Not so long ago most families had a couple of books that took pride of place in the living room – there would almost certainly be a Bible and maybe a dictionary or an encyclopaedia, in our case the free first one of a collection too dear to buy.

But who needs a reference book today when everything you need to know is available at the swipe of a phone?

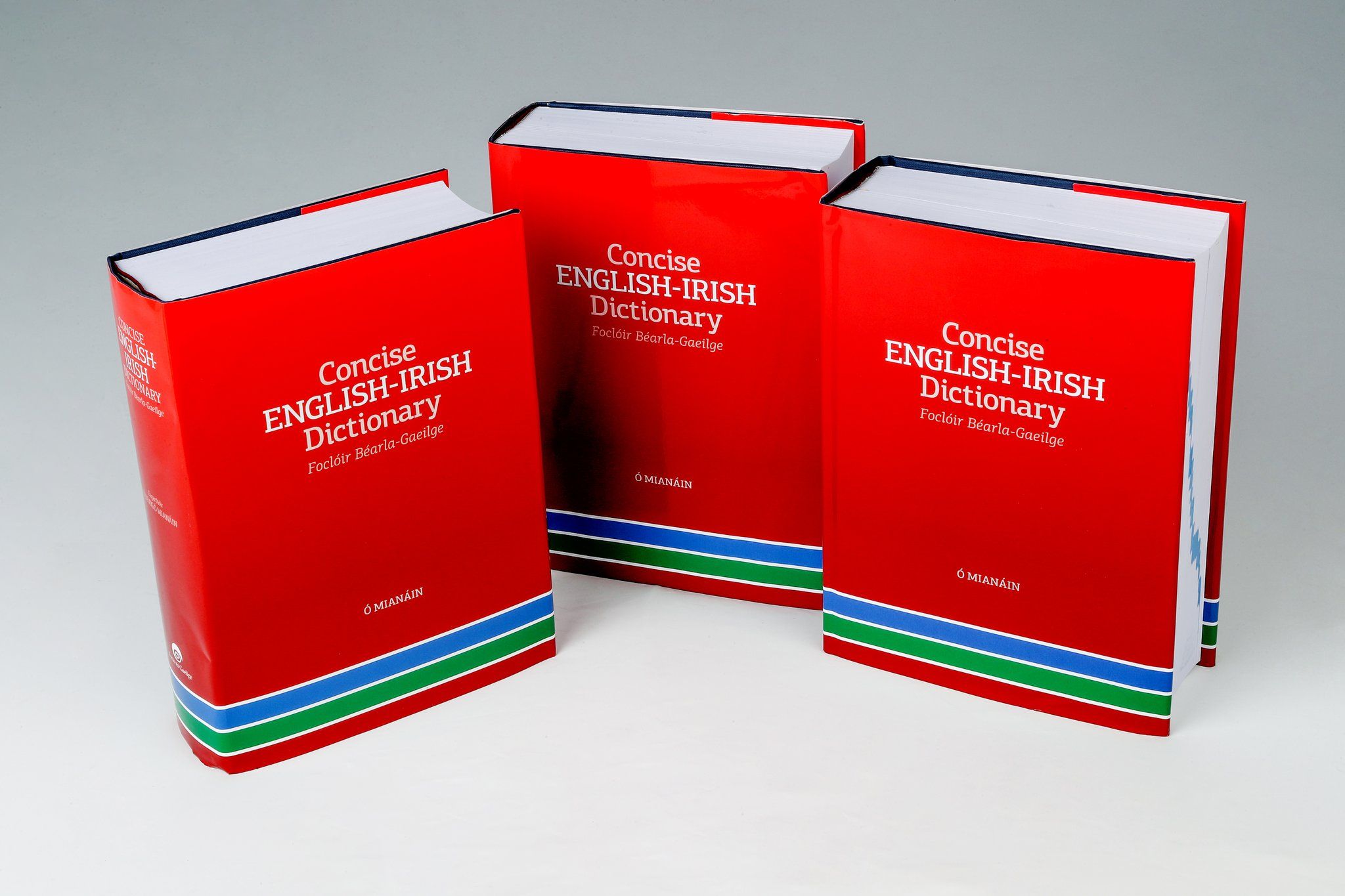

However, a groundbreaking book published this month is winding back the clock. The Concise English-Irish Dictionary is the first for 60 years and it’s enjoying incredible sales already.

It’s a magnificent book that deserves to take pride of place in every Irish home – and a Belfast Irish speaker was right at the heart of it.

