For veteran reporter Bojan Brezigar reporting from Belfast on vying constitutional claims over the North of Ireland is a bit of a busman's holiday.

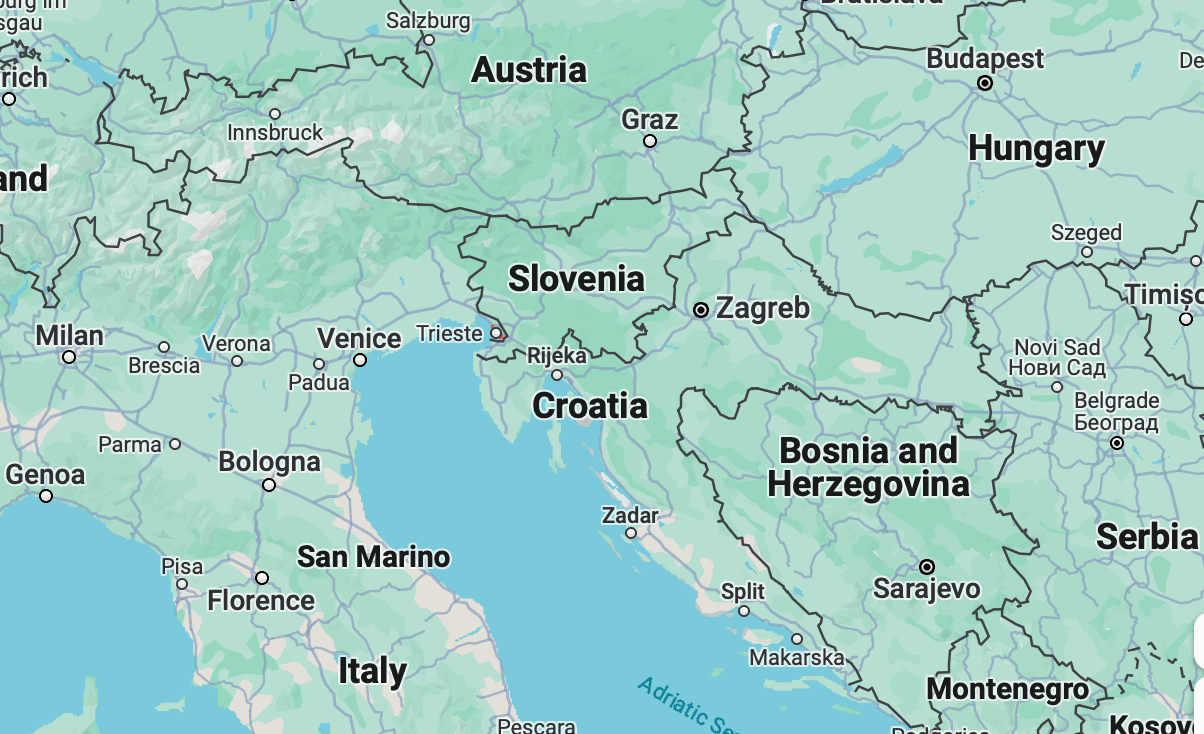

For Bojan comes from a 40,000-strong Slovenian-speaking minority in the northeastern Italian city of Trieste (one-time stomping ground of James Joyce) which knows a thing about territorial trysts.

In the 20th Century, the city went from the control of the Austro-Hungarian empire to, post the Great War, Italy. It was 'liberated' by the Germans in World War II but following the defeat of the Third Reich the area was occupied by British and US Allied forces under a UN mandate. Eventually, in 1954 the city and surrounding region was returned to Italy.

Throughout, the Slovenians within Italian borders kept their language alive - even though Mussolini's fascist regime in particular adopted a scorched-earth policy towards Slovenian culture.

Their compatriots in Slovenia were swallowed up into the new communist state of Yugoslavia before, winning independence for the state of two million people in June 1991.

LITIR AS BÉAL FEIRSTE: All last week, Bojan sent back one full page of reporting from Belfast.

Today, Slovenian enjoys strong protection in Italy. "We have our own schools from kindergarten to high school and we can study through Slovenian across the border in Slovenian universities with the guarantee that any qualifications will be fully recognised by the Italian authorities," he explains. "We can use the language in courts, in councils and all areas of life."

When he retired as editor-of-chief of Slovenian language daily Primorski Dnevnik in Trieste, Bojan decided to keep his hand in by providing occasional in-depth reports for the newspaper from European hotspots.

TRADING RULERS: Trieste sits on the Italian-Slovenian border

"We were watching the changes in Northern Ireland but decided it was worth travelling to report on the changed demographic situation and rise of Sinn Féin once government returned," he says. "So here I am."

MELTING POT: Piazza Unita d'Italia in Trieste. Pic by Fabrice Gallina. Courtesy of Italia.it

A linguist of some standing - he is fluent in Italian, Slovenian, English, Serbo-Croatian ("now two separate languages but largely the same") and Spanish and has "a basic" understanding of Catalan, German and Finnish — with a particular interest in minority languages, Bojan took time out to meeting Irish language activists during his visit.

Današnja prva stran, online na https://t.co/abOlsmaOoB pic.twitter.com/YSIfFjfWiT

— Primorski dnevnik (@primorskiD) April 18, 2024

In his 'daily letter' from Belfast this week, he has reported on the burgeoning Irish language revival. "There is impressive work going on in some places but Belfast is very much an English-speaking place so there is a lot to do," he says. "I feel that the authorities could do more to respect the heritage of the country by using bilingual signage." 40 years of reporting on linguistic rights and his prominent role in the coalition of European minority language newspapers, MIDAS, has given Bojan a special insight into the treatment of minority language communities. "Here, as elsewhere, the authorities should understand that by adding an additional language, you aren't hurting anyone - you are adding, not taking anything away."

The Slovenian speaker got a hint of the linguistic blockages though on a visit to Stormont. "I interviewed Alliance, SDLP and Sinn Féin but the DUP didn't answer my request to speak with them," he says. During his Belfast working week, Bojan visited City Hall, met language champions in An Chultúrlann, collogued with Ulster-Scots enthusiasts, visited Linda Ervine in her East Belfast Turas base and spoke with academics and church leaders.

The debate on Irish unity has consumed much of his reporting with competing views reflected daily in his dispatches. As for himself, he brings a nuanced understanding to the issue of competing identities.

"I am Slovenian," he says, "but I am also a loyal citizen of Italy. We defend our linguistic rights as Slovenians but we also respect Italians and Italian rule."

There are limits to his fealty to his Slovenian forebears though. When Italy play Slovenia at football, he admits to supporting Italy. "After all, they have a better team."

LETTER FROM BELFAST: Primorski Dnevnik on Friday 19 April.