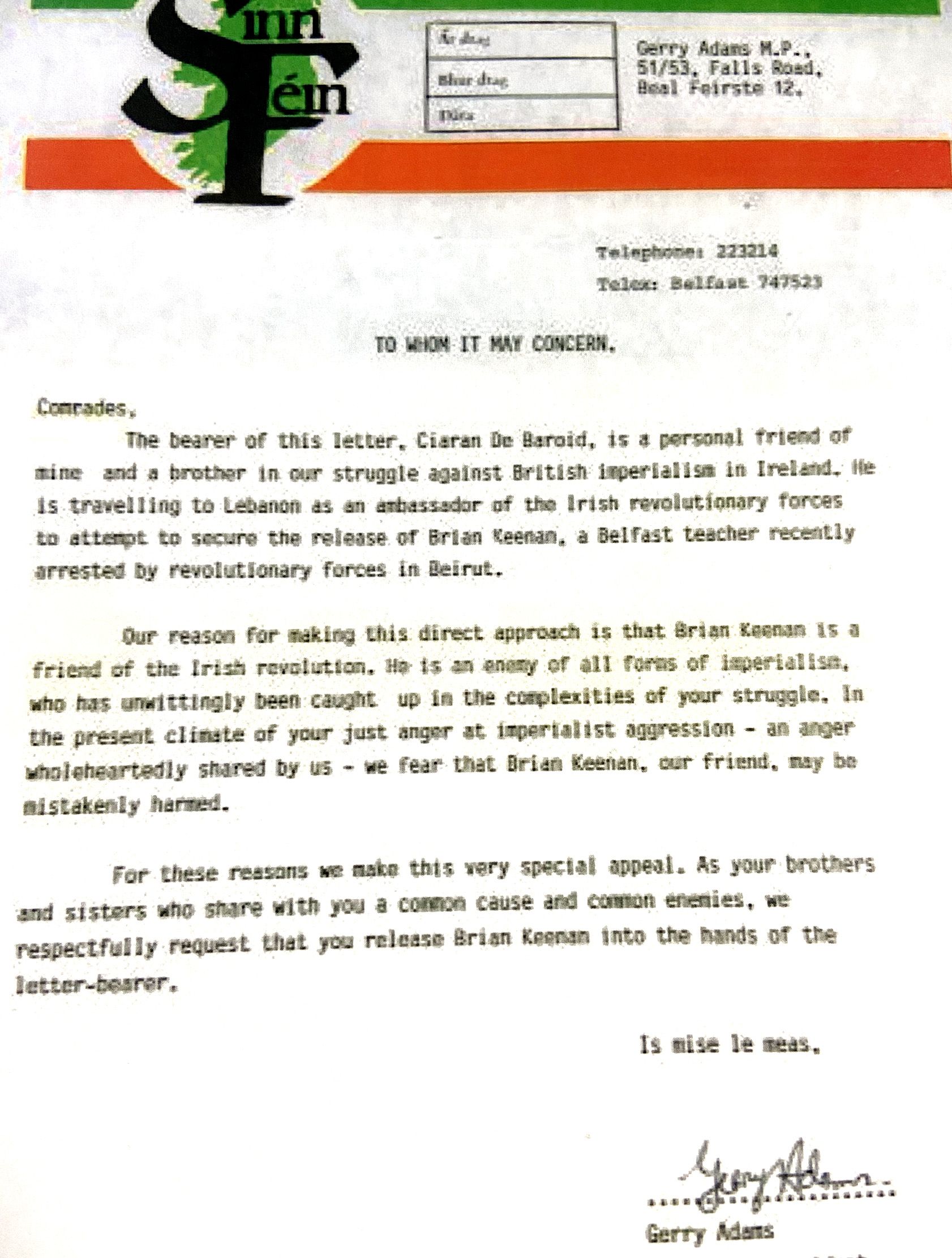

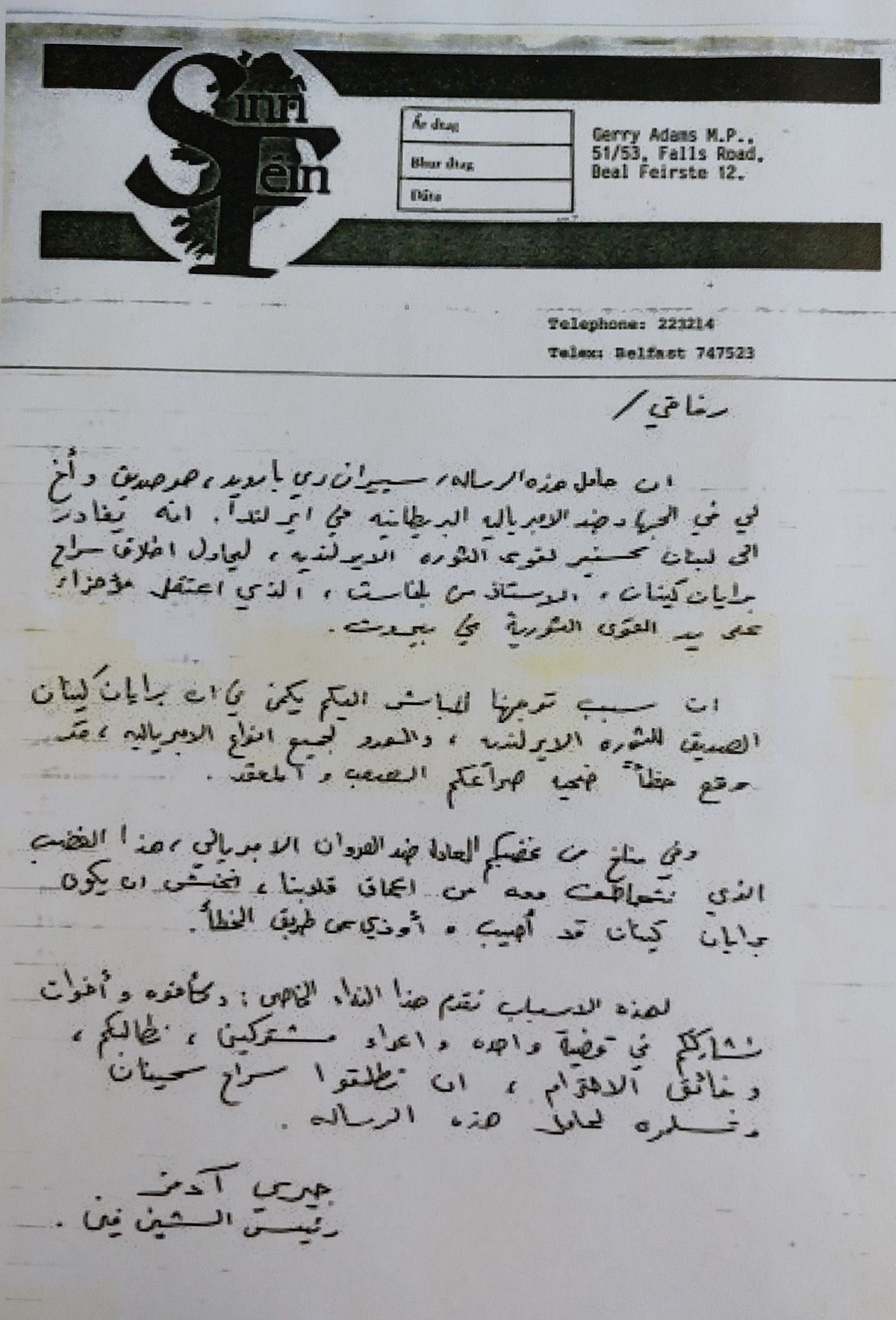

“The road from the airport through the southern suburbs of Beirut into the city centre ran through fundamentalist Hezbollah territory and was known the world over as ‘Kidnap Highway’. When Brian left the airport to head up that road he had, as his shield, an armed military escort. I had a letter from Gerry Adams”

