BY the mid-19th century Belfast had become known as ‘Linenopolis’ – the centre of Ireland’s linen industry. Between 1873 and 1914, it was the biggest linen manufacturer in the world, which in turn drove its enormous population growth from 100,000 in 1850 to 385,000 by 1911. These facts appear as a remarkable story of economic and industrial success but the human cost was social decay and dehumanisation of generations of mill workers whose life’s blood and state of servitude were harnessed and exploited to make it all happen.

In 1874 there were 43 textiles mills in Belfast, the Falls and Crumlin Roads were described as resembling a “forest of tall chimneys,” such was the number of mills there. They were notorious as unhealthy and dangerous work places, paying poverty wages for exhausting working hours and employing ‘half timers’ – children as young as eight years of age. Deplorable housing and overcrowding seriously affected the health of mill-workers and their families, made worse by chronic dietary deficiency, A doctor stated at the time: “Too often the diet of the factory hands consists of tea and white bread three times daily… potatoes or beef rarely.”

Dr C.D. Purdon, Certifying Surgeon for the Belfast Factory District, published two highly influential reports, in 1873 ‘The Mortality of Flax Mill and Factory Workers Compared with Other Classes of the Community’ and in 1877 ‘Infantile Mortality Amongst the Children of Factory Workers (1864-73).’

Flax dust in the atmosphere and hot, damp temperatures were the main causes of high levels of industrial illness in the mills. Tuberculosis, asthma, bronchitis and skin diseases were all strongly associated with Belfast’s linen mills as compared with other industries. Many machine boys left the mills’ employment early on account of asthma to “go to other trades where they linger out a diseased existence.” In 1872 the average working life of operatives in the mills’ ‘preparation rooms’ (where flax dust levels were highest), before they became permanently unfit for work or died, was 17 years.

Death rates for children in their first two and a half years in Belfast in the 1860s/70s were much higher for children of mill workers compared to other occupations, outcomes were especially poor for children when both parents or widows were forced to work to earn enough to maintain their families. Expectant mothers often continued working until days before they were due to give birth, commonly returning to work within a month afterwards. Pre- and post-natal illness was common as were premature births and miscarriages. Returning to work, countless parents were forced to place their infants soon after birth “...in the care of the ‘baby-farmer,’ who feeds them on improper diet – tea and whiskey and, in order to keep them quiet, different preparations of opium.” Dr Purdon reported: “After investigating the sale of soothing syrups and different preparations of opium, the universal answer was that it was enormous and increasing.” A colleague’s profound view of the consequence of these circumstances was: “I regard the mother's return to the mill as a sentence of death upon the child.”

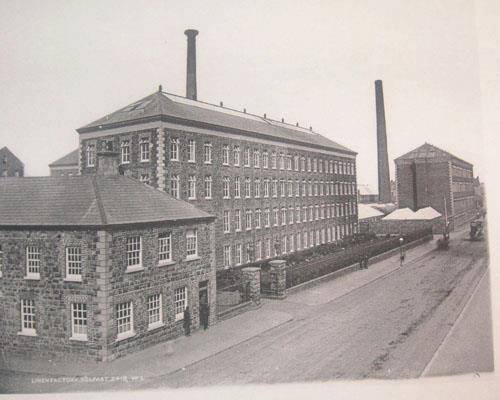

SLAVE LABOUR: Brookfield Linen Mill, Crumlin Road, early 1900s (courtesy of North and West Belfast Historical Photographical Society, National Museums, Northern Ireland)

To their taskmasters mill workers were merely ‘things’, wage labour in effect was a form of wage slavery. A clear way forward for the poor to improve their lives was through organised labour, collective action and enlightened leadership. Prior to the 1870s. Belfast’s working class had mutual support associations and sporadic strikes had occurred, but strong labour organisation through trade unions, particularly for semi-skilled or unskilled workers was absent, not least in the textile industry.