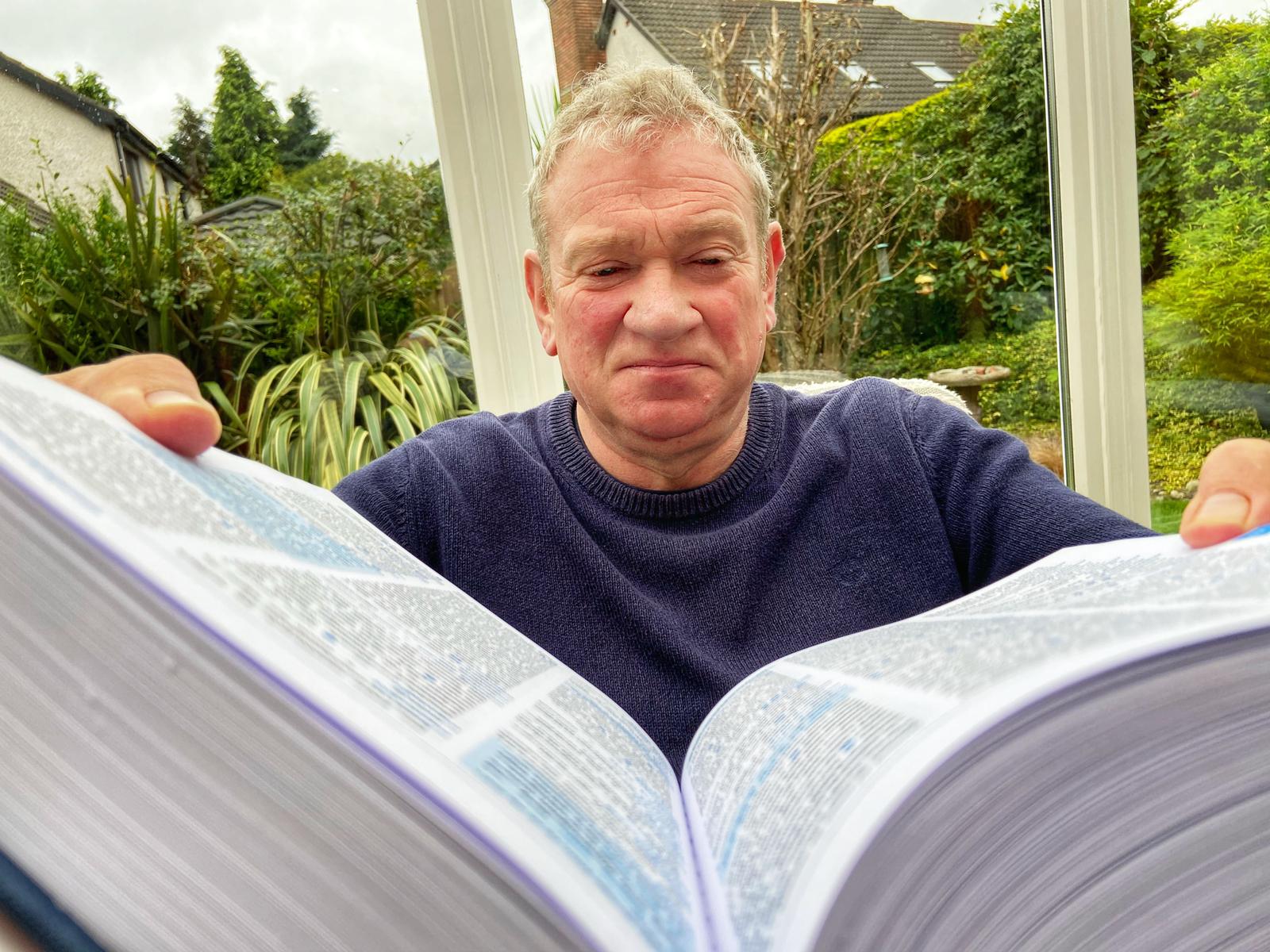

Translator and lexicographer Pól Mac Fheilimidh was one of a small team of language experts working under editor, Derry’s Pádraig Ó Mianáin.

“I started working on it part time in 2009 - I had to pass a test at first and there were around six of us working on it from all around the country at any one time. Usually Ulster Irish is left in the halfpenny place compared to the two other dialects, but thankfully we were well represented on the team!” he told belfastmedia.com this week.

TOGHA AGUS ROGHA: The new Irish dictionary

Pól was sent ‘batches’ of English words to translate and rather than working alphabetically from A to Z, the words were prioritised on how often they are used in Ireland.

