St Thomas’ Secondary Intermediate School was opened in September 1957. In April of that year, I remember the muscular caretaker, a local man, showing me around the empty, gleaming gymnasium and the new-smelling, loud tiled corridors. All the sounds of walking through an empty school that has no thumbprints feel oddly spooky.

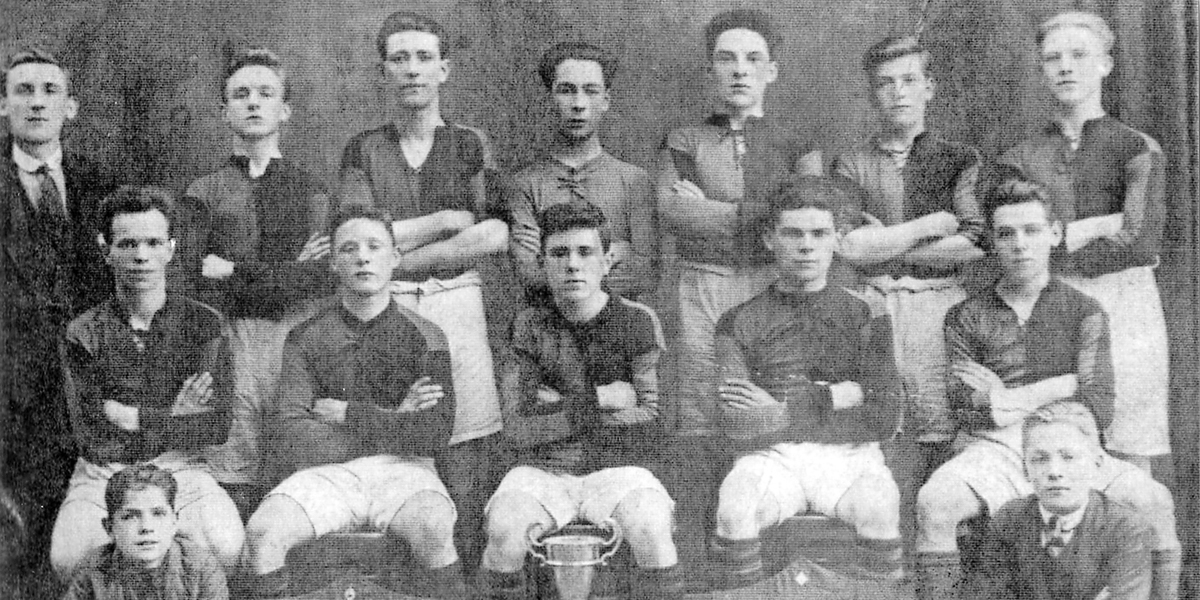

A cement mixer was chugging and the weak, slanting sun threw shadows across two men stepping through a mound of gravel. One of the men was the in-coming headmaster of the school. Mr Michael McLaverty was a short story writer and novelist who, according to my father, had been a “plucky” footballer when he was young. I sense he was shy, urbane and intelligent. I was eleven years of age and my interest was unfussy. In a few month I would leave St Kevin’s Public Elementary Primary School, the steps with iron balls for grips and the laurel bushes I ate my lunch among.

I had no feeling then of great occasion or presence. The summer was spent playing football or walking around the sodden floor of the forest in Ballycastle, or fishing off the pier, trying too to imagine how cold it was further out at sea. Were there golden eagles at Fair Head? Who was the Grey Man after whom Grey Man’s Pass got its name?

These abstractions about places dominated a growing consciousness with romantic and adventurous possibilities. There was, after all, the feeling that summer was a series of rhythms winding down the long and dappled road to Belfast.

At that time, I would have been familiar with the Black Mountain, the place where the snowdrifts were deepest, the limestone crevices dangerous and the cool hiding places among the fern beds. Around all that was ‘the Game’, with its springy grass and tough, shiny heather, the curlews and the sparrowhawks which lived in the strange tangle of sparse land and leaning fences, sporting beards of sheep wool. A man, a faceless man, they said, patrolled it in some vagrant and loose way. The feel of the place was rural – the pace unhurried; television was black and white.

In this context, the years I spent at St Thomas’ were robust but easy-going too. Mr McLaverty would remind us every now and then to appreciate this natural beauty, work hard and “Never think about Saturday.”

The boys turned out for their first assembly with black blazers, wearing the school crest, and grey flannel trousers. The pleasant smell of Cherry Blossom shoe polish and Lifebuoy toilet soap wafted through the air. Michael McLaverty took assembly prayers: the Anima Christi, St Patrick’s Breastplate and the Prayer to the Holy Spirit. Classes then lined up and teaching began.

I had little contact with Mr McLaverty in the early years. When GCE examinations began to loom in Fourth Year, there was more of an avid interest in the literature and poems set in the University of London syllabus. Apart from a few short pieces of his own work, I can’t recall much prose: The Red Pony, John Steinbeck, a novella; and general conversations about Joseph Conrad’s The Nigger of Narcissus, the famous line – the only line in Nostromo given to the Belfast man: “Get stuck into him!”

