I WAS in Belfast city centre last week for the first time in three months. I was to meet a 'returned Yank', a man who has returned to these parts after nearly sixty years in USA. I was told he had two hours to spare.

We took a walk through the city centre. In High Street I thought it might be a good idea to explore the entries. When I pointed out the statue of Henry Joy McCracken he asked: “Was he black?”

Later, towards the end of our two hours, I showed him the statue of ‘the Black Man’. His response was, “He's not black, he's green.”

On my way home I chuckled at my brother’s observations – anything which doesn't pertain to the USA is irrelevant. I won't repeat his comments on Presbyterians except to say that for him religion is “none of his business.”

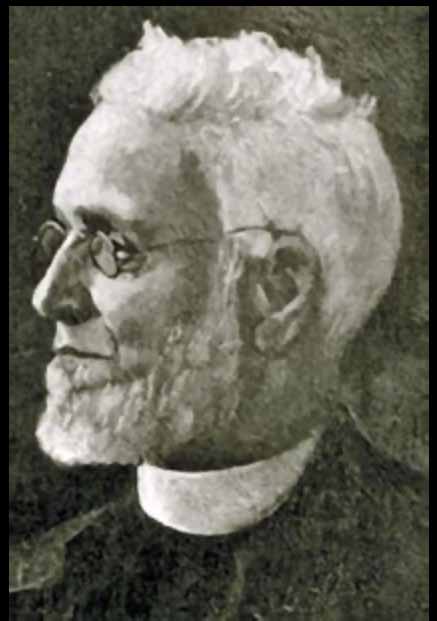

I often reflect on what might have been but for the actions of Reverend Henry Cooke. While I regard him as the main founder of sectarianism in the north of Ireland, there have been a number of north of Ireland Presbyterians who gave of their best for Ireland. One such man, now largely forgotten, was Reverend James Brown Armour from Ballymoney. Born just outside the town in 1841 he was the youngest son of a small tenant farmer. He studied law but was persuaded by his father and older brother on their deathbeds to become a minister. He took up duty in Ballymoney in 1869. He was a member of the Liberal Party and was prominent in agitating for land reform. He worked for the rights of the tenant farmer and in a speech in 1873 he said: “We want the principles of even-handed justice to rule in the north, south, east and west of Ireland with the restitution of these rights which agents, with the magnanimity and persistence of mice, have been nibbling away for the last two hundred years.”

He led the Route Tenants’ Defence Association (the Ballymoney district was known as the Route) and also proposed the establishment of a Catholic University. When Gladstone proposed Home Rule for Ireland in 1886 he was initially opposed to it but soon became convinced that it was the best way forward.

NOT EASY BEING GREEN: The statue of the Black Man in Belfast city centre

It would not only boost the Irish economy, but also bring reconciliation between Protestants and Roman Catholics. When the second Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1892 he asked the Presbyterian General Assembly to support it. He was largely sidelined but continued to advance Home Rule at every opportunity. He taught in Magee College Derry, travelling by train several times a week. Among the lecturers was his cousin, Reverend James Brown Dougherty, a native of Garvagh. Dougherty moved in Dublin circles and had Armour appointed as a chaplain in 1908. This gave Armour contact with Lord Aberdeen, a Liberal under secretary in Dublin Castle. He used his influence to have a shirt factory owner made a lieutenant in Derry. In turn his public office helped him to defeat the Irish Unionist in Derry in the 1912 election. When he died less than two years later Dougherty again won the seat for the Liberals. Eoin McNeill gained the same seat for Sinn Fein in 1918.

Sir Edward Carson rallied the Ulster Unionists to oppose Home Rule and in September 1912 when he encouraged up to half a million to sign the Ulster Covenant opposing Home Rule.

In October 1913 Armour organised a meeting in Ballymoney Town Hall attended by 500 Protestants (no Catholics were invited) He, Roger Casement and Captain Jack White from Broughshane, who later helped James Connolly found the Irish Citizen Army, addressed the crowd. Armour denounced Carson as “a sheer mountebank and the greatest enemy of Protestantism”. He later wrote that Carson should be tarred and feathered.

“We, the undersigned, Ulster Protestant men and women over the age of 16 years, hereby repudiate the claim of Sir Edward Carson to represent the United Protestant opinion of Ulster, reject the doctrine of armed resistance to the legitimate decrees of Parliament; and declare our abhorrence of the attempt to revive ancient bigotries and dying habits in this Province.”

ClassicPenguinCovers#394 Cover sketch of Sir Edward Carson by 'Lib' from Vanity Fair on this 1961 copy of 'Six great advocates' by Lord Birkett pic.twitter.com/VwgGPVX6Os

— Edinburgh Books (@EdinburghBooks) January 27, 2018

That's the opening paragraph of an ‘Alternative Covenant’, or the Armour Declaration, signed by 12,000 Protestants and published in 1913.

The reference to “ancient bigotries and dying habits” is interesting, it showed that over a hundred years ago thousands of Protestants welcomed the fact, as they then believed it to be, that any lingering sense of hostility that existed between Protestants and Catholics could be seen as a flicker from a fading past.

Roger Casement spoke at the meeting and talked of setting the “Antrim Hills alight.” Unfortunately it didn’t happen.

Although he and Casement went separate ways, Armour continued to oppose Home Rule and spoke out against Lloyd George in 1920.

He died in 1928 and on the morning of his funeral the bells of the Church of Our Lady and St Patrick, the local Catholic church, rang out, demonstrating the esteem in which he was held by all in the town and surrounding districts.