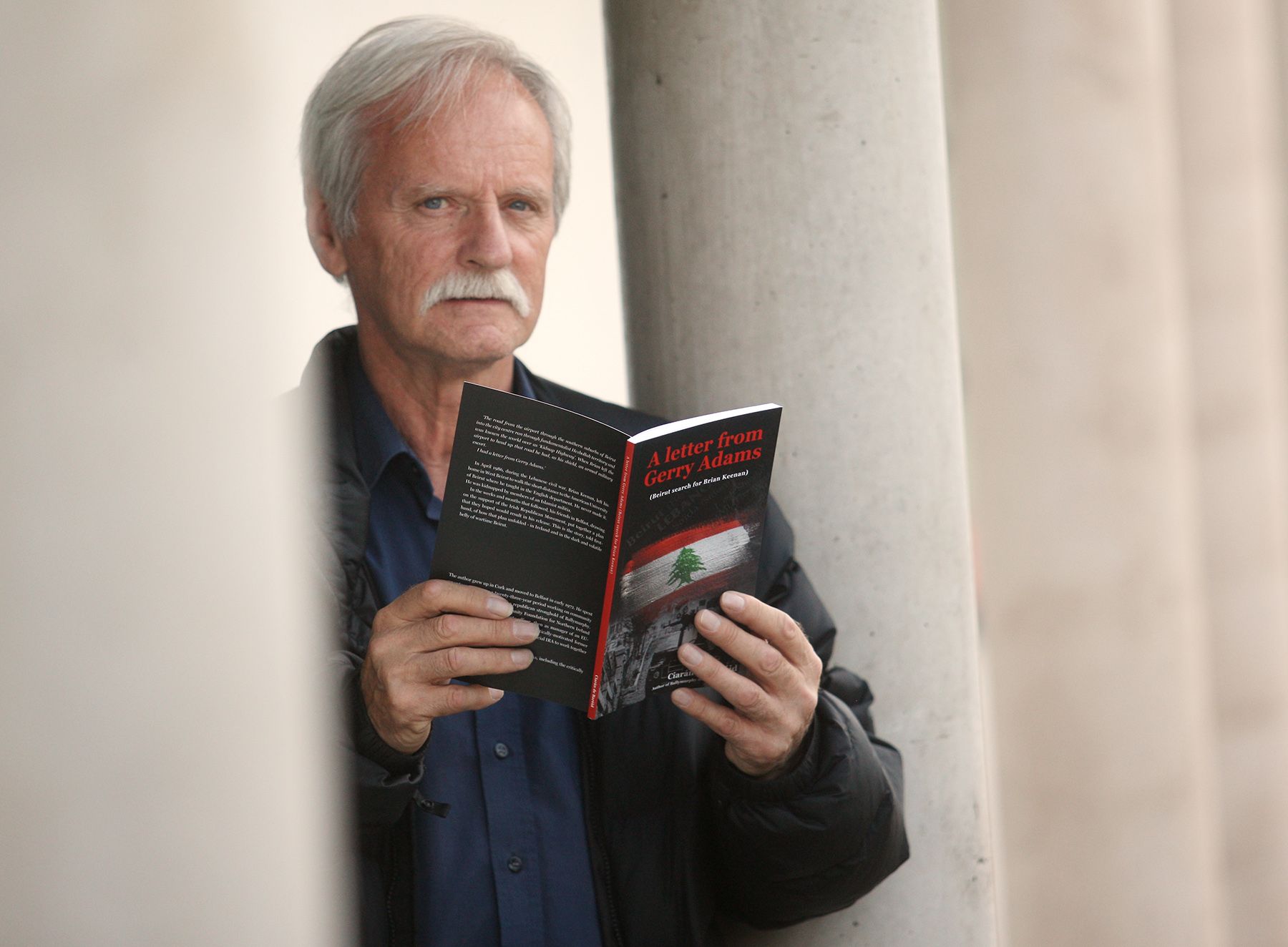

THIS stranger-than-fiction tale begins in the spring of 1986 when the author, noted Ballymurphy community worker Ciarán de Baróid, got word of the disappearance of his acquaintance, the east Belfast poet Brian Keenan, from the streets of Beirut where the latter had been teaching English in a local university.

The result for Ciarán was to be a whirlwind adventure over the next 12 months, as he found himself roaming the hazardous streets of Damascus and Beirut during one of the most lethal phases of the fifteen-year-long Lebanese Civil War. For Brian, on the other hand, it was just the beginning of a much longer and more troubled ordeal: his four-year-long captivity, in horrific conditions, as a hostage from April 1986 to August 1990. Keenan’s story has already been chronicled at first hand in the celebrated memoir ‘An Evil Cradling’, which he published upon his return to Ireland, while the story of Ciarán’s rescue attempt on the other hand only gets its first – deserved – telling in this small book.

The initial mystery over the identity of Keenan’s kidnappers meant that the first order of business for his concerned supporters in Belfast was to figure out who exactly had lifted him, and to appeal for his release on the (perhaps opportunistic) basis that Brian was both a neutral Irishman and socialist, who should not be made to bear the brunt of the anti-Western sentiment then riding high in the Middle East.

This day 30 years ago – 24 August 1990 – Brian Keenan was released after being held hostage in Lebanon for almost four and a half years.

— This Day in Irish History (@ThisDayIrish) August 24, 2020

His two sisters were flown to Damascus by the Irish government to meet him.

Keenan was met by Gerry Collins, Ireland's Foreign Minister. pic.twitter.com/E6inx0JJkb

As a result, they agreed that someone should travel to Beirut to seek out Keenan’s kidnappers. It was for this potentially suicidal humanitarian mission that Ciarán volunteered himself, much to the consternation of his long-suffering partner Cora, a domestic scene familiar to any reader of Ciarán’s previous books chronicling his exploits in Ballymurphy and abroad. The upshot was that in the summer of 1986 Ciarán landed in Damascus, where he endured a brief and ultimately fruitless trip as he sought and failed to negotiate government-sanctioned travel into neighbouring Lebanon.