“There’s an in-joke with lexicographers - ‘have you got past aardvark yet’ because that’s the first word in the English dictionary. But that’s not how we worked. Old dictionaries you might have in the house have loads of words that are no longer used, so we looked at newspapers for example and drew up a list based on how often they are used today,” Pól said.

Editor Pádraig Ó Mianáin said that in all languages, the 1,000 most common words make up 80 per cent of the spoken language, so translating those was the first step. He added: “I’d say that about half of what’s in de Baldraithe [the last English-Irish dictionary published in 1959] is not in our book because life has changed that much.”

He said a great example of how language is constantly changing is the new words that we are now using since the coronavirus lockdown. “The book was at the publishers in Italy but we still managed to get some of the new terms in, like social distancing – scaradh sóisialta – and cocooning.

“You could say the book is already out of date after a couple of weeks, and that’s where the internet version of the dictionary, focloir.ie, has the advantage, because it can be continually updated.”

Pól, who used to head up the schools publishing unit Áisionad in St Mary’s University College, said it was important that the richness of Irish was reflected in the translations.

“For example we wanted to use as many proverbs as possible, and also to give an insight into modern-day Irish and how it’s spoken.

“Some words were easy to translate - bitumen for example. It’s not used in any other way or phrases. Or technical words like mainframe. Then you have more common words with a couple of meanings - take ladder, it sounds simple but then you have someone making their way up the promotion ladder or getting on the housing ladder.

“Then you get to the verbs like go, see, come, and they are very complicated. ‘The word ‘get’ runs for eight full pages! It’s the type of word that’s used all the time, especially in Belfast - we don’t even realise how often we use it.

“But my favourite word must have been ‘set’,” said Pól. “I wasn’t expecting it to have so many meanings and to be used so much. It really is an essential wee word in the English language.”

The team made a conscious effort to reflect English as spoken in Ireland, including slang words. ‘He was very fond of the gargle’ - bhí an-dúil san ól aige – is just one cracker included. More controversially, they’ve given the official blessing to some words and phrases recently borrowed from English – to throw in the towel is literally ‘an tuáille a chaitheamh isteach’, while ‘leaindeáil’ is okay for to land, say, a plane. They point out that it’s remarkable that a word like leaindeáil is only now appearing in a dictionary as it’s been in common use for at least a hundred years.

Ulster Irish speakers might be disappointed there’s no madadh – dog – in the dictionary – instead it’s spelt madra – the standard form. However, when a word has different meanings in different dialects, it’s included – for example gasúr means boy in Ulster Irish, but a child of any gender in Connacht.

The 80 pages of essential language and grammar notes at the back highlights the danger of what Irish speakers call Béarlachas, where English idioms are translated word for word. One simple example is when Irish speakers might say ‘rinne mé mo leaba’ for I made my bed, when the correct traditional way is ‘chóirigh mé mo leaba’.

And the authors say that this dictionary will finally do away with the “tiresome refrain that Irish has Irish has no words to describe sex” - indeed Pól adds that “the f-word, b-word and c-word are all there”.

“We didn’t want to hide anything but at the same time not to go overboard with them. So we have foc, focáil agus focáilte there - there’re not native Irish words, but there’s no hiding the fact that they are widely used.”

Pól says he’s delighted that it will be known as Ó Mianáin’s dictionary in recognition of the “amazing” effort Pádraig put into the project. Such is the central role of dictionaries in Irish speakers’ lives that the authors of previous works like Dinneen, de Bhaldraithe and Ó Dónaill are still household names. To that pantheon of greats we can now add Ó Mianáin.

Pádraig recognised that its publication was a milestone in the history of the language and said the book was comparable in quality to any dictionary in any language.

“It also shows that the Irish language can deal with modern-day life,” he added.

The 1,800-page Concise English-Irish Dictionary was subsidised by taxpayers on both sides of the border and at just £25 (€30), it’s a fraction of what a dictionary like this should cost. Since its launch two weeks ago the bookshop at the Cultúrlann on Falls Road had sold 150 copies and is struggling to keep up with demand. The 8,000-copy first print may well be sold out as it will make a popular Christmas gift.

By the way, the free encyclopedia in our house was about everything starting with A – we never did buy the other 25, each for a letter of the alphabet. But still, at least we knew about the Aztecs, Angola and Azerbaijan. And how to Appreciate a brilliant book like Ó Mianáin’s Concise English-Irish Dictionary.