LAST week we remembered Frank Stagg, who died on hunger strike in an English prison in February 1976.

Frank began his fourth and final hunger strike in December 1975. He died 62 days later. He last request was “to be buried next to my republican colleagues and my comrade, Michael Gaughan”. Michael died on hunger strike two years earlier and had been buried in Ballina with republican honours.

Faced with the prospect of another high-profile funeral of a republican hunger striker, the plane carrying Frank Stagg’s coffin was diverted by the Irish government from Dublin, where the Stagg family and friends were waiting, to Shannon. Frank’s body was hijacked and taken by helicopter to Ballina, where it was buried. A 24-hour guard was put in place and concrete was poured over it to prevent the family from exhuming the coffin.

Frank’s brother George later described how, when he took his mother to visit the grave, Special Branch officers took photographs of her as she knelt and prayed.

PROMISE KEPT: Frank Stagg was eventually buried with military honours

Recently, George explained to me what happened afterwards for a new book I am working on. The caretaker of the cemetery was Gerry Ginty, who was a Sinn Féin councillor. His mother, Jane, also worked there, selling lots and burial plots. George asked her one day: “Who bought that grave that Frank is in, who paid for it?”

Gerry said nobody. George asked if he could buy it. He took out his cheque book to pay three pounds.

“How much are you going to give me?” said Jane. “Three pounds,” George replied.

“No,” she said. “Give me a fiver. For a fiver you can get ‘a double’. That grave and the one next to it.”

“Why?” George asked.

And she said, “In case you ever have to dig down.”

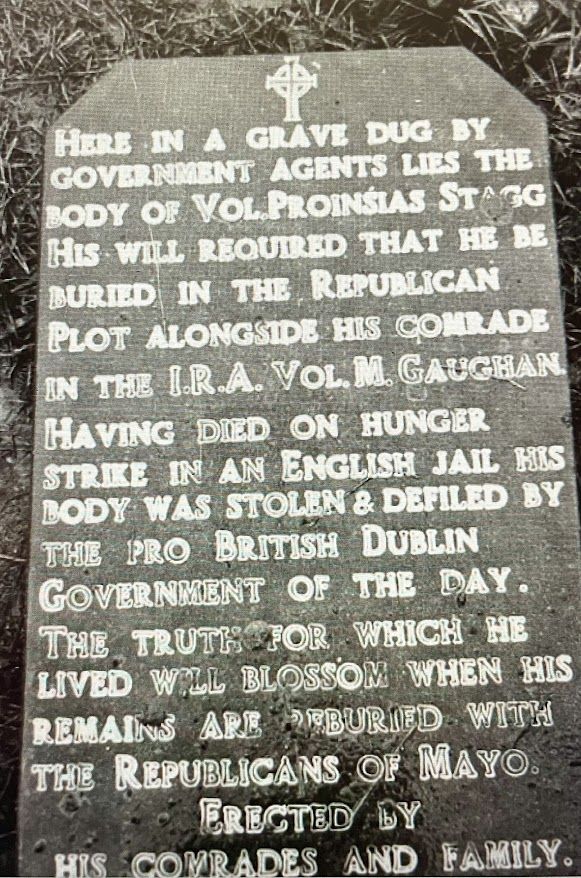

So George bought both graves. He got a headstone erected on the empty plot which read: ‘Here in a grave dug by government agents lies the body of Vol. Proinsias Stagg. His will required that he be buried in the Republican Plot alongside his comrade in the IRA Vol. M. Gaughan. Having died on hunger strike in an English jail his body was stolen and defiled by the pro-British Dublin government of the day. The truth for which he lived will blossom when his remains are reburied with the Republicans of Mayo. Erected by his Comrades and family.’

The Special Branch maintained a round-the-clock watch on Frank’s grave. But after about a year they realised that it was a waste of Garda time and resources.

That summer, 1977, George got a call from Gerry Ginty, who had already been hatching a plan for the removal of Frank remains.

He said, “We can do this!”

They didn’t know if the concrete went down the sides of the grave also, entombing the coffin and making it virtually impossible to break into the grave from the side without using machinery, which would attract attention. They reckoned they needed six trustworthy people in total for the operation.