Undeterred, the Corkman broke with both the conventions of international law and basic self-preservation by flying, several months later, directly into Beirut from Cyprus. Identifying Brian’s kidnappers, however, was no mean feat given the welter of militias, spies, standing armies and foreign military brigades that inhabited both West (nominally Muslim-leftist controlled) and East (nominally Christian-Phalangist controlled) Beirut at the time, not to mention the ever-shifting web of alliances and rivalries between the various factions which was the hallmark of the multi-faceted conflict. The sheer existential precarity of Ciarán’s quest is underlined by the fact that during the period of his visit dozens of Westerners in Beirut were assassinated or abducted by Islamist militants; some of those kidnapped were not as fortunate as Keenan, with several ultimately executed by their captors.

Luckily, our wily author does not go unarmed into the proverbial lion’s den, as he bears with him the titular ‘Letter from Gerry Adams’, which was, in fact, a sort of “information packet” prepared in collaboration with a range of individuals from the Republican Movement, including Adams, the family of Bobby Sands, and Jimmy Brown of the IRSP.

This collection of documents, translated into Arabic and customised for each identifiable militant group in West Beirut, vouchsafed both Ciarán’s personal anti-imperialist bonafides, as well as the anti-colonial heritage of Ireland, upon which basis an appeal was made for the liberation of Keenan.

Former Beirut hostage Brian Keenan, visited Magillgan Prison @NIPrisons recently to speak with prisoners about his experiences in the Middle East, and present some of them with creative writing awards.

— Justice NI (@Justice_NI) December 17, 2019

We asked him why he wanted to speak with the men, and his hopes for them. pic.twitter.com/ZrNu6zWGb9

As it was to later turn out, Keenan had in fact travelled with both his Irish and British passports, a point which complicated matters since his hostage-takers, Islamic Jihad, unversed in the nuances of ‘Northern Irish’ cultural identity, took this as a definitive sign that he was indeed a spy, and probably undermined much of Ciarán’s efforts to stress his Irishness.

Regardless, Ciarán’s Kafkesque experience traipsing between liaisons with militia leaders in fortified bunkers and compounds across West Beirut makes for wonderful reading, as various obstacles from the merely pedestrian to the distinctly life-threatening are negotiated. It is these surreal and darkly comical meetings with militia leaders – encompassing Druze, Shi’ite, Palestinian, leftist, and other factions – that are the highlight of the book, as the author comes face-to-face with some of the most powerful and dangerous men in Lebanon at the time. Some of these hair-raising experiences include a brawl in a disco filled with armed Druze militia members, and being caught in the middle of cross-fire between Palestinian militants and the Shi’ite Amal militia during the ‘War of the Camps’. In one shocking incident, the restaurant in Damascus in which the author has dinner is bombed immediately following his exit, killing scores of innocents. It’s horrific incidents like these that leave one taken aback by Ciarán’s sheer personal courage; or sheer fool-hardiness, as the reader may view it.

The closest thing to a direct acknowledgement of Keenan’s plight comes during a meeting with Sheikh Fadlallah, the spiritual leader of Hezbollah, who the author rightly feels could use his influence over the smaller Shi’ite organisations to secure his friend’s release. Alas, the cost demanded in return at this meeting – that the Republican Movement share its safe houses and collaborate in attacks with Hezbollah on targets within Europe – is well beyond Ciarán’s remit to guarantee. As a result, one can only shares his frustrations (and relief) as he boards his final flight home from Beirut in December of 1986, knowing that he had ultimately failed to rescue his friend.

While he may have failed in his one-man mission to liberate Brian Keenan (no more successful were Joe Austin or Denis Donaldson who tried again shortly after on behalf of Sinn Féin directly), he has by way of consolation given us this excellent book: it may not ascend to the literary heights of ‘An Evil Cradling” yet it packs plenty of entertainment into its 80 or so pages, serving at once as oral history and travelogue of a devastating conflict, as well as a time capsule of a bygone radical era, one in which Sinn Féin and the conflict in the North were located within a the context of global ‘anti-imperialist’ movements (or ‘international terrorism’ as Ronald Reagan more succinctly termed it), rather than the more prosaic international profile of today’s post-peace process environment.

A Letter from Gerry Adams By Ciarán de Baróid anceathrupoili.com £3.