AS ever on Remembrance Sunday, the hour was approaching when I should have rise. from my desk and join the rest of the UK in a minute’s silence. Should have.

Remembrance Day is when British people commemorate/ honour the contribution of British and Commonwealth servicemen and women in the two World Wars and other conflicts. People wear blood-red poppies as a symbol of their commitment to Remembrance Sunday.

When you commemorate someone, you recall and respect them. And thank them. In London on Remembrance Sunday there was a two-minute silence at the Whitehall Cenotaph, followed by The Nation’s Thank You Procession.

So what conflicts does this remembering and respecting and thanking mark? Well, World War One, World War Two and any other conflicts in which the British armed forces were engaged in the last century, this century, and as far back as you care to go.

During World War One, British armed forces executed 305 of their own soldiers because they were judged to have deserted or displayed cowardice. Ten years before the outbreak of World War One, in 1904, British armed forces killed hundreds of Tibetans. They used machine guns, in what is remembered (certainly in Tibet) as the Chumik Shenko massacre.

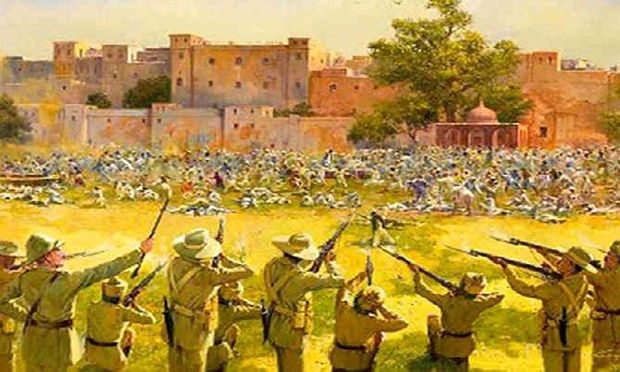

In Jallianwala Bagh/ Amritsar, British troops in 1919 fired into a crowd and over 1,000 Indians were killed. Reginald Dyer, who ordered the killing, was feted in Britain as a hero, and given what would be £1 million in today’s money. That event is known as the Amritsar Massacre. Two days after that massacre, the RAF were sent to bomb and machine-gun protestors in Gujranwala. More than a dozen people were killed. That is known as the Shaji massacre.

In 1925, in China, 52 worker and student demonstrators were fired on and killed in Guangzhou. By – yep – British armed forces.

And then we had the First World War itself (‘The war to end wars’), an ocean of blood-letting in the cause of... what? Small nations? Freedom? Civilisation? I think not. Thousands of young Irishmen sacrificed their lives for the lie that after the war, Ireland would be granted Home Rule.

None of this is to deny the British people the right to commemorate their war dead. The great majority of countries do that. But it would be to fly in the face of history to act as though the British Empire and its armed forces had always acted honourably.

Physical degradation of the native people in Kenya, to take one instance, was appalling. Concentration camps were established, native people rounded up, and over a million of them suffered physical and/or sexual abuse. In India, the native people of Bengal were forced by the conquering British to work day and night to survive. Many didn’t: it’s reckoned that over two centuries, twelve famines occurred there and some sixty million people may have died. Which makes even An Gorta Mór seem small.

None of this suffering would have been possible without the might of British armed forces. The British Empire, which laid claim to other people’s land all over the globe, couldn’t have come into being without the British armed forces.

So to ask the people of Chumik Shenko or Amritsar or Gujranwala or Guangzhou or Kenya to commemorate the British armed forces would be like... Well, like asking Irish people to commemorate the Black and Tans or the Parachute Regiment or other British regiments which over the centuries shed Irish blood.

When the First World War began in 1914, Britain was an empire. In his novel Burmese Days, George Orwell has one of his characters explain what colonialism involves: It means coming to other countries, killing people and stealing their stuff, he says. On a massive scale, that’s what Britain did in North America, in Australia, in India, in New Zealand, and across the globe. And to borrow a phrase, the cutting edge that made the seizure of these places possible was the British armed forces.

So no, you won’t see me observing the two-minute silence and you won’t see me wearing a poppy. Except it’s a white one, maybe, and says in large letters “MIGHT IS NOT RIGHT.”