Gerry and George made two. Gerry got one other, Con Ryan, and George got the other three – his brother-in-law Jimmy Doyle, Sean Comiskey from Trim and Paul Stanley from Kildare.

Gerry chose the night carefully, November 5th, 1977, a night when there was no moon. It was very dark and a bitterly cold night, with continuous driving rain. They had two lookouts – one up the town, and the other down at the gates of the graveyard.

Four of them would carry out the digging – two on, two off. They made good progress but were soon soaked through to the skin. There was hardly anyone out and about, but at one stage the blue light of a Garda patrol car was flashing down near the gates and they thought they had been spotted. They later learned that the driver stopped to offer a lift to a rain-drenched pedestrian. Once or twice headlights from cars leaving a nearby house swept across the cemetery and forced them to duck.

George goes on to describe how when they had dug about four foot down they came upon a massive rock. It was about five feet in diameter. It must have weighed about a quarter of a ton, George thought. They were perplexed: this is it, they not going to be able to get this huge boulder out George explained. But Gerry told them to keep trying. They sent for the lookout to give a hand.

Two men were down in the hole and they got a rope around the big stone and rolled it up the bank, inch by inch. It was a miracle. After they removed it they stopped digging down and began to dig sidewise into Frank’s grave. Then they discovered there was no concrete down the sides.

It wasn’t long afterwards that they struck the wood of the coffin. Thankfully it was in fairly good shape. They had quite a bit of trouble getting it to move because it was stuck there by suction. But, again, George explains, Gerry was very clever. He just dug little holes over the coffin and to the back of it, until they were able to put the ropes through and gently move it outwards.

George felt very proud. He was fulfilling a great sense of duty. He was very mindful of the words he said to the Garda superintendent at Shannon airport when Frank’s coffin was seized on behalf of the state: “I’m telling you now, I promise you. A day will come and I’ll have him back.”

That day had come. When his friends and comrades eased Frank’s coffin out of its resting place and brought it to the surface George placed his hands on his brother’s coffin and he whispered: “For you, Frank. We’re doing this for you, Frank.”

They placed the coffin on a sheet of plywood, in case it would disintegrate while being moved. They carried it down to the Republican Plot and within a short time they had Frank’s remains reinterred beside his comrade Michael Gaughan. They said a prayer. Then, standing beside the grave of the two republican heroes, they saluted. It was not yet dawn.

They left the graveyard and each went his own way. George got in this car and headed back home.

Later, he rang his mother to tell her it was done. He asked her to listen out for the news. She cried. And she thanked him.

Partitionist RTÉ need rugby-tackled

IT’S funny the things that annoy me. With everything else that’s happening in the world I do consider myself very lucky. So I try to put wee things which irritate me into perspective. All things are relative, I tell myself.

As you might expect, and as regular readers will know, I get really annoyed, like many other people, at the way the people of Palestine are treated. Or Donald Trump’s utterances – and actions. Other global issues upset me. For example, human indifference to climate change – especially among those who cause the dangers to the environment.

Litter annoys me. But a few Sundays ago when I tuned into RTÉ to watch the Rugby match I was reminded of one of my pet hates:’ The RTÉ notice which advises viewers who live in the North that This Programme Is Not Available.’ I usually came across it when I was trying to tune in for Gaelic games coverage. That seems to have improved following a vigorous Fair Play For Gaels campaign. It’s still not as good as it should be, but well done to all involved.

However, when I turned to RTÉ for the rugby and to get the benefit of Irish commentators there was no fair play for Ireland rugby fans in our house. Just the Verboten graphic. Why? Why did I have to turn to BBC to watch us beating Scotland?

Funnily enough, someone told me that The Young Offenders was also out of bounds for Nordies. So I checked that out. And yes, it’s true. This programme – about Cork langers – ‘Is Not Available’ either. And don’t get me started about the weather maps, RTÉ Radio’s Morning Ireland traffic updates or Late Late Show competitions. All cut off at the border.

In this era of global communications it’s long past the time that RTÉ dropped its partitionist broadcasting.