The main concentration was on the new poems in A Pageant of English Verse: Thomas Hardy’s Afterwards, Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Pied Beauty and The Wreck of the Deutschland, The Windhover and Edward Thomas’ Adlestrop. He loved all of these poems, The Wild Swans at Coole and The Song of Wandering Aengus by WB Yeats. He knew them all and recited them at will. I heard him recite Edward Thomas’ poem, Tall Nettles, in the University Bookshop a year or so before he died in 1992.

These poems sustained and invigorated McLaverty when he needed his head showered from the profound monotony of administration. On bright mornings I can still hear his voice trailing over WB Yeats.

Lover by lover, they paddle the cold

Companionable stream or climb the air

Their hearts have not grown old.

The emphasis on the fidelity of the swans was the key to McLaverty the man. Fidelity in all things. Over and over again he explained the precise word, the need for feeling in the poetry. There would be no Sons And Lovers without feeling – the reading public would know it was fraudulent. The preachments were gentle but firm, reasonableness in all things.

One of his other great passions was geometry. Isosceles triangles and the Theorem of Pythagoras accompanied a large wooden compass on the blackboard. The chalk squeaked.

Later, I would sit at a desk eight storeys up, overlooking Soho Square, the Ministry of Transport. In the metropolitan winters, in bland tube stations, he was a lodger whose interests had come to stay. A lot of my time was spent between the bookshops at Tottenham Court Road and Charing Cross at lunchtimes.

In reflection and a thousand conversations, the smoky scribbles of Belfast streets came back; the scandal giving, the nuns and priests, the exact detail, the small farmers, and women he scrupulously committed to language.

Suffering was included in his vision of things, and WH Austen’s poem typifies this:

The mass of majority of the word; all

that carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help.

Across the years the critics have been laudatory to Michael McLaverty – Walter Allen, Edwin Muir, Seán Ó Faoláin and many others knew the accumulated power of his Chekhovian eye for detail, his psychological realism, his authentic dialogue, his spare and sparse sentences, the well chosen word.

I have heard that shortly after Call My Brother Back was published in 1939, McLaverty got an offer from Hollywood for a screenplay. He wouldn’t alter a dot or comma, he wanted no playing to the gallery.

All the stories have earned their spurs, so to speak. Some were published in The New Yorker years ago. The Road To The Shore was dedicated to Robert Greacen, John Boyd and Roy McFadden. Greacen remembers him as a “good man”.

Stories like The Prophet depict the innocence of an earlier time and of the serene but lonely island of Rathlin. Pigeons is a Belfast story and I think it is the one which resonates with the old Beechmount of the 1940s. The Game-Cock is set around Toomebridge; those practices are now illegal. Steeplejacks seems to be the most industrialised of the stories and, once again, the dialogue, sense of occasion, the awe-struck youngster and the steady detail are manifestly clear-eyed. “Jackie pulled at a loose thread on his jersey.” These sentences are inserted effortlessly into the narrative.

In all of the stories, a patient watcher is evoked again and again. A half-crown which has fallen behind the sofa again gets down to brass tacks, of life and chance.

The BBC has in its archives the short films made and produced in the 1980s of Aunt Suzanne and The Schooner, which again show the humourous side of McLaverty’s sensibility. On the question of sexuality, he felt he had no need to state the obvious. He hadn’t come up the Lagan in a bubble. He would have had a moral reticence about it for fear of morally tainting the reader.

He chose Steinbeck’s The Red Pony for us because it had a purity about it that had nothing to do with adult concerns. The vision in it was pre-pubescent. McLaverty had that pre-pubescent sense of vision and instinct. That is where he worked from.

Writers as diverse as Walter Allen and Edwin Muir rated him highly. Ethel Mannin too. McLaverty was not effusive, he preferred the quiet pastoral life of County Down. I suspect he was hurt by the sad repetition of the Troubles, as he had seen the Twenties and Thirties – “the dirty old glove”, as Heaney refers to it. Understatement and silence are his preferred habitat.

It was about 1962 that he gave Seamus Heaney the advice in the poem Fosterage, Royal Avenue, 1962; the caution about overstatement.

While on teaching practice, Seamus Heaney came to St Thomas’ about October that year. I remember him, his voice grave and resonant, his big, brown shoes, reading from Carrickfergus by Louis MacNeice. He was an enormously decent man with extraordinary antennae. About that time, too, John Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize. On the question of artistic confidence and acclaim, it is interesting to note that in that in a letter to his agent, he said: “I am scared to death of popularity. It has ruined everybody I know.”

It was a year of confluences, the Cuban missile crisis. It was also my last year as a schoolboy. I had seen or heard nothing of McLaverty during the 1960s and most of the 1970s, when he came to St Dominic’s High School to take sixth formers, last period in the morning, for the Irish short story. My last sight of him was about 1990 on the Ormeau Road. “This is a desperate town,” he said, “but you have to content yourself wherever you are.”

He was like St Paul, with his own version of “unhappy and at home”.

The gifts of people live on after them. When I am walking through the last of the sooty streets, or see bread vans in the frosty mornings and smell Veda bread, or see pigeons on the roofs, I know all of these are embedded in me like a psychic watermark. I am more aware of them because Michael McLaverty taught me. He lived an honourable life and the evidence of his value is contained in the libraries and bookshops of the world.

By Brendan Hamill

First published in Fortnight.