THE Vice President for Research of Dublin City University, last week produced the first peer-reviewed paper on the true costs of Irish unification.

Based on research by the school of Law and Government at DCU and the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre, this is a significant intervention in the constitutional discussion. Professor John Doyle was at the forefront of questioning the assumptions of last year’s report by the Institute of International and European Affairs' John Fizgerald and Edgar Morgenroth, which made a huge splash when they said that unity would cost €20 billion over 20 years. At the time Doyle and Professor Seamus McGuinness dug into the figures and questioned the underlying assumptions. Fast forward to this year, and Professor Doyle has put an alternative number on it and it’s under €3 billion for about 10 years. Some difference.

What makes this paper different is that it is peer-reviewed and holds academic water. In that respect, it raises the bar for future economic presumptions underlying the prospective cost of constitutional change.

Alongside this impressive academic rigour, John Doyle has a knack of making things relevant to lived lives. Not being an economist is no barrier to engaging with his arguments about the detrimental impacts of the 11-plus/academic selection process on the economy. Or the impact of failing health systems and how a person in the south can book a GP from an app on their phone and get seen in 24 hours, whether they pay or don’t.

In this paper he creates an accessible, credible and compelling argument which informs the debate.

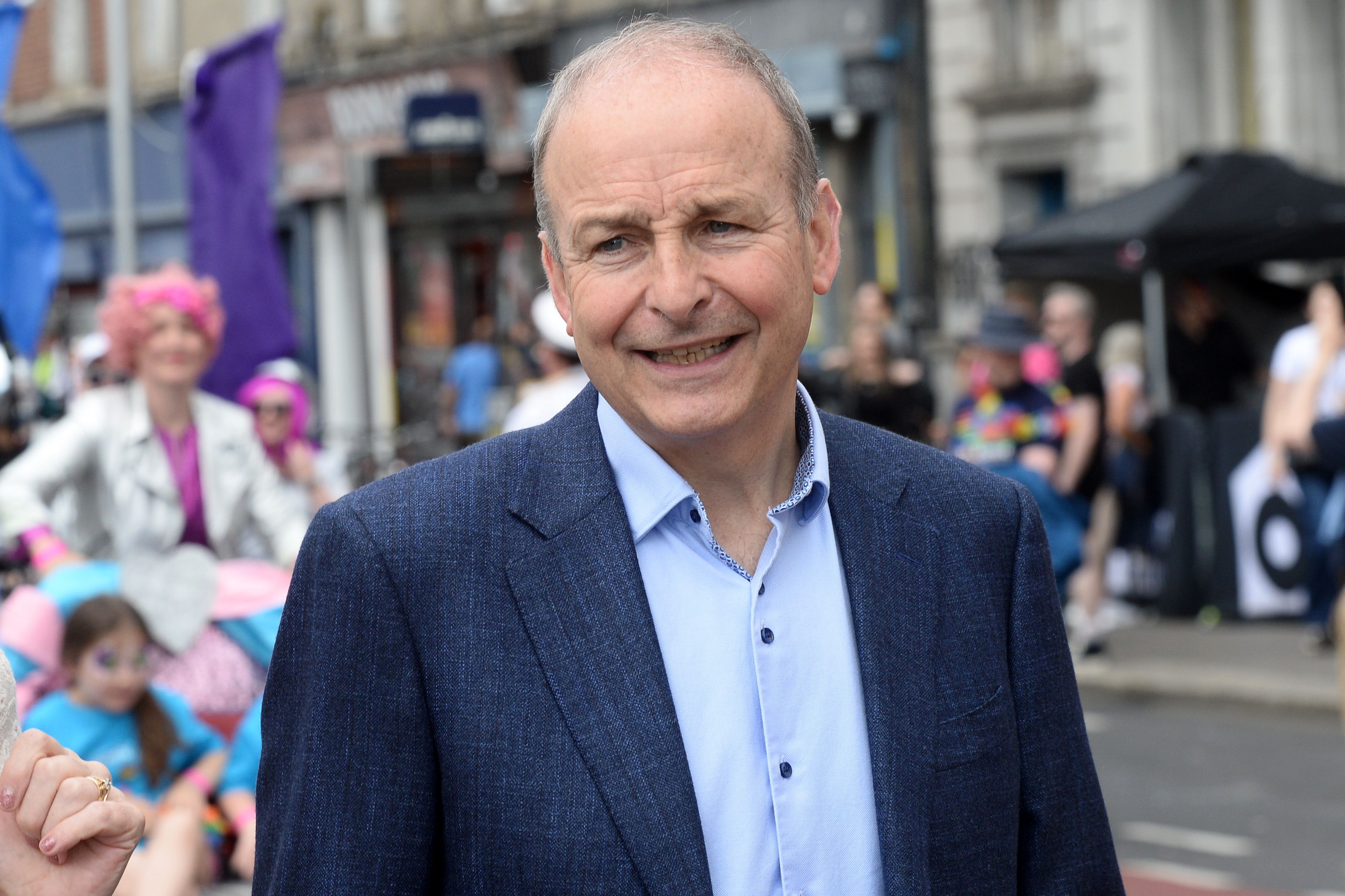

Sadly, An Taoiseach is missing a trick not engaging with this. Mícheál Martin is focused on relationships and reconciliation. His focus is, God knows, no bad thing. We of course need to ensure we build better and lasting friendships. But we can, constitutionally speaking, walk and chew gum. All of the data is pointing to a constitutional referendum being held on this island in the near future. Our population needs that referendum to be held in an environment of clear and accessible information so we can make informed choices.

At the top of the list will be questions like: Can we afford it? Will my children be better off in their lifetime by making this choice? Would our future be better together than our partitioned past?

Surely by engaging in research on those questions we engage in processes of reconciliation too. We need to understand each other’s economic conditions not through the prism of sectarian or self-serving myths, but by honest explanation and hard listening. Surely that conversation will mean that we will find spaces where our common interests will trump our divided presumptions?

There is no-one open to persuasion on the constitutional future who wants to be encouraged by a fool’s promise. A United/New Ireland will be no utopia. But an honest engagement where we agree to build a respectful future, based on law and common interest in shared prosperity, might be an attractive place to start.

Maybe An Taoiseach might consider that our partitioned past and present is the place where reconciliation has failed. The prospect of unity is where future reconciliation is possible. The process of debate will in itself lead to better relationships. Every serious contribution to an informed choice is a valuable contribution to prospective reconciliation. And not to be dismissed.