In Belfast in 1872 the Flax-Dressers’ Trade and Benevolent Trade Union (skilled male operatives) was formed. In response, the millowners formed the Linen Manufacturers’ Association. The FTBTU went on strike in 1872 for a four-shilling weekly wage increase. With 2,500 linen dressers on strike the employers adopted the tactic of a general lockout of all mill workers in Belfast until the strikers returned. It lasted a fortnight, affecting 30,000 workers, before they were forced to return on the masters’ terms with a two shilling per week increase.

A dramatic turn of events occurred on June 20, 1874, when, without warning, employers’ notices were posted up at every textile mill in Belfast stating that wages would be reduced by 10 per cent to 15 per cent from Monday, July 6. The employers claimed this was essential as there was a serious economic downturn in the textile trade. The workers believed the trade downturn was exaggerated and temporary and the sudden reduction in wages was linked to the provisions of the forthcoming Factory Act of 1874, which the employers had resisted, raising the minimum working age to nine, limiting the working day for women and young people to 10 hours and a reduced working week to 56½ hours.

The subsequent dispute over wages led to a strike commencing Monday, July 6, 1874, with 39 of 43 Belfast mills closed and over 30,000 workers on strike. Four mills remained open with no wage reductions. The Londonderry Sentinel on July 7 reported that the mill workers turned up as usual but refused to cross the gates and the strike began with unsurpassed self-confidence and determination. “The male operatives paraded a large portion of the town in processions displaying loaves on poles, black flags... The girls marched up and down the street cheering loudly and singing popular airs.”

A meeting of 5000 strikers, “of whom a great proportion were females,’’ was held later that day on the Falls Road, reaffirming their refusal of wage reductions and determination to remain on strike until their old wages were guaranteed. The speakers stressed the importance of solidarity and discipline, urging all “to throw aside their religious differences, as this was purely a matter of labour and capital.”

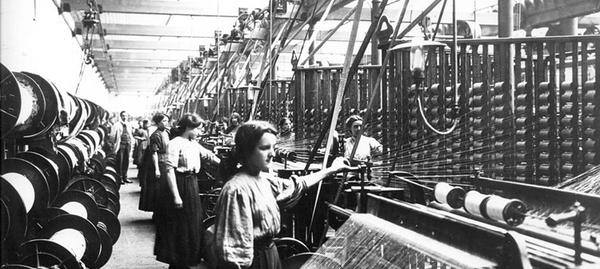

HARD WORK: Linen Mill Reelers, Belfast, early 1900s (Courtesy of Images & Memories of Old N' Ireland Pre 2000)

The unionist press were extremely alarmed at this unity of the mill workers that overcame traditional religious and political divisions, placing their class interests as paramount in a conflict between labour and capitalist mill-owners. The News Letter circulated ideas that agitators and Communists were at the head of the strike movement and most workers would wanted to work but were being intimidated to stay out.

The unionist press became more alarmed when the mill workers in Lisburn and the Glenmore Bleaching Works at Hilden, facing the same wage reductions, joined the strike. These areas were historically associated with the Orange-unionist tradition and had strong pro-British links through the Anglo-Irish landlord dynasties. The News Letter, representing the Protestant-unionist tradition, described the striking Glenmore workers as having “revolted” and being “at war” with their employers. Later, on July 22, it described strike action as akin to an “infectious disease,” revealing their deep-seated fears about the power of organised labour for uniting the working classes and overcoming traditional religious and political antagonisms.

“The contagion of ‘strike’ has spread to Lisburn and threatens to exhibit itself there in a virulent type... the symptoms are not good, and the results to the infected are likely to be very serious! Lisburn... is the capital of one of the best landed estates in Ireland, owned by one of the best landlords; is the centre of a flourishing trade; promoted by enterprising and indulgent capitalists; and ever since the Prince of Orange passed through it, en route for the Boyne, its inhabitants have been distinguished for their loyalty and their attachment to law and order. It would be a pity if anything should blacken the repute or bring disgrace upon the character of a town so famous.”

On July 17 a ‘monster meeting’ of the female mill workers on strike was held at Ross’s Field, Falls Road, with 10,000 assembled. Elizabeth Havelock addressed her sister workers: “...the female workers of Belfast would not accept the reduced rate of wages... They had all only once to live and once to die, and the question was whether would they would die now with the reduced wages or without it... There was a very good demand for trade at the present time, notwithstanding what might be told to them to the contrary; and therefore, she called on all women... to say to the mill owners, ‘Die dog, or eat the hatchet.’”

Mary Browne followed. “No-one knew what the work of a mill worker was but a mill worker herself – how they left their employment at night with their clothes drenched to their skin with sweat... They had made fortunes for the mill-owners... while they were themselves poor, ignorant and unlearned slaves.”

EXPLOITED: Linen mill early 1900s (Belfast Images and memories)

Workers’ representative John Brownlee announced they now saw “the necessity for an organisation of the working classes of this country, but when next the occasion occurred the employers would find one the power of which they could never anticipate.”

Two meetings with employers and delegations representing the mill workers occurred in July – that of the Flax Dressers’ Union, and later representatives from the three religious denominations. Both came to nothing. On Friday, July 31 the Belfast mill owners made known their intention to open their mills on Monday, August 3 at 6am under the following pre-conditions: “This concern will resume work on Monday morning next, the 3rd of August, at the reduced wages; but in the event of any class of workers not coming in, or if work be not resumed in all the mills and factories now standing idle, this concern will be closed on one day’s notice, and wages paid only to the date of closing.”

The mill operatives appeared unanimous in their resolve to continue with their strike until they were guaranteed their old wage rates, despite the worsening hardships and the seriously depleted strikers’ relief fund, whilst the employers seemed prepared to starve the strikers into submission. On August 11 the Ulster Examiner and Northern Star, supporting the mill-workers, summed up the ominous reality of the situation: “The employers, whose salaries are not stopped during the strike, can hold out indefinitely... The operatives may be starved into submission; but this is not the rule by which to judge the present struggle. Physical necessity... may eventually compel them to resume work, but undoubtedly the moral victory will be with the side that is compelled through physical necessity to give in.”

On August 26, after a meeting, a final agreement was reached between employers and strikers, which brought the strike to an end; the official statement said: “We have pleasure in stating that the difference between them was ‘amicably adjusted’. Various specialist sections of workers accepted a 5-8 per cent reduction in wages. Given their bottom-line position during an arduous seven-week strike, despite their courage, it’s difficult to see the outcome as other than a defeat for the mill workers. The resources, wealth and power of the industrialists had overwhelmed the impoverished, suffering and exhausted strikers.

Despite this, it was clearly of enormous significance for Irish labour history, for it was the first general strike in Belfast’s industrial history that involved all sectors of one industry: doffers, weavers, spinners, preparers and others, and largely female operatives. John Brownlee described the strike as “the greatest agitation that had ever existed in Belfast up to the present time.”

Flax St Mill, Ardoyne (Courtesy of North & West Belfast Historical Photographical Society)

Sadly, the deplorable sanitary and housing conditions, poverty wages, appalling working conditions and poor occupational health outcomes of the mill workers remained well into the 20th century. By 1891, nearly half the linen mill workers who died in Belfast were suffering from tuberculosis, and 90 per cent of them were under 40 years of age. Trade unionism in the Belfast linen industry by the end of the 19th century was weak and divided. By 1900 out of 65,000 millworkers there were only 5000, (9 per cent), belonging to nine different unions.

In 1913, James Connolly said that North-East Ulster “Being the most developed industrially, ought to be the quarter in which class lines... should be the most pronounced and class rebellion the most common. As a cold matter of fact, it is the happy hunting ground of the slave-driver and the home of the least rebellious slaves in the industrial world.”

Brendan Muldoon©2022